The fast-moving cold front bristled against the western edges of Washington's Cascade Mountains. Rain showers and gusty winds swirled through the valleys as thick clouds enveloped the rising terrain. Darkness had long since fallen that February night as clock hands edged past 10 p.m.

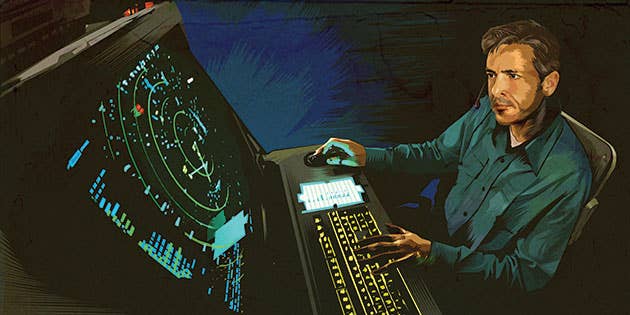

Air traffic controller Jared Mike plugged his headset into the workstation at Seattle Tracon (terminal radar approach control). Housed in a nondescript building just west of the Sea-Tac Airport, the facility handles arriving and departing aircraft transiting the southern and central Puget Sound area. Sea-Tac, Boeing Field and McChord Air Force Base are just a few of the busy airports within its airspace. Mike would be working through the night amid the control room's hushed dimness.

His flat-panel "scope" depicted aircraft as uniform blue blips moving in various directions. Each toted readouts of the airplane's flight number/callsign, speed and altitude. The display might have resembled a video game, but Mike never forgot that the dots embodied real aircraft and people. Most of the traffic was climbing eastbound — airliners destined to cities beyond the screen's range. Some precipitation painted along the Cascades with each sweep of the scope's radar, but the aircraft were flying safely above the cold front's perils.

Mike transmitted his instructions to the aircraft's pilots in the calm and measured cadence he had honed over a seven-year career. The 31-year-old keenly understood that his voice ultimately controlled the traffic. If his instructions were clear and concise, the pilots would follow them without hesitation; if he stammered or his voice cracked, his directives may not be trusted. If he was confident, then pilots would be confident in him.

While methodically issuing altitude and routing clearances to the airliners, Mike noted the lone westbound blip on his scope. Unlike its high-flying counterparts, the Piper Seneca II slowly edged across the blackness as it battled headwinds. Mike instantly recognized Flight 55. The small, twin-engine propeller airplane belonged to a Seattle-based freight company that flew the Seattle-Spokane round trip almost daily. Flight 55 was one of the operator's numerous cargo aircraft that frequently crossed the Tracon's scopes.

A Routine Flight

The routine helps controllers refine their highly specialized skills; it also provides familiarity to their demanding job. Mike watching Flight 55's usual trundle across the Cascades should have foreshadowed an uneventful midshift as his wife and children slept at home. The Seneca was flying its usual route at its normal time. There was no reason to think it would not pass through his airspace with its normal ease.

Mike shifted his attention back to other traffic within his airspace. The Seneca had not quite reached his sectors. He did not give the aircraft a second thought — he would be talking to its pilot soon enough when he routinely checked in on Seattle Approach's frequency. The early minutes of the overnight shift continued passing as expected.

While Jared Mike settled in at the Tracon, pilot Phillip Bush guided the Piper Seneca westward. Despite the strong headwinds, Flight 55 was slated to land at Boeing Field on schedule with its time-sensitive freight. The flight from Seattle to Spokane just hours earlier had been uneventful. Bush knew the weather over the Cascades could change quickly, but the turbulence now buffeting the Seneca was still unexpected. The aircraft jolted as the air roiled off the terrain below. The cargo, bungeed down directly behind Bush's worn seat, strained against its straps. Passing the town of Ellensburg, he coaxed the Seneca upward to 13,000 feet, where smoother air hopefully waited.

The small and slow aircraft starkly contrasted with the EA-6B Prowlers that Bush had aviated in the Navy. The Seneca was built in the late 1970s, and with the exception of the GPS retrofitted into its cramped cockpit, the avionics belonged to yesteryear. Bush continuously scanned the clocklike instruments to cross-check his altitude, airspeed and course. Vacuum and static pressure powered the dated indications while a 14-volt electrical system energized the radios and lights. This charge could not have made the Prowler's signal-jamming technology even flicker.

