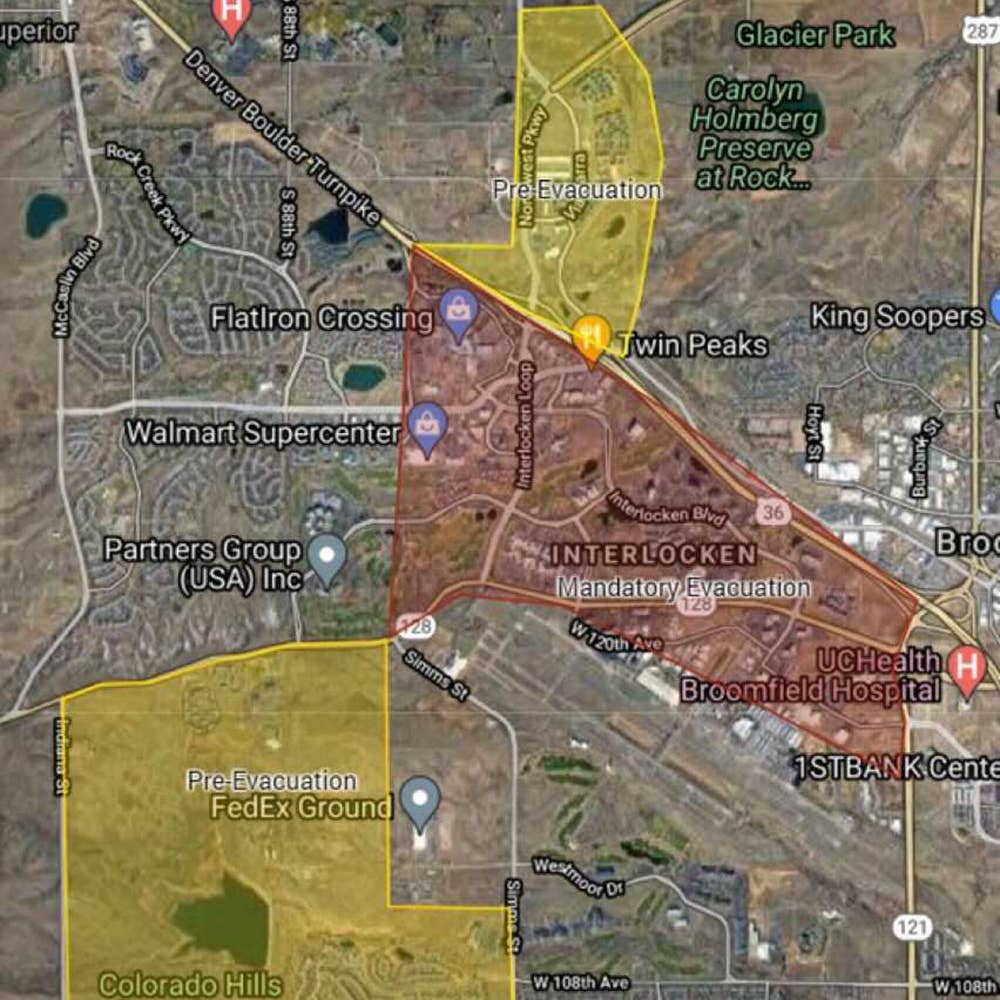

The evacuation map for parts of Boulder County, Colorado, illustrates how serious the situation was. [Courtesy: Broomfield City and County Government]

Pilots based on the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado know that the winter brings on the mountain wave.

What they don’t expect in winter? For that wave to feed a storm of flames on the ground.

On Thursday afternoon, a grass fire likely sparked by downed power lines around Marshall was stoked into a massive conflagration by those winds. The fuel from a wet spring and subsequent extreme drought lasting through the fall—and the fact there’s no snow cover around the Denver metro area in late December—made for what felt like a freak event.

Unfortunately, adjacent suburban communities lit up quickly in the rapidly advancing firelines. In the nearby towns of Superior and Louisville, more than 570 homes had been reported destroyed as of Friday afternoon.

Rocky Mountain Metro Evacuates

The general aviation reliever airport for the north side of Denver, Rocky Mountain Metro Airport (KBJC) sits just to the south of the fire’s initiation point, on a broad mesa.

Metro is home to several flight schools, Signature and Sheltair FBOs, Spartan College of Aeronautics’ Broomfield Campus, and a multitude of other GA businesses.

It’s also the site of Pilatus Business Aircraft, the U.S. headquarters and completion center for the Swiss manufacturer of the PC-12 NGX turboprop and PC-24 light jet. The OEM’s new 188,000 square ft facility opened in 2018.

By Thursday afternoon, much of the airport lay inside the mandatory evacuation zone—and was besieged by the plume of smoke—prompting its closure by late afternoon. The last METAR posted around 3 p.m. local time, and regular reporting resumed Friday morning.

Early reports from the area indicate that the airport was largely spared—including Pilatus—as it sits about 2 miles from the southern edge of the known fireline.

How a Mountain Wave Works

The furious stream of air that funnels over the Continental Divide and races down through the foothills below is generated when the air is cold and stable, forming layers between which the prevailing winds at mid-level attitudes (normally between 12,000 ft and 24,000 ft msl) can accelerate and cascade in what appears to be a sine wave, high over the rocks below.

In the lee of the mountain range, that wind drops down and creates the mighty gusts that periodically plague the Colorado plains from Pueblo to Fort Collins.

While the mountain wave will often generate telltale cloud formations both at altitude (altocumulus standing lenticulars or ACSLs) and at pattern height (rotor clouds), it’s mostly an invisible phenomenon and hard to visualize.

Denver7 viewer Mario Gori shared this timelapse of the MOUNTAIN WAVE helping to fan the flames of the #MarshallFire. This phenomena is like waves crashing on a beach, feeding the fire like bellows! @denverchannel @NWSBoulder #cowx @ClimateCentral @WeatherGeeks pic.twitter.com/aMjVWQApat

— Mike Nelson (@MikeNelson247) December 31, 2021

With the introduction of massive amounts of smoke and particulate matter into the wave—or föhn—winds, however, the outlines of their power caused pilots, meteorologists, and weather spotters across the metro area to capture photos and video.

The pronounced lee wave—so called for its position in the lee of the mountain range—was called out by several weather observers, including remote ones such as professor of atmospheric science Neil Lareau.

Pronounced stationary lee-wave signature in the #MarshallFire plume. Likely all sorts of complex flows at the surface (flow separation and reversal) #cowx pic.twitter.com/rlgdOmPlRq

— Neil Lareau (@nplareau) December 30, 2021

The plume itself was visible for nearly 100 miles in the otherwise clear winter afternoon, bearing witness to the power of the downslope winds—and how they might affect aircraft in flight.

Scary video of Boulder windstorm and fire. Evidence of hydraulic jump and downstream rotor. https://t.co/9SIXnFWWlA

— Jim Steenburgh (@ProfessorPowder) December 30, 2021

Other associated phenomena were observed as well, including the Kelvin-Helmholtz breaking wave formation downwind of the fire.

Interesting Kelvin-Helmholtz breaking wave formation along the smoke plume of the #MarshallFire in Colorado, as seen in #GOES16/#GOESeast True Color RGB images (created using @UWSSEC #Geo2Grid): https://t.co/jNEFueooXR #COwx pic.twitter.com/9rEnxTNbzX

— Scott Bachmeier (@CIMSS_Satellite) December 31, 2021

The Recovery Begins

Aviation will play its part in the firefighting and recovery efforts where possible. From a base at Denver Centennial Airport (KAPA) last night, a multi-mission Pilatus PC-12 operated by the state of Colorado flew reconnaissance over the fire area, as local winds died down enough to allow for flight operations to begin again.

Colorado state multi-mission aircraft up doing reconnaissance right now. #Colorado#MarshallFire#Boulder #wildfire

— 🇵🇹Common Raven🇺🇸 (@Bewickwren) December 31, 2021

Flight from Denver to Denverhttps://t.co/ivmqRpokeM pic.twitter.com/Qg7EmJ2i7U

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox