Mention the term “X-plane,” and most envision shadowy experimental military aircraft with mind-numbing performance. From the X-1, which was the first to break the sound barrier, to the X-15, which could cross the Karman line and enter space, X-planes have historically been defined by immense power, blinding speed, and sleek lines reminiscent of fictional spaceships.

Conversely, when discussing X-planes, most tend not to envision design features like an open cockpit, fixed landing gear, and a maximum speed only four knots faster than the cruise speed of a Cessna 182. Most also would not expect this category of aircraft to utilize second-hand Beechcraft parts. But these characteristics define the bizarre Bell X-14, an experimental vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) jet with a somewhat agricultural aesthetic. Further differentiating it from other X-planes was a second life as a trainer for NASA astronauts to refine their moon-landing skills and a dramatic last-minute rescue from a scrapyard.

Conceived by Bell Aircraft as part of a U.S. Air Force order to explore and develop VTOL technologies, the X-14 first achieved vertical flight in February 1957. It was among several of the first jet VTOL aircraft to take flight in the mid to late 1950s, a small group that included the Ryan X-13 and the British Short SC.1. The following year, the X-14 successfully transitioned from vertical to forward flight and began comprehensive flight testing at Bell’s facility in upstate New York.

Originally utilizing two nose-mounted Armstrong Siddeley Viper turbojet engines, the X-14 was later upgraded to General Electric J85 turbojet engines—as used in the Cessna A-37 Dragonfly—that produced a total of 6,000 pounds of thrust. This thrust was controlled by a series of vanes within the belly to maneuver the 4,269-pound aircraft. Rather than employ separate engines for forward thrust, the system could direct the thrust downward for takeoff and landing or rearward for conventional flight.

Accurate pitch, yaw, and roll control has historically been a challenge for jet-powered VTOL aircraft. To achieve this, the X-14 utilized a system of bleed air and mechanical spool valves at the tail and at each wingtip. With careful application of the stick and rudder pedals, the pilot could command short blasts of bleed air to nudge the aircraft into the desired attitude during flight.

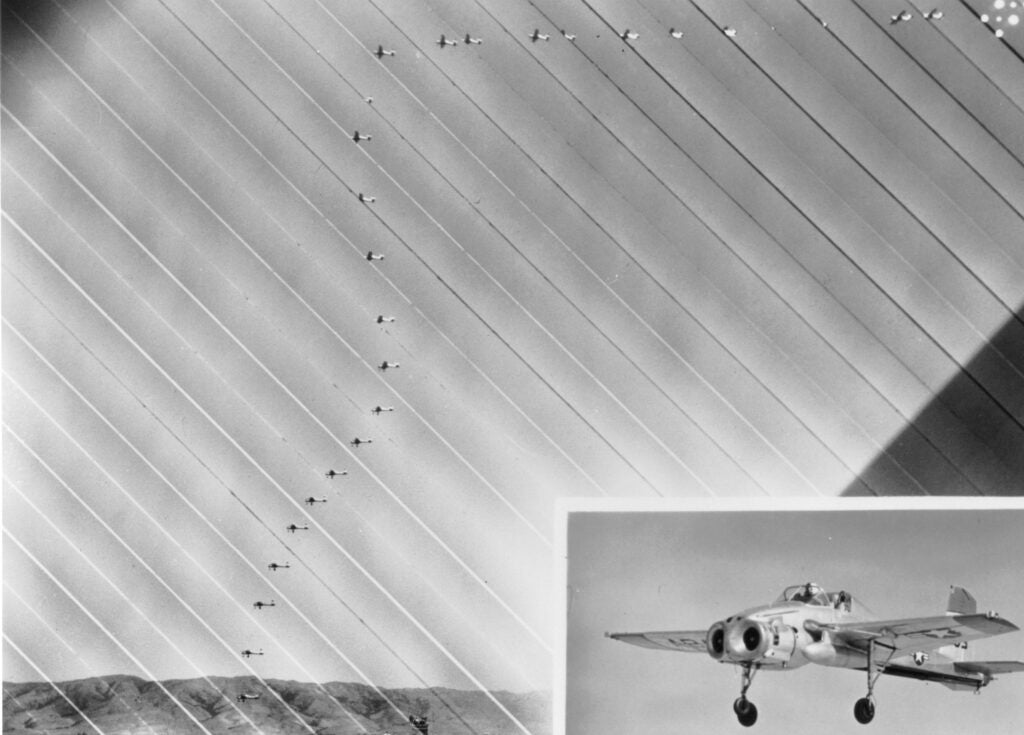

Bell and the U.S. Air Force tested and evaluated the X-14 and invited pilots and engineers from abroad to participate, thus supporting the development of what ultimately became the VTOL Harrier attack jet. As the X-14’s first chapters of testing drew to a close, NASA took interest. The Apollo program was about to begin, and officials recognized the need for specialized astronaut training. While Gemini had proven astronauts could get to and from space, NASA now needed to train astronauts to precisely maneuver the lunar lander to a predetermined point on the moon’s surface.

Lacking easy access to a training environment with limited gravity, they employed the X-14, reasoning that the bleed air maneuvering system bore a reasonably close resemblance in practice to the thrusters used to maneuver the Lunar Module. After shipping the X-14 to the Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California, astronaut flight training commenced. NASA also utilized the X-14 to help develop a more comprehensive training platform, the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV).

