When I was a kid, my Uncle Dennis recognized my aviation obsession and began feeding it with a steady stream of books. He would visit from New York on holidays and handoff the latest aircraft encyclopedia or a decades-old, out-of-print aviation reference guide packed with history, photos, and specifications.

One included a section about the North American XB-70 Valkyrie, a nuclear strike bomber prototype designed in the 1950s to fly long distances at Mach 3above 70,000 feet. I considered it the ultimate aircraft, and when I read that the single surviving example lives in the Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, along with other rarities like the Convair B-58 Hustler, I committed to a visit.

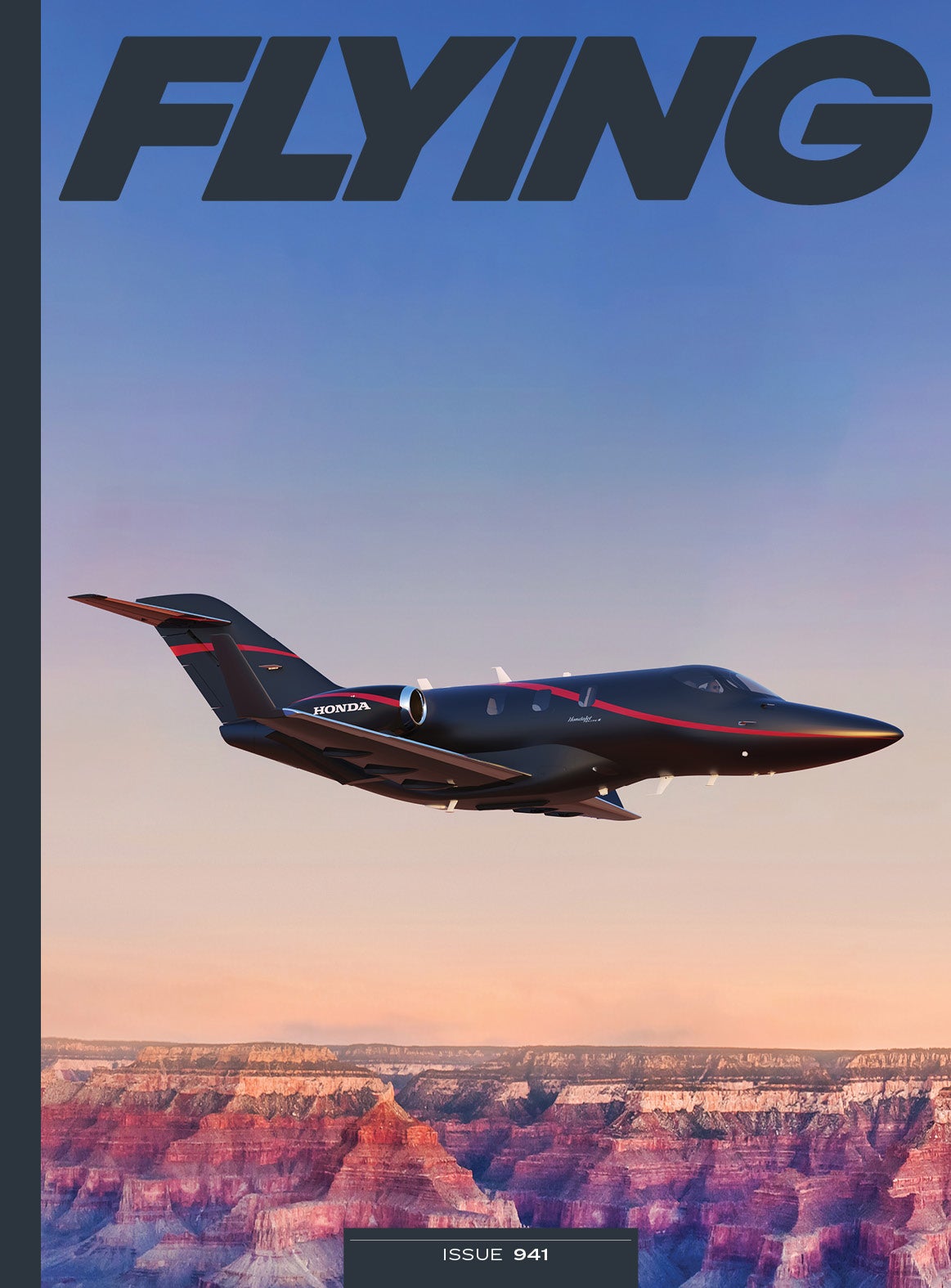

If you’re not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Decades later, my wife and I were leafing through real estate listings when we came across a lovely Queen Anne house labeled as the “steal of the week,” located in Dayton. This was around the 100th anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight, and the city was enjoying an uptick in national attention.

The experience reminded me that I had yet to visit the museum or other attractions in town—and rekindled my interest in making the trip.

Getting There

It took a while, but I recently loaded the Commander114B and took off toward Dayton, which has gained steadily in appeal as a destination in recent years, especially for aviation fans. We flew first to Dayton/Wright Brothers Airport (KMGY), where a small museum houses a collection of artifacts linked to the Wrights and the earliest days of controlled, heavier-than-air flight.

It made sense to stop at the museum first because it is open for just a few hours on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The non-towered airport also provided a good place to collect my thoughts before plunging into the busy airspace around Dayton International (KDAY) and Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

The museum’s main attraction is a replica of the Wright Model B aircraft developed several years after the famous 1903 Wright Flyer. The B illustrates how aircraft design changed as early aviators, self-taught and dependent on trial and error, gradually figured out what worked best.

