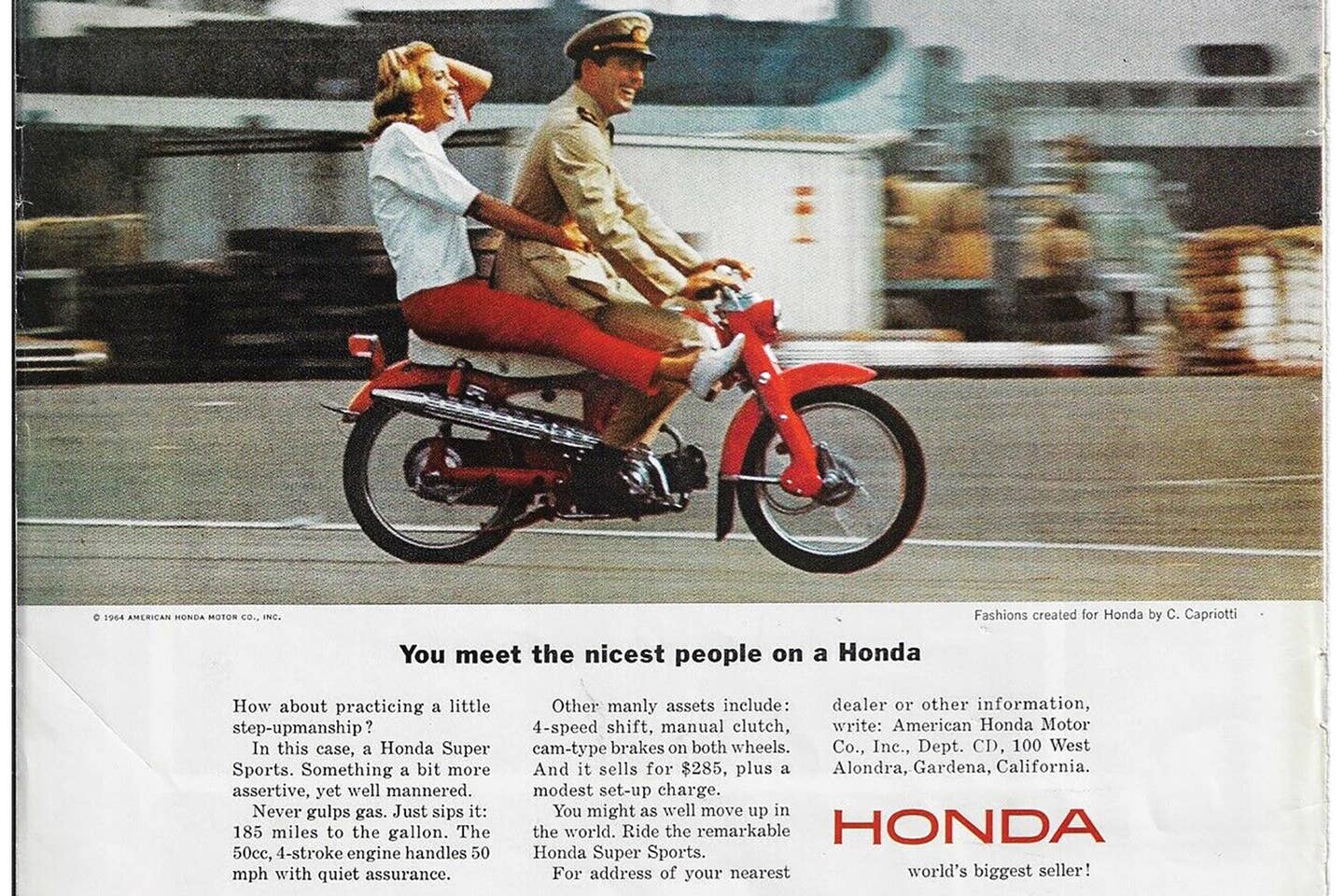

The author has met the nicest people in a Bonanza. Courtesy Honda Motor Company

I wasn’t looking for nice. I was a 14-year-old, eagerly flipping through a vintage Playboy magazine I found in a thrift store in upstate New York while my parents looked at an old rug in the next room. But still, the illustration—a carefree blonde, a man in uniform, both astride a Honda motorcycle carrying them forward out of frame—caught my eye. The girl, huge smile on, rode pillion with her arms wrapped around his waist. The ad promised a whole world of opportunity. I wanted in. Five years later, I bought my first motorcycle. I quickly found a community, fervent in their unique love for the sport. I thought I’d found my religion. But much later on in life, I found another, even more imperative subculture: aviation. Compared to motorcycling, aviation promises and delivers equally, minus the arms wrapped around you in flight. That would just be dangerous.

In my last 28 years of riding, nearly every motorcyclist I have passed has waved to me. I’m talking about a 95 percent rate of salutation here. No judgment either. Ducati riders wave at Harley bikers. Goldwings wave at Ninjas. It makes no difference so long as you are on two wheels. Pluralism in action. Imagine if every motorist you ever passed waved to you: You’d get carpal tunnel syndrome just trying to be polite. Why, then, do bikers all greet one another? It’s partly the diminutive size of the motorcycling population. By definition, you need small numbers for a subculture to exist. But beyond the census, an essential criterion is a unique love for the activity. The more fervent, the better. When the fervor approaches religion, you start waving.

Aviation is a religion. We as pilots possess the ardor. We have the dedication. We keep the faith (in our A&Ps at least). One could argue that any serious subculture has a religious quality to it. But what elevates aviation (and motorcycling to a degree) above your neighborhood ceramics club is the inherent risk. It may not feel like it to a competent pilot, but unlike pulling a car or bike over to the side of the road for a timeout, we pilots don’t have that luxury. An airplane in flight is coming down at some point, controlled or otherwise. No timeouts. That shared risk makes for a connected community. This is the house of worship I belong to.