Among the numerous pilots to fly the X-14 was Neil Armstrong. He put the aircraft through its paces, learning to “perch on a bubble of hot air,” as he reportedly described the hover. Armstrong also reportedly claimed the X-14 was the only aircraft in which he could execute a zero-radius loop, flopping around its center of mass “by deft manipulation of the throttle, nozzle control, and stick.”

All such maneuvers were conducted directly above the airfield of origin, as the total fuel capacity of 110 gallons resulted in as little as 20 to 30 minutes of endurance. Armstrong reportedly ran the tanks dry on more than one occasion, and he compared its glide characteristics to that of a Cessna 206. With Beechcraft wings, the handling would have indeed seemed docile, particularly compared to the F-104 and the hypersonic X-15 he had been flying.

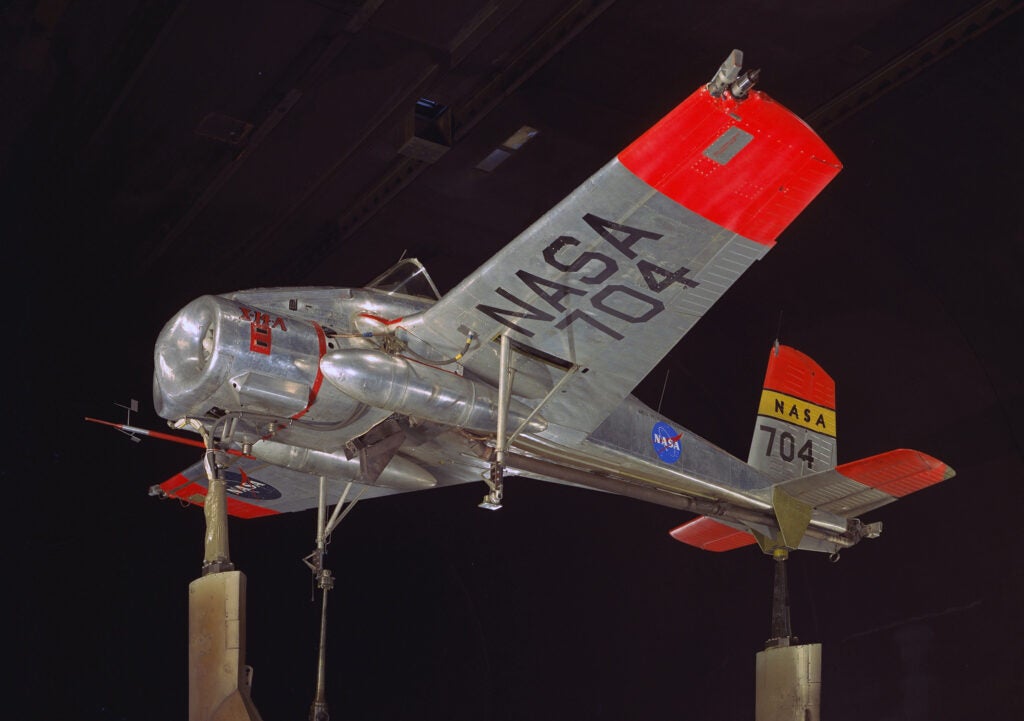

After the X-14 had served its purpose with NASA, it was entrusted to a government entity that initially had plans for restoration but ultimately placed it into long-term storage. Decades of being disassembled to various degrees and moving from place to place took a toll. Sections of the airframe were damaged, the brightly-polished aluminum skin became weathered and dull, and when it ultimately began to resemble a pile of discarded scrap, the entire thing was eventually sent to a scrapyard.

When an aircraft arrives at a civilian scrapyard, it typically doesn’t take long for it to be erased from existence completely. Fortunately for aviation enthusiasts and historians, however, a man named Rick Ropkey learned about the X-14 before it succumbed to that fate. In the late 1990s, upon learning of its condition and of the plan for it to be scrapped, he purchased it and arranged for it to be trucked to his family’s military history museum in Indiana, the Ropkey Armor and Aviation Museum.

Ropkey was not satisfied with rescuing only the aircraft itself. He also managed to locate and salvage a massive amount of materials related to the X-14, including large-scale blueprints, various forms of test data, and boxes of manuals, some of which had been initialed “N.A.” Familiar with the aircraft’s history, Ropkey reached out to an old fraternity brother who knew Neil Armstrong personally and eventually got in contact with the legendary astronaut. Before long, Ropkey and Armstrong were on a first-name basis, and Ropkey was able to gather unique, first-hand accounts of the X-14’s history.

Over the years, Ropkey and his son Noble gradually worked through the restoration process, restoring one part at a time while keeping the X-14 on display in their museum. When Ropkey’s father died in 2017, the museum was forced to relocate. Presently, plans are afoot to display the X-14 again, and the restoration is nearly complete.

While the family has no intention of ever flying the X-14, they are striving to complete a full restoration and share it with the public. Presently, the most significant challenge is sourcing parts for the GE J85 engines, and Ropkey hopes to find a source willing to donate surplus engine parts. “It’s been a labor of love for the last three decades,” Ropkey said, and added, “It’s going to be in the Ropkey hands for a long time.”

After surviving 24 years of operation with no major accidents or serious injuries, and after countless landings by astronauts-in-training, aviation and history enthusiasts alike are fortunate that the unique X-14 has landed in the hands of a family with a strong appreciation for it and its legendary history.