As the Seneca's piston engines wheezed through the Cascades' thin air, it was difficult for the 36-year-old to forget the power of the Prowler's turbojets. Over two tours in Afghanistan, he had throttled the aircraft through 240 combat missions and earned 12 air combat medals in the process. Climbing above turbulence had been fast and easy; the Seneca, however, struggled to ascend as the invisible mountain waves gripped its stubby wings.

Bush gazed into the bumpy darkness and glimpsed the outlines of the land where his dreams originally took flight. Washington's beauty was always home. Skirting Afghanistan's scarred terrain allowed him to serve his country, but his native state always beckoned. After separating from the Navy in 2010, flying single-pilot night freight over the Cascades posed a new challenge — one that he always wanted to accomplish.

Piloting the Seneca had its quirks, but the venerable bird returned home every night. Flying alone also had its advantages. The empty co-pilot's seat relinquished Bush to his own thoughts and memories as Washington slid beneath.

When he was 40 miles from the airport, he started his descent into the Emerald City. Gently pulling back the throttles eased the Seneca's pitch downward toward the waiting clouds. The turbulence remained but Bush believed that it would not worsen. The forecast called for a fast-moving cold front to affect the area, but it was not supposed to arrive until after he parked at Boeing Field. He would be talking to Seattle Approach in a few minutes. The controller would guide him to within a few miles of the airport.

The Seneca continued descending as its navigation lights began reflecting off the cloud tops. Bush knew the clouds' moisture would likely result in ice adhering to the aircraft.

He turned on the pitot heat, which protected his airspeed indicator; his right index finger shadowed the rocker switch that activated the deicing boots. The rubber devices lined the leading edges of the wings and tail. They inflated to dislodge accreted ice to ensure airflow was not disrupted over the Seneca's aero-dynamic surfaces.

Bush focused on his instruments as the clouds began engulfing the airplane. He noted the outside temperature as minus 15 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) and remembered that it was at least above freezing on the ground. The Seneca, meanwhile, lurched as it fully entered the clouds and became cocooned in the wet blackness.

Mike suddenly realized something was terribly wrong as he watched Flight 55's blip on his scope. The Seneca pilot's voice sounded strained when he curtly requested lower altitudes and reported light to moderate icing in his descent through periodic rain. It was clear the pilot could not comply with the assigned altitude of 8,000 feet as the scope's readout flashed 7,600. Mike quickly issued a revised clearance to maintain 7,000 feet while referencing the area's minimum safe altitudes. The fellow Washington native knew that rocky terrain lurked below.

"[Flight] 55," he calmly transmitted, "are you having a hard time holding altitude?"

"Yes, sir."

" … 55, roger. My safest altitude I'm showing is 5,400. That's my safest altitude. … If you can hold 7,000, maintain 7,000."

"I'll do what I can … 55."

"Yeah, no problem. Are you out of the precip yet?"

"Nope."

"Roger. In a few more miles I can get you down to six [thousand], sir."

"I'm going to be down to six no matter what."

" … 55, roger that. … Five thousand four hundred is a safe altitude if you have to keep [descending]."

Mike had developed an innate ability to discern a pilot's tone. His ears had heard thousands of radio calls throughout the years. He recognized that Flight 55's pilot was stressed, but unsettling inflections accompanied his transmissions — the man flying the Seneca was scared.

Mike watched the blip as he changed his scope to the emergency vector map. A rudimentary pictorial of the surrounding terrain appeared with corresponding safe altitudes defined within the peaks. He watched Flight 55 continue its descent. If its pilot was not able to arrest the altitude loss, the blip would vanish from the scope as the Seneca barreled into the Cascades.

Bush's left hand, meanwhile, wrestled the Seneca's paint-chipped control yoke. The aircraft thrashed and bucked in the darkness as severe turbulence pummeled its control surfaces. Boxes smashed against the cabin as Bush's shoulder harness snapped taut. The instruments became hard to decipher as he fought to keep the wings level. Invisible wind currents tossed the Seneca about like a toy. The airspeed indicator's needle jumped between 90 and 160 knots. It was eerily quiet as the gusts abated and the speed decreased; it became deafening when the slipstream howled. Bush's right hand worked the Seneca's throttles to correct for the sudden fluctuations. Rain continuously pelted the fuselage as if hurled by a sandblaster.

Collecting Ice

The first signs of icing had appeared while descending through 10,000 feet. A thick coating had built along the leading edges of the Seneca's wings. Bush had pressed the rocker switch to cycle the deicing boots as the aircraft careened through the bumps. He had encountered severe turbulence and icing during past Cascade flying; however, he'd never imagined he would contend with both simultaneously.

