Constructed in 1942, Freeman Army Airfield in Southeastern Indiana was a training base for U.S. Army Air Corps bomber pilots through 1944. It became the Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center after World War II ended.

Near the war’s end, it was also the site of a pivotal civil rights battle that helped desegregate the armed forces.

In 1945, dozens of Black officers who were part of the 477th Bombardment Group and Tuskegee Airmen members attempted to enter the white officers’ club at Freeman. More than 100 were arrested and charged with violating base regulations. The incident became known as the Freeman Mutiny and helped catalyze President Truman’s efforts to ensure equality of treatment and opportunity in the U.S. military.

From Farms to an Airbase

The Army built Freeman to train pilots on multiengine aircraft and instrument-only flying. They named the base in honor of Captain Richard Freeman, a Distinguished Flying Cross recipient, who died in a B-17 accident in 1941. Nearly 2,600 acres of local farms were turned into an airbase with 413 buildings and four 5,500-foot runways.

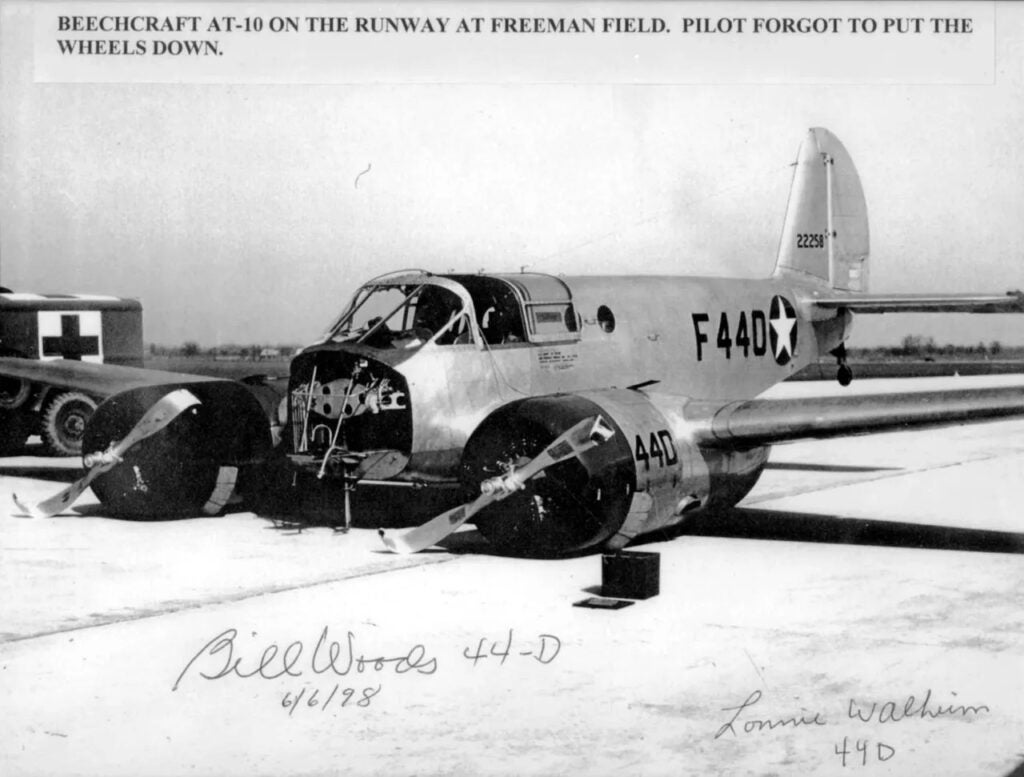

From 1943 to 1945, more than 4,000 pilots trained on Beechcraft AT-10s. Nineteen classes graduated, with many pilots headed to other bases for a third stage of training on bombers and transports. In 1944, Freeman also became the first U.S. helicopter training base.

In March 1945, two squadrons of the Tuskegee Airmen were transferred to Freeman Field from Godman Field in Kentucky. These were not the famed 332nd Fighter Group Red Tails. They were part of the 477th Bomb Group, the first Black bombardier group in Air Corps history, headed to Freeman to continue their training on B-25 Mitchell bombers.

The 477th was established in 1943 and activated a year later under a white commander, Colonel Robert Selway. This was the era when segregation was still practiced in the military. Despite regulations entitling any officer entrance to base officers’ clubs, Selway effectively established segregated facilities by designating one club for supervisory personnel, all of whom were white, and another for trainees, all of whom were Black. The trainees’ club, sometimes dubbed “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” was conspicuously inferior to the one for white officers.

Over successive days in early April of 1945, groups of Black officers attempted to enter the de facto white club, claiming their rank entitled them entrance. One handful purportedly pushed their way past the Provost Marshall. Ultimately, 61 who attempted to enter were placed under arrest. Charges were subsequently dropped for all but three who allegedly shoved their way into the club. Two were exonerated and released. Second Lieutenant Roger Terry was found guilty of assaulting a superior officer. He was stripped of his rank and dishonorably discharged.

In reaction to the incident, Selway redrafted regulations (known as Base Regulation 85-2) detailing who could use which base facilities. Violating 85-2 was a chargeable offense, and all base personnel were expected to sign to acknowledge their understanding. However, 101 members of the 477th refused to sign the document and were subsequently charged with insubordination. The men were placed under house arrest and eventually returned to Godman Field to await trial.

While the army tried to keep the affair under wraps, word spread to the Black press. Journalists who showed up the day the arrestees were being transported back to Godman Field had their cameras confiscated or destroyed. However, Sergeant Harold Beaulieu, who ran Freeman’s photo lab, hid a camera in a shoebox and managed to snap a photo which he forwarded to the Black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier.

The picture spurred a flood of protests to the War Department from Black groups and individuals. Thurgood Marshall even became involved. Congress intervened and applied pressure on the Army to drop the charges against the men. Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall released all the pilots in late April, but not before letters of reprimand had been placed in their administrative files.

That May, the War Department determined that Selway’s Base Regulation 85-2 violated the Army’s Regulation 210-10 and relieved him of command. Four decades later, at the request of surviving veterans of the 477th, the Air Force removed the letters of reprimand from the files of the airmen involved and issued a full pardon and restoration of rank to Roger Terry.

The Freeman Mutiny was not a proud chapter in Freeman Field’s story, but it helped usher in President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981 in 1948, establishing equality of treatment and opportunity in the U.S. armed forces regardless of race, color, religion, or national origin.

Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center

After WWII ended, Freeman became home to the Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center. Some 160 German, Italian, and Japanese aircraft and German rockets were relocated there for reverse engineering and study. Most arrived partially disassembled, although some larger bombers were flown intact.

Some of the airplanes were reassembled and flight tested, while others were simply dissected for analysis. Because there were so many aircraft at Freeman, there was discussion of making it the home of a national Air Force museum. That honor eventually went to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

After the Evaluation Center was decommissioned in 1946, most flyable or intact aircraft remaining at Freeman were transferred to other locations, including Wright-Patterson and the Smithsonian. Those remaining were scrapped and often buried around the grounds. In the 1990s, several salvage companies expressed interest in digging for aviation artifacts at Freeman. Rumor had it that as many as 14 intact planes were buried there. The efforts were chronicled on National Geographic’s TV series “Diggers.” While artifacts were found, no complete airplanes or intact engines were discovered.

Freeman Army Airfield Museum

The base was eventually sold to the city of Seymour for $1 with the understanding that it would continue as an airport. In 1996, the airport authority authorized using a remaining Link Trainer building as a museum. The museum opened in 1997, filled with artifacts, many donated by local residents. A group of Tuskegee Airmen were its first visitors.

Cadet reunions held for pilots, staff, and their families stationed at Freeman during WWII yielded additional donations, filling the original building to capacity. In 2002, a second building was added. Today, visitors can tour both buildings, filled with WWII-era artifacts like a Link Trainer, engines, propellers, and other aircraft artifacts from both theaters of WWII (many of which were excavated from the grounds). One of two original base firetrucks is on display. The fully roadworthy vehicle often makes local appearances.

The story of the Tuskegee Airmen was brought back to national attention when local Boy Scout Tim Molinari came up with the idea for a permanent dedication. Molinari spearheaded efforts that raised $70,000 for a historical marker, two lifesize Tuskegee Airmen sculptures, and bringing the Rise Above traveling exhibit about the Tuskegee Airmen to Seymour.

In an interview with the IndyStar newspaper, Molanari said, “Despite the monumental events that took place out there at Freeman Field, there really wasn’t anything that marked the historical events that took place.”

Attending the 2015 dedication was Brian Patrick Avery, the grandson of photographer Sergeant Harold Beaulieu and author of the children’s book, “The Freeman Field Photograph.” In an interview for Indiana Public Media covering the dedication, Avery commented, “These statues and the men who stood out on the flight line and my grandfather represent the greatest of patriotism in our country,” adding, “It’s important that we remember, these men were patriots…You can love your country and work for it to be better, and you can still be a patriot.”