When we meet another person who drives a car, we are not moved to conversation. “Wait, you also drive an automobile?” Yet any pilot can and will talk to another pilot at length. Politics and actual religion be damned. A crop-duster stick and an A380 captain will have plenty to discuss—because both abide by the same laws of aerodynamics. Our church cares only for lift, not useful load.

Beyond conversing, pilots maintain the ubiquitous quality of simply wanting to help. I experienced this firsthand when I flew my V-tail Bonanza across the country this past September. The first leg was from New York to Atlanta to have my esteemed mechanic, Bob Ripley, go over the plane. I completed a top-down restoration over the six months prior. When that many things have been touched, it’s best to have a good, long look by an expert third party, and in fact, there were a few omissions/discrepancies. We (well, Bob) corrected them, and I made my way west.

After landing in Monroe County, Mississippi, I walked into the FBO to find Cecil Boswell, a 77-year-old veterinarian who still regularly flies his Piper J-3 Cub. It was more than 100 degrees outside; neither of us were in any hurry to head back out. A few minutes later, his 89-year-old friend, Aero, showed up. Close friends since childhood, these two repeat this regimen five days a week. They meet at the FBO then saunter over a few hundred feet to their man cave: a corner T-hangar with its additional appendage converted into a little clubhouse. Aviation photos everywhere. TV on but no one watching. They don’t talk all that much as Aero can’t hear very well. But then, most of what’s needed to be said has already been said: the telltale sign of a lifelong friendship. I watched them drink vodka out of Styrofoam cups while they laughed a bunch. I abstained from the vodka but engaged wholeheartedly in the laughs. They hammered me with questions about my journey and regaled me with stories of their own flying adventures. When it got quiet, I explained I still had many miles to go.

Read More from Ben Younger: Leading Edge

As I stood up to leave, Cecil offered to show me Aero’s hangar. The sun was setting as he walked me over to a much larger hangar. Inside the dark, cool space was Aero’s own J-3 Cub: a yellow 1946 model in perfect condition. Aero can’t fly anymore, Cecil explained. He tried a few years back (with Cecil flying copilot) and realized he just didn’t have the faculty for it any longer. His time was up. I asked why Aero was holding onto the plane. Cecil shrugged. “He just likes to see it when he opens the door.” With no kids to inherit the Cub—Aero’s son died in Afghanistan flying for Blackwater, and his daughter recently died of pneumonia—who knows what will become of it. But I hadn’t detected any anticipation of that loss in Aero’s disposition. The man laughed and talked excitedly about all things aviation. You take hold of the joy wherever it comes, he seemed to say. And when able, you share it.

In the early evening, with the heat finally retreating, I took off for Oklahoma. Up at 10,000 feet, I asked for and received 30-degree deviations in both directions at pilot’s discretion. No, there weren’t any buildups. Just a benign collection of cumulus clouds floating up there like building-size cotton balls. They weren’t bumpy inside, and I was on an IFR flight plan. I could have easily just flown through them, but that wasn’t what this was about. I switched off the autopilot and made coordinated, swooping turns between the clouds, at times shooting small, wing-wide gaps. I felt Luke Skywalker levels of exhilaration. This is why kids want to be pilots when they grow up, I thought. The speed you normally have no sense of in cruise is revealed when passing a well-defined cloud 20 feet off your left wing at 184 ktas. See above for instructions on joy.

A night in Ada, Oklahoma, was followed by a short visit to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Halfway through my last preflight of the cross-country journey, I found the left aileron stuck in a full up attitude. I had moved the right aileron up and down with no resistance. But when moving the left, it froze solid. I went back inside the FBO. My dog, Seven, followed, euphoric that I had changed my mind about flying. I was not as excited. A stuck aileron is not a minor squawk. I made some calls, but this was a Saturday, so my hopes were not high for a result.

I was wrong. Thirty minutes later, I was watching Gerard Ontiveros from Santa Fe Aero Services climb up underneath my panel where he quickly found a ventilation hose that had come loose and become bound up in the aileron cable. “So that’s why there’s been no defrost heating,” I thought. Mystery solved. But also, lesson learned: Always preflight. The airplane was in a climate-controlled hangar overnight. Aside from a quick visual inspection for any hangar rash, one might think they could truncate the full preflight. But I did not. I went through every step, and thank God. If that aileron had frozen in flight (think 400 feet agl as I turned on course), it would not have been pretty. Not only did he save me, but Gerard refused payment. Flat out. I persisted—multiple times. He said he was just glad he caught it. I wished I had the Honda ad to show him.

Of all the departures I’d made crossing the country, this was the one I was most nervous about. By the time I was ready to depart, the density altitude was over 8,000 feet, and there were reports of low-level turbulence—conditions very similar to my crash in Telluride, Colorado, back in spring 2018. Nerves jangling, I called up Eric Eviston, my instructor, who is always happy to discuss things. It helped. Thankfully, the more I fly, the more opportunities I have to reciprocate for other pilots. When my friend Demian, a new pilot, calls to talk about New York (Class B airspace), it is no chore for me to spend 30 minutes on the phone, our charts open on both ends of the call, dissecting the sectionals with their esoteric markings. In this house of aviation worship, these are no less useful than scriptures—and, at times (certainly in flight), far more so.

Nerves calmed, I completed a near-perfect flight to Santa Monica, California, that afternoon where I began a 3-month-long work stint. I had been seeing slight traces of oil on the windscreen the whole trip, and my friend Howard pointed me to Kim Davidson Aviation to get it sorted; it turned out to be a leaky crank seal. When I went to see him, Kim walked out onto the tarmac and met me at the plane, his hand extended and a broad smile on his face. “Welcome to California,” he said, shaking my hand as if we’d been friends for years. He didn’t even know my name. All he knew was that we both love airplanes, and that was enough. You meet the nicest people.

Follow Ben Younger on Instagram: @thisisbenyounger

This story appeared in the April 2020 issue of Flying Magazine

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox