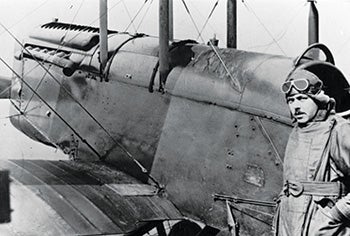

Jack Knight’s was not a hero’s face. Neither rugged nor square-jawed, it was, rather, overly broad in the forehead and narrow in the chin, somewhat like Fred Astaire’s or the famous face on the bridge in the Edvard Munch painting called The Scream. But heroes are as heroes do.

Knight was an airmail pilot at the very start of airmail, years before Charles Lindbergh was. President Warren Harding wanted to shut down the airmail, deeming it unduly dangerous and costly, unreliable and not even especially swift, since mail was flown only by day and loaded onto trains at night. The assistant postmaster general in charge of the airmail, Otto Praeger, in a bid to deflect the presidential ax, set out to demonstrate that mail could be flown through the night.

On Feb. 22, 1921, the night of a full moon, four de Havilland DH-4s took off at dawn, two from New York and two from San Francisco. One crashed in Nevada, killing the pilot. Two westbound airplanes gave up in the face of a snowstorm near Chicago. At evening, one lot of eastbound mail had been delivered by Knight to Omaha, Nebraska. Bad weather lay ahead, with snow still falling between Omaha and Chicago, and the pilot who was to fly the next leg declined to continue. Jack Knight took off instead and flew through the night, freezing cold in his open cockpit and guided by bonfires lit by postal employees and by farmers. He refueled at Iowa City, remarking later with some understatement, “Say, if you ever want to worry your head, just try to find Iowa City on a dark night with a good snow and fog hanging around.” By morning he had reached Chicago, where another airplane took his cargo and continued to the East Coast, completing the transcontinental trip in 33 hours.

Knight had no radio. He navigated by a combination of dead reckoning and pilotage. Pilotage means navigating by visible landmarks; in the Midwestern night before rural electrification, few of those were to be found. Dead reckoning means calculating your location from time, speed and direction of travel. With dead reckoning, here was seldom exact, but it was good enough that Lindbergh made his landfall in Ireland, after 20 hours over water, where he expected to, and countless others after him had the same experience. When I flew the Atlantic in pre-GPS 1975, a ferry pilot told me simply to set the compass needle at E, for “Europe” — dead reckoning in a tiny nutshell.

In principle, you would dead-reckon from one unmistakable landmark to another; but alas, from time to time the landmark would not appear, and that would “worry your head.” You would get the tense, creepy feeling of being lost in the sky. It was different from being lost on the ground; in the sky, there was a deadline set by fuel. No one liked the feeling, but still, it had a value: It reminded you that what you were doing was dangerous.

The night mail officially began operations in 1924. To provide its pilots the landmarks that the countryside begrudged them, the Postal Service set up the first airway system. It was defined by electric beacon lights; Jack Knight helped lay them out. At one time 1,500 beacons marked 18,000 miles of airways. I followed them across Arizona in a 175 in the ’60s, but by that time the system was being dismantled. There was something sweet and warm in a beacon winking at you from a distant mountaintop, something missing in the chill abstraction of a radio signal. The only remnant of the beacon airways today is a string of 17 lights in the mountains of western Montana, maintained by the state. Try it, if you’re up there; you’ll see what I mean.

The beacon lights were supplanted by four-course “Adcock ranges.” Always a little out of step with the times, I carefully studied four-course range procedures before taking my instrument tests, but the four-course ranges were also on their way out and neither the written nor the practical test made any reference to them. A few years ago I searched through a box of old charts for a four-course range; the only one I found was in Chihuahua, Mexico, on the south half of a 1969 El Paso sectional (which is still in perfect condition, by the way — they used good paper).

Four-course ranges were low-frequency beacons like NDBs, usually located near airports, and set up to broadcast in four lobes roughly corresponding to the quadrants of a circle. In one lobe and the one opposite it, the signal was the Morse letter A, dot-dash; the other two were dash-dot, N. Within the narrow “courses” where the lobes overlapped you heard a continuous tone; one or more of these would guide you to a runway. To make an instrument approach, you first flew to the beacon by dead reckoning. Then you oriented yourself by some turns intended to tell you, as the audio signal grew louder or fainter, which of the two A or N quadrants you were in. Finally, you flew out along the appropriate course, made a procedure turn, and began your descent inbound. Pilots found that they could fly more precise approaches by placing themselves on the edge of a course, where the A or N just started to emerge from the background drone.

As you may imagine, to fly a range approach in icy weather in a DC-3 required a firm grip on oneself and a well-developed ability to transform random and obscure symbols into a mental map of the world and where you were in it. Underlying that map was our old friend dead reckoning. Besides calculating speed, time, distance and drift over long distances, dead reckoning also meant maintaining situational awareness on a local scale. Pilots constructed a mental model of their position and continually updated it, so that the four-course range was not just a bewildering arrangement of dots and dashes but an inner space in which an imaginary airplane, felt rather than seen, crept along. I think the difference between people who had the makings of pilots and those who didn’t must have been more marked then than it is today.

GPS, and the digital processing it makes possible, has changed all that. A drug seductive to even the fiercest Luddite, GPS makes skill, knowledge and intuition obsolete. It makes us at once infants and gods. Observer and observed, we watch from on high as our icon, a digital metaphor of self-awareness, creeps across the map. With GPS, there is no longer such a thing as “lost.” Navigation, a great and noble art whose traditions stretch back into prehistory, has been replaced by a computer game. Its tools, the products of so much experience, ingenuity and self-sacrifice, will soon become curiosities; its methods and skills, so recently separating life and death, will eventually be forgotten.

Jack Knight’s night flight — it will soon be a hundred years ago — must be, to new pilots who have trained in the era of GPS, all but unimaginable. His airplane, a two-place biplane designed during the First World War and modified to replace the front cockpit with a hold for 400 pounds of mail, could do 100 knots or so and stay aloft for nearly four hours. The cold, the darkness, the din of the 400 hp Liberty engine far out in front and the endless peering into darkness unrewarded for long periods by any answering light — these were trials to which we modern pilots, snug and cozy in airtight cockpits and ministered to by a crew of digital assistants, are strangers. We are much better off, but we have also forfeited something: an adventurous life in which anxiety and relief alternated like the beating of a heart. Beryl Markham, one of the pilots of that rash and risky era, foresaw what was to come, and in her autobiographical West with the Night she wrote of the future we now inhabit:

- _By then men will have forgotten how to fly; they will be passengers on machines whose conductors are carefully promoted to a familiarity with labeled buttons, and in whose minds the knowledge of the sky and the wind and the way of the weather will be as extraneous as passing fiction. _

Get online content like this delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for our free enewsletter.

We welcome your comments on flyingmag.com. In order to maintain a respectful environment, we ask that all comments be on-topic, respectful and spam-free. All comments made here are public and may be republished by Flying.