Passing 9,000 feet, the Seneca's airspeed indicator had plummeted to zero. The electric pitot heat had not been able to shed the severe ice. Bush could only estimate his speed from the sounds of the wind. When every cockpit window had iced over, he'd slammed the throttles forward. The Seneca's engines had surged as they strained to deliver full power. The aircraft had become a flying ice cube. Bush knew speed equaled life — even if the foreboding wind noise of the ferocious turbulence was his only means to guess his velocity.

The only escape was a lower altitude. Warmer temperatures would help shed the ice from the airframe. Leveling off was impossible. When Bush had tried maintaining 8,000 feet he sensed the decaying airspeed. The weight of the ice combined with the reduced airflow over the Seneca's critical surfaces had increased the airplane's stall speed — the point when it could no longer generate lift. Bush knew a stall would be unrecoverable. He'd hoped he would find warmer air before the Cascades' terrain found him.

Fortunately the Seattle Approach controller had realized the severity of his predicament. The calm and collected voice that filtered through the rain and wind had cleared him to lower altitudes without hesitation. Keeping the Seneca from stalling in the ice and turbulence was all-consuming; maintaining course was another matter. Bush tried holding a westerly heading as the turbulence continued.

Mike watched Flight 55's blip intently. It unabatedly slid toward the terrain displayed on his emergency map. The descending Seneca already did not have the altitude to clear the hills ahead; turning was the only means to prevent disaster. Mike's thumb shadowed his transmit switch. Before depressing the button, he silently repeated to himself a coveted mantra from his initial training: Stay clear and calm; make them trust you. He breathed and squeezed the push-to-talk key.

"[Flight] 55, if you turn … a slight five degrees left … safe altitude is 3,700."

"I'm turning left and I'm continuing my descent, 55."

" … 55, I'm just going to let you know that I'm declaring an emergency for you for icing."

"Affirmative."

"[Flight] 55, I just need to get some info from you. … How many souls on board and fuel?

"One on board and I've got 2½ hours of gas."

Mike sighed as Flight 55's blip was coaxed by the terrain. The emergency map depicted an unnamed and narrow valley unrolling to the Seneca's right. The aircraft was still descending. The previous vector had avoided one hill; now Mike had to truly thread the proverbial needle.

"[Flight] 55, turn 20 degrees right, then … you can get down lower for safe altitude."

"And what altitude do you have for me, for 55?"

" … 55, 3,700 is safe right there."

"Great, going down."

Mike noted the Seneca wedge into the valley. Its blip was tightly nestled between two peaks outlined in the emergency map's greenish lines. The Seneca was flying below the walled sides that were only 1½ miles apart. Privately, Mike hoped the pilot was not flying through the valley of death. The Seneca was momentarily safe but its troubles were not over. He shifted his scan to the other traffic on his scope and started transmitting instructions in his customary tenor. Flight 55 was not the only aircraft on frequency. Mike would not be doing his job if he neglected them.

Bush did not need to see through his iced windscreen to know that he was in danger of crashing. The flashing red GPS terrain warnings were abundantly clear. Rocks cloaked in the wet clouds were perilously close. He wondered what hill awaited him as the Seneca's pistons continued firing at full power. The lower altitudes did not offer the much needed reprieve of warmer temperatures. The ice was unrelenting, as was the turbulence.

Bush noted his shaking right hand as he periodically released his grip on the throttles and cycled the deicing boots. It was another disconcerting sight amid the GPS's warnings and unwinding altimeter. His hands never shook during his Afghanistan missions, nor did they tremble when making night landings on aircraft carriers. The Cascade Mountains in his beloved home state ironically generated the true fear. Bush felt helpless as the Seneca continued its descent and he struggled to keep the airplane airborne. The cockpit was becoming his iced-over coffin.

The controller's calm and confident voice filling his headsets was the only semblance of order amid the chaos. Bush understood the vectors were the controller's attempt to steer him through the terrain. His voice had become eyes that saw through the clouds and ice. Mike knew death could be imminent but his voice remained clear and crisp. His tone and cadence did not waiver.

Bush sensed the controller's presence as he fought to turn the Seneca 20 degrees right. The confidence in Mike's voice generated a glimmer of hope that he could possibly skirt the Cascades as he continued his descent to warmer air. The copilot seat was empty, but Bush felt as if the controller were sharing the cockpit with him. He took comfort that he would not die alone — the controller would be with him until the end.

