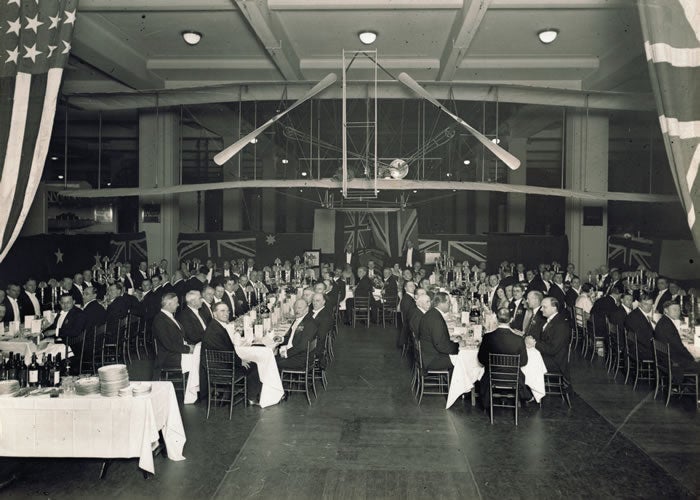

In the shadow of the original Wright Flyer, at 9:15 p.m. on May 30, 1935, in London, England, Donald Wills Douglas delivered the 23rd Wilbur Wright Memorial Lecture—so named for one of the brothers who had successfully launched powered, controlled, piloted flight nearly 32 years earlier.

How the Flyer came to hang in what is now the Science Museum for 20 years is a fascinating story all its own—it was placed there by Orville Wright in 1928 during his ongoing feud with the Smithsonian Institution in the U.S. The Flyer was only given to the Smithsonian in 1948 following Orville’s death.

Douglas had been invited to speak to the Royal Aeronautical Society in this honored way because of the growing fleet of Douglas DC-2s—the “bi-motored” air transport that would fulfill the promise of viable commercial passenger air service.

He had more concepts for the future in mind, too, predicting the advances in autopilots and “radio beams” for navigation. Douglas even foresaw an unmanned aerial vehicle piloted remotely into London using those very beams during the city’s famous bouts with fog.

But he would solidify his company’s future with the incremental advances that came next.

First, the DC-1, then the DC-2

Douglas Aircraft Company (DAC) had already flown the first of the Douglas Commercial line, the DC-1, on June 22, 1933, at Clover Field, in Santa Monica, California—now the site of the Santa Monica Municipal Airport. Only one was built, though, because the company immediately went into production on an improved version, the DC-2.

The DC-2 featured a cabin stretched by three feet so that it could hold 14 passengers—and a co-pilot’s instrument panel, an updated landing gear system, and hydraulic brakes. DAC had manufactured 66 DC-2s by the time Douglas spoke to the August gathering in London in the summer of 1935.

The DC-2 had set a transcontinental speed record in March 1935, in a west-to-east run that clocked only 12 hours and 44 minutes—a giant leap at the time, and a great competitive advantage for Transcontinental & Western Air, the predecessor to Trans World Airlines, or TWA.

United Airlines had partnered with Boeing on its 247, which first flew in February 1933. Even the DC-2 was a vast improvement to the Boeing air transport. For one, the wing spar didn’t require stepping over in the main cabin.

Douglas saw the challenge clearly.

Enter the DST

It took a phone call from American Airlines’ C.R. Smith to affirm he wasn’t mad to keep growing the popular DC-2. Douglas already had in mind the next step up in size for what he imagined was an evolutionary series of air transports to circle the globe.

That phone call in which Smith placed an order for Douglas Sleeper Transports (DSTs) was followed by a telegram on July 8, 1935, confirming the deal. He’d buy 10 of the 20 airplanes for $795,000.

That infusion helped leverage DAC’s further investment in the DC series, along with significant engineering development produced by the Northrop division of the company. The collaboration with American’s engineering team also supported the effort.

By the time December rolled around, the DST was ready to fly.

A Routine Afternoon Flight

A cool, clear day dawned in Santa Monica on December 17, and the final configuration of the DST had been settled. This was the sleeper version—the day version would be known as the straight DC-3.

Though there had been a lot of fanfare for the first flight of the DC-1, there was little surrounding the initial aerial test of its progeny. Test pilot (and sales lead) Carl Cover settled into the left seat around 3 o’clock in the afternoon, joined by co-pilot Frank Collbohm. His logbook entry made it appear as though he’d just tested another DC-2 off the production line—in fact, the pair had performed a test flight that morning on a DC-2 that DAC had prepared for delivery.

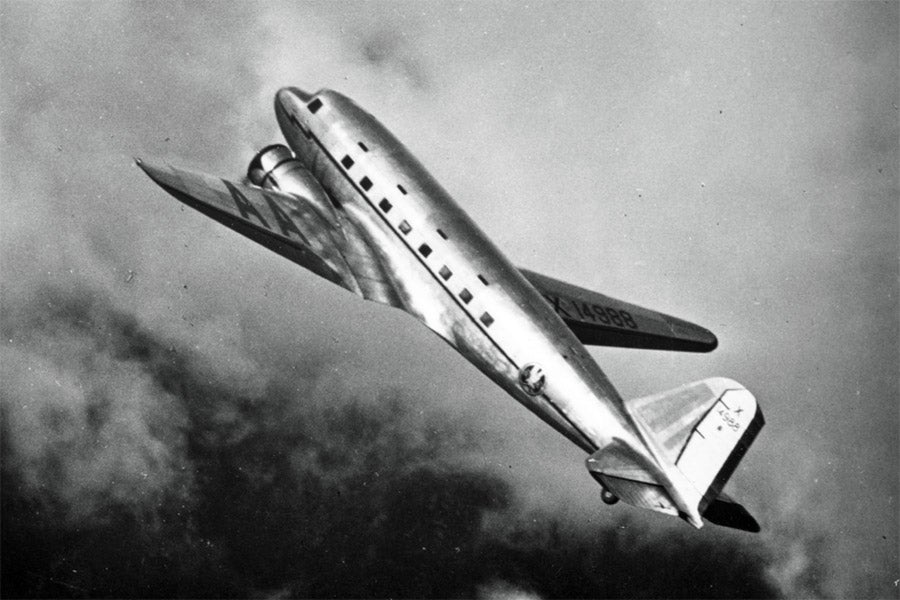

There were few large leaps in the aircraft’s design between the models—a larger cabin to hold the 28 seats or 14 berths, and upgraded engines to the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasps or the Wright R-1820 Cyclones that were slung on NX14988, the registration on that first DST they flew that day.

After an hour and a half, the DST that would become American’s Flagship Texas touched down on the runway (since realigned to 21/03), completing a routine flight that would later mark the airplane’s place in history.

It just happened to be 32 years to the day after the Wrights first took flight.

Editor’s note: Information for the story drawn from “DC-3: An Aircraft for the Ages,” Together We Fly: Voices From the DC-3, and Honest Vision: The Donald Douglas Story, published by ASA.