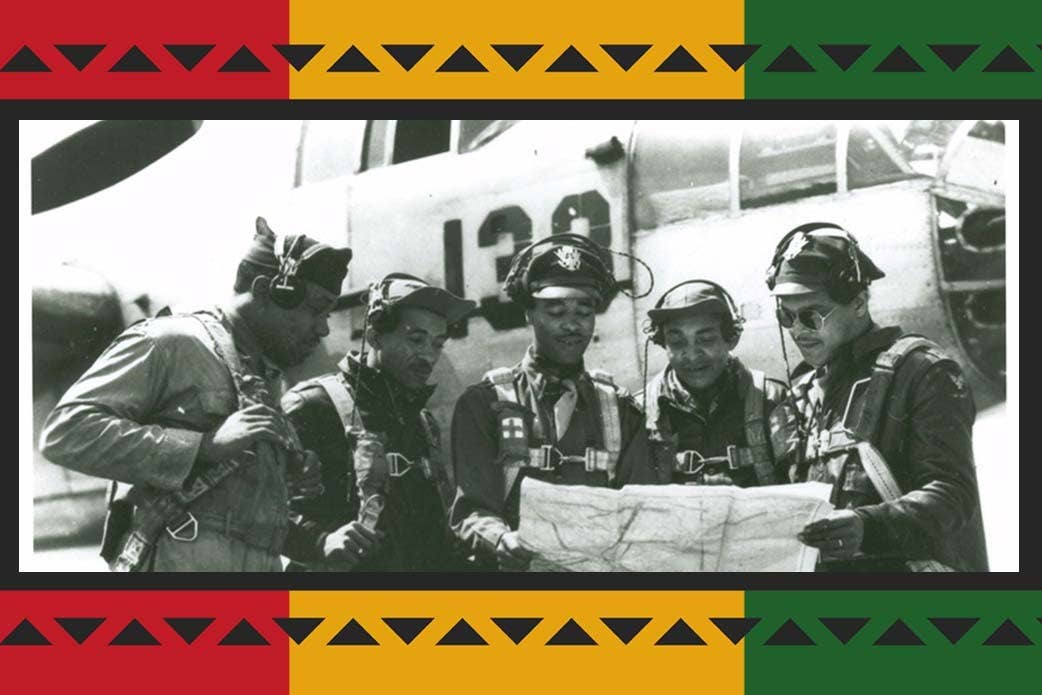

In 1941, the U.S. Army Air Forces formed the 99th Pursuit Squadron, a flying unit of Black pilots better known as the Tuskegee Airmen. [Courtesy: National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution]

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a month-long series celebrating Black History Month through aviation: Feb. 1: African American Pioneers in Flight and Space | Feb. 4: Legacy Flying Academy | Feb. 10: Why Aren’t There More Black Pilots in the Air Force? | Feb. 11: Jesse L. Brown | Feb. 15: Meet Four African Americans Making a Difference in Aviation | Feb. 18: From “Hidden Figures” to “Artemis” | Feb. 22: CMSAF Kaleth O. Wright | Feb. 25: Cal Poly Humboldt

This month, FLYING is marking Black History Month by celebrating the many accomplishments African Americans have contributed to aviation and space flight. Today we are exploring some of the top pioneers in U.S. aviation history whose experiences have created a legacy that continues to inspire a new generation of pilots, astronauts and engineers.

Eugene 'Jacques' Bullard

In 1917, at the age of 23, Eugene Bullard became the first African American combat aviator, however, it wasn't in the U.S. At a young age, Bullard left his home in Columbus, Georgia, and made his way to France, where he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion at the onset of World War I. He rose through the ranks, became decorated and following an injury during the Battle of Verdun, accepted an offer to join the French air force. While the original offer was to become a gunner, he received permission to train as a pilot. Bullard, along with about 200 other Americans, joined the Lafayette Flying Corps, flying combat missions until late 1917, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Following WWI, Bullard's military career was revived when at 46, he rejoined the French army when the Germans invaded the country in 1940. Following an injury from an exploding shell, he returned to the U.S., settling in New York, where he worked as a longshoreman.

"Bullard stayed in New York after the war and lived in relative obscurity, but to the French, he remained a hero," the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force said. "In 1954 he was one of the veterans chosen to light the 'Everlasting Flame' at the French Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe, and in 1959, the French honored him with the Knight of the Legion of Honor."

Bullard died in 1961, and he was buried with full military honors in the cemetery of the Federation of French War Veterans in Flushing, New York. In 1994, he was posthumously appointed a second lieutenant by the secretary of the Air Force.

The Tuskegee Airmen

While the U.S. military continued to reflect racial segregation, it would be the pressures of World War II that would officially open the door of opportunity for aspiring African American military aviators in the U.S. In 1941, the U.S. Army Air Forces formed the 99th Pursuit Squadron, a flying unit of Black pilots better known as the Tuskegee Airmen. The next year, Tuskegee Airmen were tapped for the newly activated 332nd Fighter Group, which would later consist of four Black fighter squadrons.

First lady Eleanor Roosevelt gave the newly formed Tuskegee Airmen a dose of good publicity when she visited the flight program and flew with C. Aldred Anderson, the African American chief civilian instructor.

During WWII, Tuskegee Airmen flew Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, Bell P-39 Airacobras, Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, and North American P-51 Mustangs, outfitted with an iconic red tail, rudder, and nose bands.

During WWII, Tuskegee Army Air Field turned out 650 single-engine pilots, 217 multiengine pilots, 60 auxiliary pilots, as well as five pilots from Haiti. The unit's first deployment was in North Africa.

The group is credited with flying more than 1,300 combat missions and destroying at least 40 boats and more than 160 enemy aircraft in air or on the ground, according to ourwwiiveterans.com. Their record garnered numerous military citations, including 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 14 Bronze Stars, eight Purple Hearts, and three Distinguished Unit Citations.

Bessie Coleman

Much like Bullard, Bessie Coleman was forced to look to France in order to get her pilot’s license, an endeavor that was sparked by a taunt from her brother John one day in 1919 as she worked as a manicurist in Chicago.

"John had served in the Army in France during World War I and often teased his sister about how women there had more opportunities. Women in France were so liberated, he said, they could even fly planes," the New York Times said in an obituary that honored Coleman in 2019. "Black 'women ain’t never goin’ to fly, not like those women I saw in France,'" he told her. Determined, Coleman learned French, and took jobs and asked for financial help. In November 1920, she enrolled in a seven-month flight school program in northern France.

In France and from the cockpit of a Nieuport Type 82 that boasted a 40-foot wingspan, Coleman learned how to perform aerial maneuvers. By 1922, she was performing across the U.S. "She dazzled spectators by walking on the wings while aloft or parachuting from the plane while a co-pilot took the controls. Her stunts were widely covered in the press, especially in black newspapers, and she cut a glamorous figure," the New York Times said.

Coleman was the first African American woman to earn a pilot license and is credited with inspiring future African American pilots. Her flying career was cut tragically short, however, when she fell to the ground from the cockpit of a military surplus Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" that had gone into a nose-dive and tailspin during a practice flight. Coleman, 34, was killed instantly.

Following her death, the Bessie Coleman Aero Club was opened in Los Angeles in 1929. The U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in her honor in 1995.

Cornelius Coffey

From a young age, Cornelius Coffey wanted to fly. In the mid-1920s, however, Coffey—who was studying to be an automobile mechanic—was denied acceptance into flight schools because of his race.

"Commercial flying schools wouldn't accept them, but a Black businessman lent the two a vacant storefront at 38th Street and Indiana Avenue, where they built a one-seat airplane powered by a motorcycle engine. They taught themselves to fly," the Chicago Tribune wrote in his obituary upon his death in 1994.

By the late 1930s, Coffey had opened his own flight school in south Chicago, the Coffey School of Aeronautics at Harlem Airport. Coffey's flight school was a center for Black aviation during the Depression, according to the National Air and Space Museum. The school was also instrumental in teaching Black WWII pilots as part of the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP).

