Remembering Lt. Col. Alexander Jefferson’s Lofty Dream

A Tuskegee Airman flies west after more than a century of mentorship and leadership.

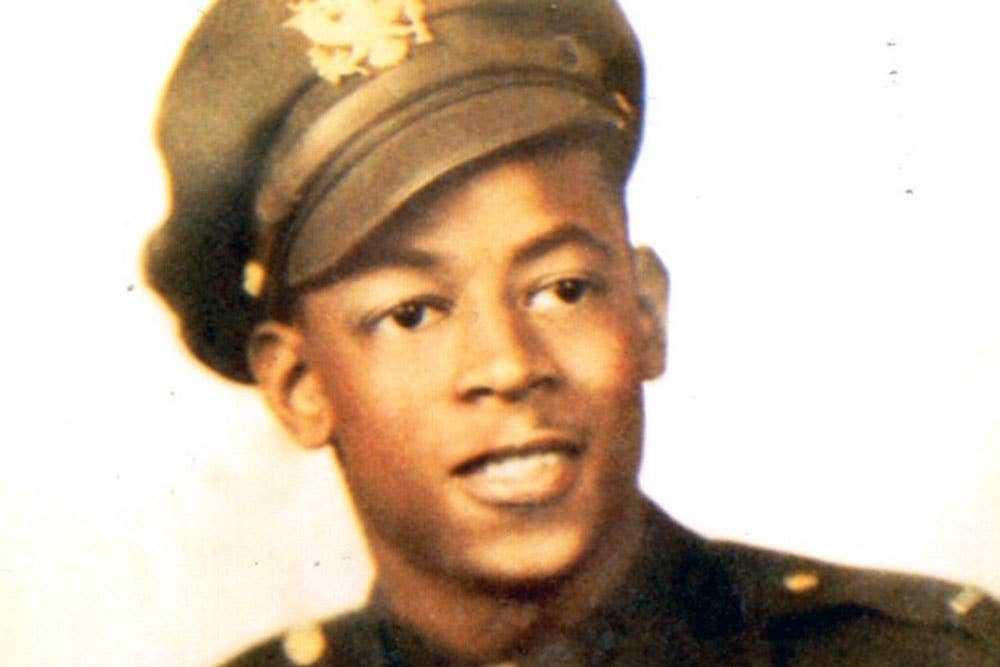

Alexander Jefferson earned the coveted silver wings of an Army aviator at the historic air base in Tuskegee, Alabama. [Courtesy: City of Detroit]

On June 22, the country lost a patriot, southeast Michigan lost one of its most distinguished citizens, the Air Force lost a legend—and I lost a friend.

In a rich life that spanned humankind’s scaling of the heavens from Charles Lindbergh’s Atlantic crossing in a flimsy monoplane to tourists joyriding in space atop sleek rockets, Alexander Jefferson could proudly stake a claim as one of the begoggled pioneers who blazed an indelible trail in the sky. His dream of flight was born while growing up in Detroit and it rooted in Rouge Park, a sprawling green space on the city’s west side, where he delighted in slinging his hand-built model airplanes into the freedom of the open air.

He got to taste that freedom for himself after graduating with a chemistry degree from Clark College in Atlanta in 1942. By then, America was at war and desperately needed pilots. Along with nearly a thousand other African American men, he earned the coveted silver wings of an Army aviator at the historic air base in Tuskegee, Alabama.

A Combative Introduction to Combat

During advanced gunnery training at Selfridge Field near his hometown back in Michigan, he got a jarring introduction to the commander of First Air Force, Major General Frank O’Driscoll Hunter. In front of the assembled Black flyers, the World War I ace and Savannah, Georgia, native laid out an anachronistic and dispiriting view on race that included keeping the officers’ club segregated.

Sadly, it was neither the first nor the last of the wartime indignities endured by “Jeff,” as the pilots who knew him used to call their friend. In a conspicuous incongruity, he soon set sail for Italy to fight for liberty abroad while being denied its full fruits at home.

Jeff’s aerial exploits reached their climax over Toulon, France, on August 12, 1944. He bore down on a Nazi radar station in one of the red-tailed Mustangs of the 332nd Fighter Group, the all-Black unit led by the steely Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who exhorted his pilots to give their all. Braving intense enemy ground fire as he pressed the attack, Jeff stayed on his strafing run until his airplane erupted in flames, forcing him to bail out. After 19 missions, his combat days had ended; he was captured by German soldiers and held at Stalag Luft III. Later transferred to Stalag VIIA, he remained there until liberated by Gen. George Patton’s Third Army in May 1945.

Many years afterward, Jeff often visited the airport north of Detroit that my wife and I owned for more than three decades. It was fascinating when Jeff regaled us and our guests with stories of his prison experience. He enjoyed telling the part about how he was billeted in a certain barracks at his first prisoner-of-war camp at the behest of the senior-ranked prisoner.

Once inside the austere quarters, he found himself surrounded by other downed pilots and flight crew, who he described as “good ole white boys from the Deep South.” Incredulous, he looked at the barracks leader and asked, “Of all the newly arrived airmen, why did you select me to be a bunkmate?” Savoring the punch line and pausing for effect, Jeff quoted the senior officer: “We know there is no way you can be a German plant.”

For as long as the men shared a common fate as prisoners, they got along well enough. But, in an ironic twist that shed new light on historical stereotypes, Jeff singled out both camps’ German guards, saying that they had treated him “like an officer and a gentleman.”

After his liberation, he saw the nearby Dachau concentration camp. The unspeakable sights and unbearable stench imparted a lifelong lesson about the grotesqueries that certain individuals are capable of perpetrating if left unchecked.

Like the others serving overseas who had survived the travails of the world’s deadliest conflagration, he was elated to be going home. He had nothing but joy in his heart when the Cunard ocean liner that had been converted into a troop transport got within visual range of America’s coastline. Yet, when Jeff began to make his way off the ship by stepping down the gangplank to the pier, an Army private in the shore security detail called out to him with the n-word and barked the command to use a different exit ramp as he was on the one for whites.

Going to Work at Home

It was a rude awakening that the homeland’s racial attitudes and precepts had changed little if at all during his absence. Jeff and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen had set out to achieve the Double-V—victories against the twin evils of totalitarianism and racism. They had undeniably contributed to the accomplishment of the former, but the latter clearly required more time.

Indeed, three years later, in 1948, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the armed forces. It is not a stretch to say that the selfless service and extraordinary sacrifices of patriotic Black Americans in hostile skies and on scarred battlefields were among the factors that paved the way for Truman’s decision.

In turn, that giant leap forward in race relations fostered a change in societal views that shattered the barriers that had held back earlier generations of minority group members. Other civil rights breakthroughs followed, making opportunity and fairness more widespread. Despite this flowering of the Red Tails’ shared legacy, the sting of the pier-side incident regrettably ate at Jeff for the rest of his life.

Jeff left the active-duty Air Force in 1947 (retaining a commission in the reserves until 1969 when he retired as a lieutenant colonel). Because commercial flying jobs were closed to Blacks at that time, he assessed his prospects. He determined that his college education lent itself to his becoming a science teacher. For the next 30-plus years his lectures animated classrooms of the Detroit public schools where his fatherly discipline endeared him to his students.

The positive impact of his teaching career was on display at his 90th birthday celebration in 2011. Hundreds of his former students, mostly members of the Black middle class, came to pay their respects and Jeff greeted each by name as hugs were exchanged. Many brought their children and grandchildren to meet the kindly but demanding war hero who had mentored them. I was touched as the heartwarming scene unfolded. It spoke of a life well lived.

A Lasting Impact

Wanting to keep the history of his unique fighter unit alive, especially as a source of inspiration for young people, he and a small group of like-minded souls gathered in his basement in the early 1970s to plot a pathway for that future. The result was the creation of Tuskegee Airmen Inc., a national organization with the surviving veterans as the nucleus. A museum in Detroit was also established with activities that now include a youth flight academy at the city’s Coleman A. Young Municipal Airport (KDET).

Through the pirouettes of his life’s odyssey, Jeff’s enchantment with flight never waned. He co-authored a memoir and was featured in a documentary. His core message about attaining one’s dreams through perseverance was timeless. By overcoming obstacles to participate in a noble cause that involved personal risk, he proved anyone with the motivation and the training can succeed. The power of his example has changed skeptics into believers, observers into doers.

Coinciding with Jeff’s centenary in 2021, his hometown of Detroit rededicated a section of Rouge Park in his honor where a sign stating “Alexander Jefferson Field” marks the site until a plaza and statue are completed in the near future. The same grassy expanse where Jeff launched his model airplanes long ago continues to welcome youngsters to do likewise in the presence of a reminder of the would-be aviator who went on to fulfill his lofty dream.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox