Sometimes we face situations as pilots that we feel lucky to walk away from. In my case, I learned a valuable lesson in dealing with hazardous attitudes and forgoing a checkout on a similar airplane to the one I had been flying. Little did I know that this situation would become the catalyst for my future career decisions, as well as offer me valuable perspective as a part-time CFI that I now share with my students and colleagues.

It was a cold winter evening in February 2007. I was still a pretty fresh private pilot who was just getting ready to begin training for my instrument rating. To my surprise, the flight school owner called and asked if I wanted some free flying. I tried to temper my excitement at the thought of not having to pay for flight time, but alas, I responded with an enthusiastic “Absolutely!” In no time, I was on my way to the airport. Earlier in the evening, an instructor and his student landed at Lagrange Airport, approximately 30 nautical miles away. When they were preparing to leave, the aircraft would not start. The flight school owner explained that he needed someone to go pick them up as soon as possible. The only airplane available was a new-to-us 1973 Piper Cherokee 180, in which I had not had a checkout. Being that I had done all of my primary training in a Piper Warrior, the owner said I would be fine and gave me his blessing to do the flight.

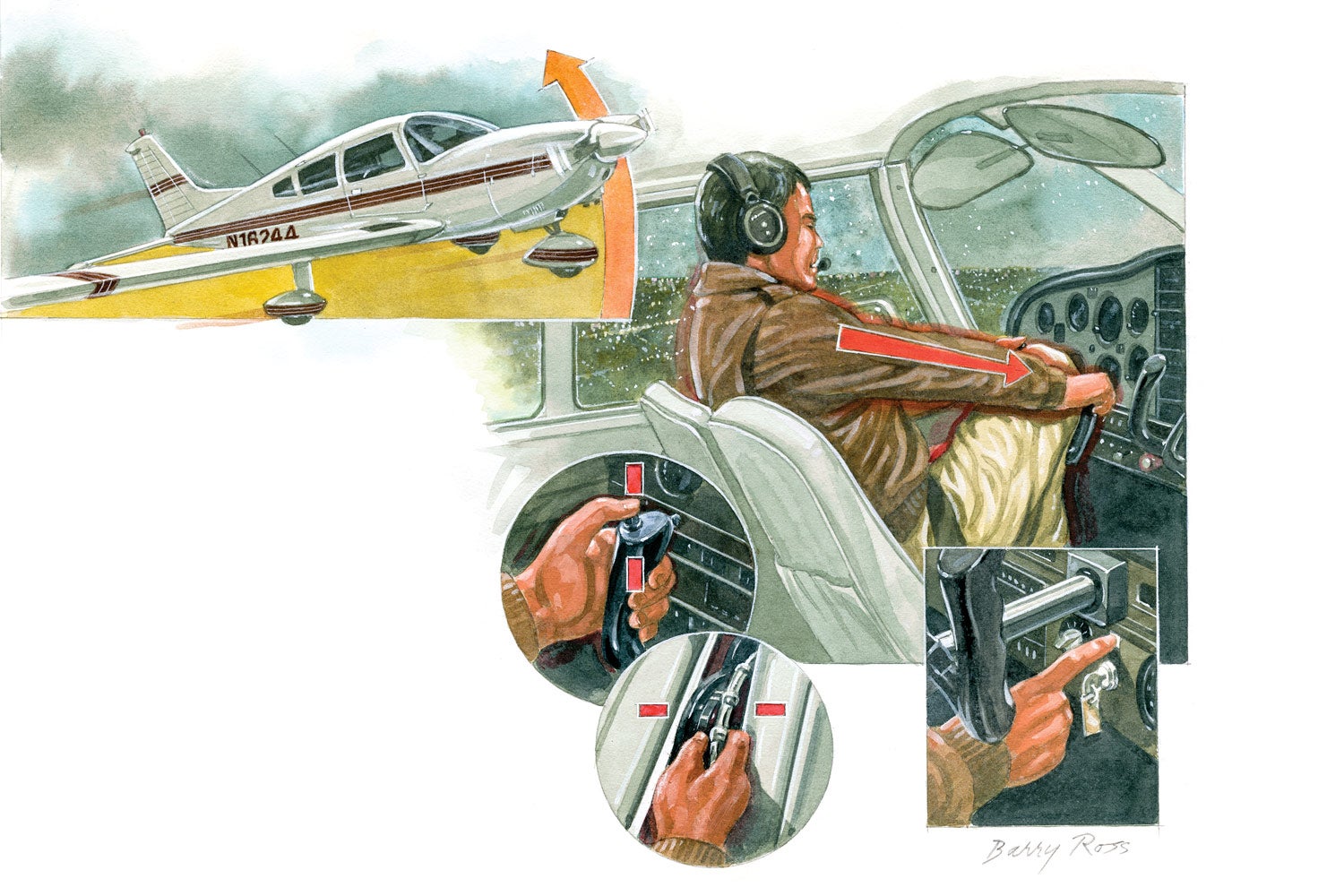

I arrived at the airport after dark and began my preflight. Of course, I was in a hurry, and upon entering the cockpit, I noticed that there were several differences compared to the Warriors I had learned to fly. While this gave me an uneasy feeling, the pressure of rescuing the abandoned student and CFI persuaded me to push on with the flight. Can anyone say, “Hazardous attitudes”? Specifically, I fell prey to two types of hazardous attitudes. The first was impulsivity. I noticed that the aircraft was trimmed somewhat nose high, but in my rush to leave, I reasoned that it would be OK. I also rushed through my preflight and checklists. Second, I displayed a macho attitude by agreeing with the flight school owner that I did not need to get a checkout in the aircraft.