For example, the two-seat B has wheels—an obvious advantage over its predecessors. Its elevator sections are mounted on its tail instead of forward-mounted, as on earlier models. In short, it looks more like today’s image of an airplane.

Soon I headed for the Air Force museum, a much larger, busier place with an airport environment to match. The museum is next to Wright-Patterson, which is next to Dayton International. For a pilot accustomed to largely non-towered airports within northern New Jersey, upstate New York, and New England, the notion of taking off from Wright Brothers and immediately calling Columbus Approach—because I was already crossing the 20-mile mark—seemed daunting. The radio traffic was so thick that I had to circle before I could reach the controller.

I felt more secure after receiving a squawk code, but the radio never quieted down, and that distracted me just enough to mistake the Air Force base for my destination. You might think the row of C-17 transports parked on the ramp would have given it away, but no. Lucky for me the controller was patient and assured me that if I looked to my left I would see that I was indeed on a left base for 24L at Dayton. The 7,285-foot runway helped mask the excess speed I carried to touchdown, and the long taxi to the FBO, Wright Brothers Aero, was uneventful (the Wright name pops up often in Dayton). I asked the ground controller for a progressive, but it was an easy straight shot on Charlie. Everything worked out fine.

Worth the Wait

In about 15 minutes after topping off, I was walking into the Air Force museum—something I had looked forward to for decades. Though I missed out on the experience as a child, that did not seem to matter because I immediately felt like a fourth-grader upon entry. I had not felt that thrillingly overwhelmed tingle since my first day at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum in 1976. Back then I wanted to run from one end of the place to the other in order to see everything before closing time.

It can take several days to see everything in a museum like this, and since I had only hours, I had to work from a short list of must-see items that included the Convair’s B-36 Peacemaker, Boeing’s B-47 Stratojet and B-52 Stratofortress, and the aforementioned B-58 and XB-70. While I would have taken the 450-nautical mile trip just to see the Valkyrie, I was treated to an immersive look at the evolution of military aviation, from the earliest kite-like aircraft that Wright, Curtiss, and other manufacturers first sold to the armed services to the stealthy F-22 Raptor.

I like being able to get close to the aircraft, and the folks at the museum seemed to understand this need. Looking up into the bomb bays and wheel wells of antique airplanes is a rare treat. Walking underneath the XB-70 gave me an appreciation not only for its size but for the smoothness of its beautifully crafted parts. It is a breathtaking machine with an impressively smooth finish to it. While I was almost always close enough to touch the exhibits, museum staff appeared to trust that I would only look.

The Air Force museum’s collection is vast and varied. The exhibits unfold in chronological order, which helped to mitigate my concerns about possibly missing something. But as I looked for items on my mental list I was continuously drawn to aircraft I knew only from photos or simply had never seen, like the Curtiss O-52 Owl. The Owl had a high, strut-braced wing, radial engine, and main landing gear that retracted into the fuselage, leaving the wheels and tires partially exposed. It looked like the offspring of a Grumman Wildcat fighter and a Piper J-3 Cub. Another surprise was the fleet of presidential aircraft, including Independence, the DouglasVC-118 that carried Harry S. Truman. It is a military version of the DC-6 airliner. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Columbine, a Lockheed VC-121E that you might call a Super Constellation, is also on display. So is the Boeing VC-137C, or 707, that transported eight sitting presidents over 36 years before a modified 747 replaced it.

Topping off the experience, visitors can walk through the presidential airplanes and see their interiors through acrylic glass. I had a wonderful time comparing the interior decor of the piston aircraft with the later 707 version of Air Force One. They all seem rather modest next to modern business-jet cabins.

Other Attractions

As with many smaller cities across the U.S. that are revamping their images, there is plenty to do in Dayton, from exploring the life and work of poet and author Paul Laurence Dunbar, another famous Daytonian, to visiting galleries, entertainment venues and a variety of restaurants, or taking in Minor League baseball games. America’s Packard Museum is a worthwhile stop for anyone interested in the development of automobile transportation.

There is also more aviation history to explore in places like the John W. Berry, Sr. Wright Brothers National Museum, National Aviation Hall of Fame, and the National Aviation Heritage Area, which includes the building that housed the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop. The buildings that housed the Wrights’ original airplane factory were damaged in a fire that broke out during my visit to Dayton. Preservation and city officials are assessing the damage and looking at options for the factory complex, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Visitors to Dayton can also tour Hawthorn Hill, the mansion where Orville Wright lived following his success in aviation. The house is sometimes called the “first pilot’s last home.” And this might be cheating, but a 20-minute drive north of town will get you to the Waco Air Museum, which celebrated 100 years of the aircraft company September 15 to 17.

I felt a bit sad leaving Dayton when I knew there was more to see, but the trip home turned out to be another highlight. After delays for rain storms and low ceilings, I flew back to New Jersey in ideal sunny and clear conditions. I also received on-the-job training in talking with ATC as the Dayton Tower switched me to Columbus Approach, who handed me off to Indy Center. From there, I talked with Cleveland Center, Pittsburgh Approach, Johnstown, Harrisburg, Wilkes-Barre, and New York, before being released to my home airport in Sussex, New Jersey (KFWN).

By the halfway point, I felt comfortable with the rhythm of radio calls and began to enjoy the back-and-forth. I no longer worried about possibly saying the wrong thing on the air. All that practice also wiped away any apprehension I might have felt about calling New York Approach out of the blue or requesting clearance through any Class B airspace I happen to encounter.

Airborne excursions will be easier from now on.