Hearing his voice was a lifeline. It guided Bush through the terrain and kept him connected to the world beyond the Cascades' deathly grip. Life still existed outside his frozen tomb. The controller was the key to survival as his voice unlocked the turbulent and iced-over doors.

"How am I looking for 55?" Bush transmitted.

" … 55, you're good on altitude right now. That's good. You can [go] straight ahead, hold your current heading. That's good altitude right there. Continue your descent, that's good."

"55."

" … 55, right now I can get you down, almost down to about 2,000 feet if you go slow. … Hopefully you'll break out [of the clouds] soon."

Mike again reminded himself to stay calm as he transmitted his instructions to the Seneca's pilot. The aircraft's blip continued edging through the valley's walled sides. If the pilot was able to maintain his course, he would exit into the flatter terrain of Seattle's eastern suburbs. The lower altitude would hopefully be warm enough to finally shed the ice. The Seneca was now passing through the needle's eye. Mike could only wait and hope the airplane did not get pricked by the valley's sides.

Phillip Bush began glimpsing a most welcome sight. The GPS's red warnings had ceased and the thick clouds started becoming ragged. Sporadic lights from the ground began glimmering through the small window spots that had not accrued ice. He was finally close to breaking free of his gray prison.

" … 55, how're you holding up?" came the controller's voice.

"Eh, pretty well. These clouds are starting to break up a little bit."

" … 55, good. Let me know when you're in the clear."

A few minutes later the Seneca broke through the cloud bases and into the Seattle night.

"And, uh, [Flight] 55, it looks like I'm just below the clouds. I'm so iced up that my, I can't even see off my right."

" … 55, roger that. … Let me know how you're doing on icing, if you're starting to melt away there."

The timeliness of the transmission did not surprise Bush. The controller was there every time he needed him. He watched the ice start to disperse from his beleaguered aircraft. The lights of the town of Renton were glorious in the distance. Boeing Field was just beyond the welcoming glow.

"Yeah, just as you said that, it's starting to peel off my windscreen," he transmitted. "I'm starting to be able to have some forward visibility."

" … 55, great, sounds good."

Bush steered the Seneca toward the airport. His left hand began to relax on the yoke as the aircraft's normal handling characteristics returned. The highways, lights and buildings of Seattle's downtown combined to form a picture of euphoric certainty. Bush knew his exact position; the nightmare was over.

"I think I'm able to cancel [my flight plan]," he said to the controller. " … I'll head on in to Boeing Field."

" … 55, roger. Cancellation [received], just remain on my frequency a little bit longer."

"55."

Mike watched the Seneca's blip on his scope. Its altitude was finally controllable. The pilot had managed to survive the hellish ordeal.

" … 55," he transmitted. "Great job."

"Thank you, sir. You too."

Making the Difference

Mike continued watching Flight 55 after he handed the pilot off to Boeing Field's tower controller. He was relieved when the Seneca touched down, but the moment was fleeting. Other aircraft that required instruction were transiting his sectors. Mike pushed his push-to-talk button and let his composed voice fly across the airwaves. It was just after 10:30 p.m. local time; his midnight shift was just beginning.

Jared Mike was honored for his exemplary conduct in helping save Phillip Bush's life that February night in 2013. He was awarded the Archie League Medal of Safety (named for the first air traffic controller) by the National Air Traffic Controllers Association. This distinction is bestowed upon members who demonstrate paramount skill and judgment — qualities that save lives. Mike was among 20 controllers from across the country to receive this annual accolade last year.

Phillip Bush appeared at the awards banquet in Las Vegas. He emotionally conveyed to the audience how Jared Mike had saved his life. "I am here for Jared Mike," he explained to the hushed crowd. "I am here because of Jared Mike."

A controller's voice is a powerful entity. Cadence and tone are essential to performing a demanding job within a challenging environment. The sounds of voices emanating from air traffic control facilities issuing clearances and instructions are a cornerstone of the national airspace system.

Yet the sound of a voice can also elicit emotion steeped in memory. Phillip Bush often hears Jared Mike's radio calls over Seattle Approach's frequencies. The men always exchange pleasantries as Mike watches over Bush's aircraft. The controller issues routine instructions in his honed parlance; Bush acknowledges as his native state passes beneath the Seneca's wings. He knows he will never forget the sounds of Mike's words. The controller's voice is what truly brought him home.

Get online content like this delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for our free enewsletter.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox