Eugene Corbett Patterson died last January. You may have a flicker of name recognition, as his obituary was in almost every newspaper in the country. The New York Times announced his death on the front page and devoted considerable space to this farm boy, soldier, scholar, journalist and editor. To me, he was the best copilot I ever had. More than that, he was a mentor and friend who showed me how to live and, in the end, how to live life out.

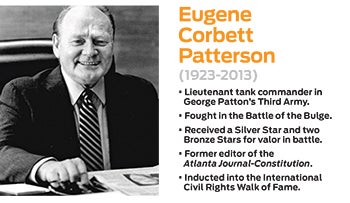

Gene Patterson was a lieutenant tank commander in George Patton’s Third Army. He fought in the Battle of the Bulge. He was awarded a Silver Star and two Bronze Stars for valor in the battlefield. That wasn’t the half of it.

From General Patton he learned two important lessons. First, “Good generals make plans to fit the circumstances; bad generals try to make the circumstances fit their plans.” These words can equally be applied to pilots in command. And, second, “Never take counsel of your fears.”

Thus emotionally armed, Patterson served as an Army aviator after he survived World War II. In Texas he flew Stearman biplanes. He used this airplane to sort through possible female company made available by a local Army hospital. “The nurses who squealed with delight during stalls and spins were generally good dates,” he once told me. “The ones who cried and hid their heads in their hands weren’t so good.”

Sensing that an Army career could be backed up for years due to the postwar glut of officers, Gene took his leave. Mustered out in Texas, he went to the nearest town and got a job at the local newspaper. The South would never be the same.

After working for the United Press in New York and London, in the 1960s Patterson became the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, where he wrote a column every day for eight years. He stood tall against the segregationists and for the common man. He told me that after Patton, the Atlanta bomb threats and the shooting of his dog were small potatoes in comparison.

When a church bombing in Birmingham left four young girls dead, Patterson wrote: “Let us not lay the blame on some brutal fool who didn’t know any better. We know better. We created the day. We bear the judgment. May God have mercy on the poor South that has been so led.” Walter Cronkite had him read the entire piece on the national news (only 15 minutes in those days), and the Pulitzer Prize soon followed.

I knew none of this when I met Gene Patterson. I just knew that he liked airplanes, seemed to have a strong moral compass and wrote like an angel. I was drawn to him in an instant. That was 30 years ago.

When I approached him and said I’d like to write, he said, “Well, write something.” When I handed him 800 words in a sealed envelope, I had no idea how my life was going to change for the better. You wouldn’t be reading this if it were not for Gene Patterson, and I would not have the privilege to submit a monthly column to Flying magazine, that most venerable of titles.

With Gene, my wife, Cathy, and another couple, we carried out several escapades. Gene always flew right seat in our Cheyenne. I always learned something from each flight. When we flew from Tampa to Savannah, Georgia, with lots of thunderstorm activity about, Gene marveled at the courteous tone of both pilots and controllers. There were heading requests by frazzled crews and several “direct to destination when able” replies from Jacksonville Center’s cadre of experienced storm-avoidance experts. Once we were on the ground and at the bar, Gene called the cadence he heard on the frequencies “civil music.” I have thought of it as just that ever since.

On one trip to Charleston, Gene and I knew that we had a balky flight director. Without warning the command bars would lurch upward, which was no big deal when hand-flying, but posed a certain excitement when on the autopilot. Sure enough, soon after we leveled off, the champagne hit the ceiling in the back while Gene and I laughed.

When landing at Naples, Florida, I flared too soon, dropped the nose just a little, feared hitting the nose wheel first, pulled back again and repeated the entire dance for what seemed the entire length of the pavement. “Hey Dick, that sure was a wavy runway,” Gene congratulated me.

But it was a flight from New Orleans to Tampa soon after 9/11 that set the bar. I had taken the plane to KMSY for a two-day visit at the surgery department at the Ochsner Clinic. Cathy and Gene and another couple were to airline to New Orleans on a Saturday morning and ride home in Cheyenne comfort on Sunday. Fearful of the long lines common after the 9/11 disasters, they all arrived at the airport with ridiculous time to spare, only to find that the bar had a two-for-one offer before 8 a.m. Apparently, this could not be passed up. When I caught up with the revelers around noon, it was clear that they were just getting started. The ensuing 28 hours were said to cause damage second only to Katrina. I went to bed early; I couldn’t keep up.

The next morning, a hurricane was bearing down on Tampa and I wanted to get going. It was not an easy crowd to wake up. We had virtually no weather until the last 10 minutes of the flight. Gene wrote wonderful thank-you notes, and I have kept this one from that trip: “As you know, Joyce paid my way on Southwest and you paid my way back on Air Karl, so I feel I’ve enjoyed the cheapest transportation. More important, I got to fly co-pilot to a basically unemployed captain who keyed a few numbers in the autopilot and drank coffee.”

Gene took great interest in my learning the Learjet, though he was worried that a guy my age couldn’t keep up with the speeds. After reading a draft of a column about my first revenue flight as a first officer for Elite Air in St. Petersburg, Florida, on a Lear 31A, he wrote me a treasured letter.

“I remember years back when you told me you’d like to fly jets and I cautioned you about reflexes at your age. So you wait until you’re 66 to clock V1 and rotate wearing three bars. Damn.” Who wouldn’t want a mentor who wrote such laudatory missives and believed in you?

The day before he died, Gene sat up in his bed and asked me with focused interest how an ancient Learjet could crash in Mexico with a popular singer and an octogenarian captain on board. With less than 24 hours to go, he was still into airplanes.

Gene Patterson’s funeral service in St. Petersburg was a pageant. I found myself as one of three eulogists — the other two were famous newspapermen known for their way with words. Phil Gailey, a retired editorial-page editor at the St. Petersburg Times, said, “I will remember Gene Patterson as a mighty man who loved everything that is precious and fragile in this world. He had no use for the hard souls among us.”

Howell Raines, formerly editor of the New York Times, said, “It is a daunting task to sum up this great American life in one eulogy, even if it could be an hour long, rather than the five minutes Gene, ever the editor, prescribed. As you all know, he was a man of many parts: farm boy, soldier, scholar, journalist, bon vivant, singer of hymns, raconteur, passionate, if not particularly lucky, fisherman.”

As you can imagine, I was petrified to speak, sandwiched between such eloquence. I went back to a favorite passage of mine from St. Exupery, that airmail poet of the early days of aviation. Writing about pilot friends who died in then all-too-common airplane accidents, he wrote, “Bit by bit it comes over us that we shall never again hear the laughter of our friend, that this garden is locked against us. And at that moment comes our true mourning, which, though it may not be rending, is yet a little bitter. For nothing, in truth, can replace that companion. Old friends cannot be created out of hand. It is idle, having planted an acorn in the morning, to expect that afternoon to sit in the shade of the oak.”

We buried Gene in Arlington in March. It was a clear day, and Reagan National was operating to the north. As the Army band serenaded us with what my father called “shipping over music” and the horse-drawn carriage made its way to the Patterson grave, I watched with emotion the steady stream of sunlit shiny airliners as they strained for the sky. It seemed fitting.