Looking back, there were several differences compared to the other aircraft I had been flying—not the least of which was the Warrior’s tapered wing, while the older Cherokee bore a constant-chord, Hershey-bar wing. I finally made my way toward the active runway about 10 minutes before the tower closed. Once again—and you’ll note a theme here—I rushed the run-up and soon found myself taxiing onto the active runway. During the run-up, I noticed that the aircraft trim was set just on the nose-high side of neutral, but I surmised that I liked it trimmed slightly nose high for takeoff and climb, so I left it there. After receiving my takeoff clearance, I had a normal climb-out and was excited to be able to feel those extra 20 horses that the Warrior lacked.

Reaching 2,500 feet msl, I pushed the nose over to level the aircraft. Sensing the nose-high trim, I tried to use the electric trim to adjust the nose down—but nothing happened. Realizing that the electric trim was not functioning, I reached down and tried to turn the trim wheel manually to no avail. At this point, I was starting to have some trouble keeping the aircraft level, and my arms were starting to fill with lactic acid from fighting the airplane. My arms became so exhausted that I had to brace my knee against the yoke to keep the airplane somewhat level, while giving my arms a much-needed reprieve. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, I immediately called Columbus Tower before they closed and advised them that I had an issue and was returning to the airport.

Reality began to set in, along with panic, as I wondered how in the world I was going to get this airplane back on the ground in one piece. Reflecting on this incident with several hundred hours of experience, it doesn’t seem as intimidating; to the young, inexperienced pup behind the yoke back then, it was borderline terrifying. Flashbacks of rushing through the phone call with the flight school owner and the hurried preflight came crashing down in my head. For the first time in my life, I wished that I was on the ground instead of in the air.

As I turned the airplane back toward the airport, a miracle occurred. The tower controller asked about the nature of my problem, and after telling him of my quandary, he simply said, “Press the trim enable switch under the yoke.” I looked, and sure enough, there was a white switch under the yoke with no placard or any marking. I thought that must be it—and I had, in fact, wondered what that switch was during my preflight. After I pushed the button, the electric trim came to life, and I was able to relax and trim the aircraft for straight-and-level flight.

Read More: I Learned About Flying From That

In all of my arrogance of the day, I neglected the fact that, although similar to the aircraft I had been flying, there were definite differences in the Cherokee 180 that warranted getting a checkout. Luckily for me, I get to chalk it up to experience. Being a CFI, now I am able to draw upon that situation when talking to our local flying population about the importance of checkouts and flight reviews. The possible accident chain here was long, but interestingly enough the break came from none other than the Columbus Tower controller. Fortunately for me, the controller was the owner of the airplane and leased it back to our club for rental. What are the odds?

After gaining control of the trim wheel, I thanked the controller and turned around, heading to Lagrange to pick up the stranded pair. The rest of the flight was uneventful, and I would come to make many great memories in that old Cherokee. Looking back on this event, an unfortunately all-too-common situation occurred. I forwent calling the FAA to tell them what a wonderful a job the controller did because I was scared of getting in trouble. I’m sure he probably doesn’t realize the effect he had on my life—and for that, Mr. Harold Baker, I will be forever grateful.

You see, it’s this event that led me to apply to be and later become a certified professional controller myself. Day in and day out, I see these events and the quiet professionalism that these controllers exert, and I feel truly proud to be a part of their team. I encourage all pilots to use flight following and other services because we strive to provide a great product, and we go the extra mile to make sure that you make it to your destination safely.

My experience also makes for an interesting study of the FAA’s hazardous attitudes. Blinded by the thought of “free” flying time, I never stopped and considered the fact that not having a checkout, I could have driven to the airport in Lagrange and picked up the CFI and student. The time savings of flying versus driving would have been negligible.

Another note of wisdom I’ll leave with the general aviation community from the perspective of being an active CFI and air traffic controller: Never be afraid to ask ATC for help or declare an emergency. Many times, I hear pilots stress that they didn’t want to cause a lot of paperwork or get in trouble for declaring an emergency. Well I just want to say that the paperwork created is on our end, and it is our job to do it. Don’t worry about causing someone extra work or getting in trouble. Our job is to provide the best service possible and get you to your destination as safely as possible.

Finally, if you do have an experience like mine, call up your local ATC facility and let management know about it. We love to reward our controllers, especially because it seems that they go through most of their days anonymously. Be safe out there, and remember to never be afraid to ask for help and never gloss over the hazardous attitudes that make us susceptible to introducing unnecessary risk into our flying.