Coffey is remembered as the first African American to hold a pilot certificate as well as an aircraft mechanic's license. "For almost 50 years, he helped open both occupations for Blacks," the Chicago Tribune said.

Willa Brown

Inspired by the legend of Bessie Coleman, Willa Brown was fascinated by flight and determined to fly. She learned to fly at Chicago's Harlem Field, where Cornelius Coffey was her certified flight instructor. (She and Coffey would later marry).

Brown played a "prominent role in Coffey's Chicago flying club, offering a role model for young African American women," according to the National Air and Space Museum.

"One day in 1936, wearing her striking white jodhpurs, jacket, and boots, she walked into the Chicago Defender newspaper office and made a professional pitch for publicity for an African American air show to be held at Harlem Field," the museum notes. "The advertising resulted in an attendance of between 200 and 300 people and showcased a number of talented Black pilots in the Chicago area."

Brown earned her master mechanic's certificate in 1935, but it was her achievement three years later that solidified her place in U.S. history. In 1938, Brown earned both an initial pilot's certificate and a commercial pilot's certificate, becoming the first African American woman to ever do so.

Her desire to open flight up to African Americans wasn't limited to the Chicago flight school, however. Brown lobbied for desegregation in the U.S. military, and under her leadership as director of the Coffey School of Aeronautics, the school was selected to offer the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) to train wartime pilots, a program that paved the way for training of Tuskegee Airmen.

Brown's legacy extended far beyond her place as the first African American pilot. She was also instrumental in helping to create what became known as the National Airmen Association of America, an organization formed to promote African Americans in aviation. She achieved the rank of Lieutenant in the Civil Air Patrol, becoming the first Black officer in the auxiliary arm of the U.S. Air Force. She ran for Congress. She also launched a tradition that still exists today: the annual flyover of Bessie Coleman's burial site in Chicago.

Robert Lawrence

Following the height of the Cold War, in the mid-1960s, the U.S. Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office launched a new program with one intention: to obtain photos of U.S. Cold War adversaries. The program was dubbed the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program and was to be executed by two-man teams living for 30 days at a time in mini-space stations in low polar Earth orbit.

In June 1967, Air Force Maj. Robert Lawrence was selected as an aerospace research pilot MOL, making him the first African American astronaut selected by any national space program.

“This is nothing dramatic. It’s just a normal progression. I’ve been very fortunate," he reportedly said at the time, according to NASA.

As an accomplished senior Air Force pilot, Lawrence accrued more than 2,500 flight hours, the majority of the time in jets. He also earned a Ph.D. in physical chemistry, making him the only MOL astronaut with a doctorate, according to NASA.

Six months after his selection, however, Lawrence was killed in a training accident at Edwards Air Force Base while flying an F-104 Starfighter supersonic jet.

"Because of his untimely death and the relative secrecy surrounding the MOL program, Lawrence's name remained largely unknown for many years," NASA said. In 1997, the Space Shuttle Atlantis crew took his MOL mission patch into orbit, and his name was engraved in the Astronauts Memorial Foundation's Space Mirror at Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.

In 2020, Northrop Grumman named its NG-13 Cygnus spacecraft in Lawrence's honor.

Guion 'Guy' Bluford

Aerospace engineer and astronaut Guion Bluford Jr. was 40 years old when he first went to space, marking his place in history as the first Black astronaut. By that time, the Pennsylvania native had been flying for nearly 20 years and already had a distinguished career in the U.S. Air Force, where he served as a fighter pilot.

In August 1983, NASA launched STS-8, its eighth Space Shuttle mission and the third flight of the Space Shuttle Challenger. The mission, which was the Shuttle's first night launch and landing, was to launch India's INSAT 1-B communications satellite and also conduct the first tests of Shuttle-to-ground communications. Crew members were also tasked with exercising the Remote Manipulator "arm" with a test article weighing nearly four tons, NASA said.

During the mission, Bluford became the first African American in space. It wouldn't be his last trip.

"As an astronaut, Bluford worked with space station operations, the Remote Manipulator System, Spacelab systems and experiments, space shuttle systems, payload safety issues and verifying flight software, and flew on three more shuttle missions—STS 61-A, STS-39 and STS-53—logging over 688 hours in space," NASA said.

Dr. Mae C. Jemison

Dr. Mae Carol Jemison has degrees in chemical engineering, African and African American studies and medicine, but it was the Nichelle Nichols' Star Trek character Lt. Uhura that first turned her imagination to space, she once said.

"As a little girl growing up on the south side of Chicago in the ’60s, I always knew I was going to be in space," she said at a conference at Duke University in 2013.

In 1992 and as part of STS-47's Spacelab J—the 50th Space Shuttle mission and the second for shuttle Endeavor—she did just that, becoming the first African American female astronaut.

"On her first flight, she was the science mission specialist on STS-47 Spacelab-J. The mission, which was a cooperative one between the U.S. and Japan, included 44 life science and materials processing experiments. Jemison was a co-investigator on the bone cell research experiment flown on the mission. In completing her first space flight, Jemison logged 190 hours, 30 minutes, 23 seconds in space," NASA said.

Not long afterward, art imitated life when Jemison made an appearance on the Enterprise's bridge as Lt. Palmer in a guest appearance on Star Trek: The Next Generation. Nichols, who played Uhura, visited her on set, the Smithsonian magazine reported.

Following her work with NASA, Jemison started a medical company, taught at Dartmouth College and Cornell University, authored several children's books and founded the Dorothy Jemison Foundation for Excellence educational nonprofit. Jemison's accomplishments were also commemorated by Lego, which released a minifigure of her as part of its "Women of NASA" set.

The 'Hidden Figures'

Perhaps no story embodies the struggle of race and gender in the world of space exploration as powerfully as that of the real-life "Hidden Figures" Katherine Johnson, Mary W. Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan. The three African American women are credited by NASA as essential to the success of early space flight.

Johnson, a mathematician and Black public school teacher, was hired by NASA in 1953 when she was selected for a position at the segregated West Area Computing section for NASA's predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics' Langley laboratory. Following a temporary assignment, she began analyzing flight-test data.

Johnson did trajectory analysis for Alan Shepard's Freedom 7 mission in 1961, and co authored a report outlining equations for an orbital spaceflight in which the landing position of the spacecraft is specified. In 1962, her work on John Glenn's orbital mission illustrated how pivotal her work had become to the space program.

As a part of the preflight preparations, Glenn asked for Johnson to calculate orbital equations by hand as a check of computer calculations. 'If she says they’re good,’ Katherine Johnson remembers the astronaut saying, 'then I’m ready to go.' Glenn’s flight was a success, and marked a turning point in the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union in space," NASA said.

Mary W. Jackson overcame segregation and gender bias to become NASA's first African American female engineer. She began her NASA career as a human computer at Langley, and later conducted hands-on experiments that helped pave the way for her to become an engineer. “Mary W. Jackson was part of a group of very important women who helped NASA succeed in getting American astronauts into space," former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said. "Mary never accepted the status quo, she helped break barriers and open opportunities for African Americans and women in the field of engineering and technology."

Dorothy Vaughan began her NASA career as the first African American female supervisor for the segregated West Area Computing section. In 1958, when segregated units were disbanded by NASA, she joined the integrated Analysis and Computation Division, where she became an expert FORTRAN programmer.

"She challenged herself to learn new technology so that NASA could have the very latest computing technology for research applications. Her countless calculations supported NACA and NASA accomplishments and helped to achieve the nation’s aerospace goals from the early days of World War II to the beginnings of the Space Age," NASA said. "She persevered to serve her country when many would hold her back because of her race. After her retirement, when asked about working within the constraints of segregation and gender she remarked, 'I changed what I could, and what I couldn’t, I endured.'"

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox