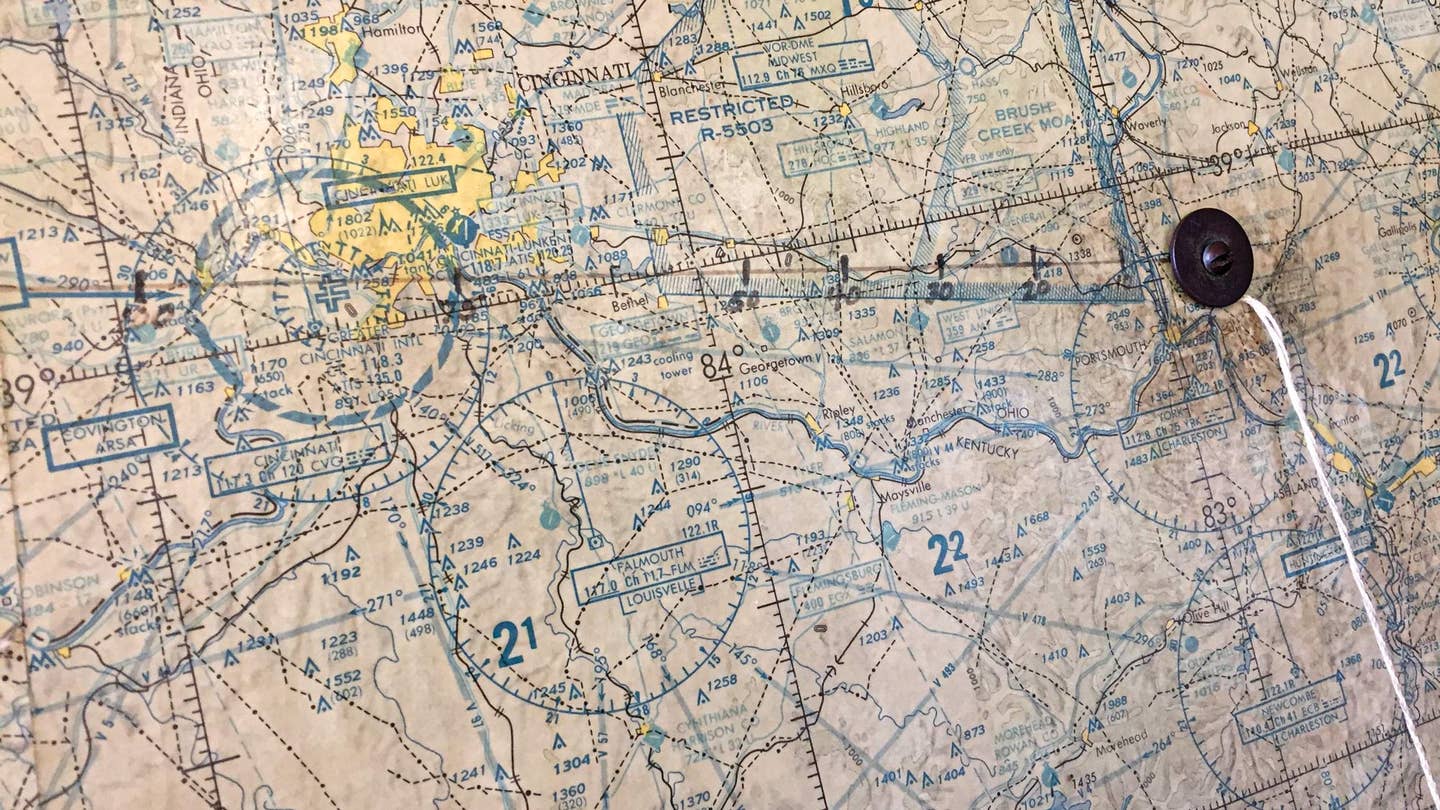

Pull the string to measure the distance you’ve come, or discover where you are. Courtesy Martha Lunken

This feels a little bit too much like going to confession, but I’m going to come clean and admit I’m a paper-chart girl. Always have been, always will be. One of those rare, soon-to-be-extinct dinosaurs who still subscribes to printed charts. But before your jaw drops any farther, it might help to know I’m not exactly a purist. I love those Garmin boxes in my Cessna 180—a WAAS-enabled, IFR panel-mount GPS and a 696 portable with SiriusXM weather. And then there’s the ForeFlight app on my iPad and iPhone. But in spite of all this electronic wizardry, I wouldn’t dream of slipping the surly bonds without IFR en route charts, bound paper approach plates and those beloved sectional charts in my airplane. And, yes, I use them flying VFR or IFR or both…well, maybe not the en route charts much anymore.

But you can’t open an aviation magazine or visit a website without being bombarded with ads for the newest, ever-more-sophisticated electronic wizardry. So I’ve been chewing on my obsession with paper and the habit of looking for and identifying visual ground references—when I can see the ground. Sure, I know you can display a VFR chart on the GPS or iPad. With ForeFlight, for example, the electronic maps can be even more useful if you know how to customize them, selecting more-useful terrain, airport or waypoint features—and lots and lots of other stuff.

But, therein, for me, lies the problem. To effectively and safely use ForeFlight, Garmin or Jeppesen apps on an iPad, you have to be intimately familiar with their huge capabilities and comfortable with navigating between screens to pull up needed information. Using it while flying IMC demands no “noodling around,” no hesitation in selecting which of the small and (to me) nonintuitive buttons to push. And—this is critical—you need at least a semistable platform and finger dexterity to select the right ones.

In my beloved old Cessna 180, I have to strap the mini iPad to my knee because there’s simply no place in the cockpit to mount a larger device. And while my hands do work—after a lifetime of broken fingers, crushed knuckle joints, botched tendon surgery and arthritis—they’re kind of a mess. Flying single-pilot IFR with no autopilot, using the iPad means peering down into my lap under the yoke to enter or retrieve information on those tiny buttons while depending on trim and smooth air to stay on altitude and heading. It’s beyond challenging—it just doesn’t work. But with the other installed boxes, it isn’t necessary. So I use the iPad and iPhone for preflight planning and filing…period.

Yesterday, I was in desperate need of an airplane fix after a trip that necessarily involved eight hours in a car, driving between southern Ohio and northern Michigan. ForeFlight told me the weather was great, so I tugged the 180 out of the hangar, fired it up and tried entering the identifier of a private strip about 50 miles east in “direct to” on the GPS units. It wasn’t in the database of the Garmin 430 but did appear in the 696.

Then I thought: “Oh, hell, let’s do it the old-fashioned way.” I pulled the sectional from the side pocket and eyeballed a bearing from Lunken Airport to the destination strip by paralleling a bearing off the CVG VOR azimuth. I picked up that heading plus 5 degrees right for the wind, estimated from the speed and direction of cloud shadows moving across the ground. I tuned in a VOR out that way and set the OBS to what looked like a good cross bearing over the strip. From there, it was just dead reckoning and pilotage—picking up lakes, little towns and even a drive-in movie theater as ground references. And, in this glorious 1960s time warp, I ended up right over my friend’s strip.

But, curiously, I found myself defending, or trying to justify, navigating without all the boxes running. Good practice for an electrical-system failure? C’mon, an alternator failure with simultaneous battery deaths in a 696, iPhone and iPad? OK, more likely a reversal of the earth’s magnetic poles (due to happen again, by the way, in the next few thousand years). Finally, I just basked in the fun of it, the way I—and a lot of you—learned to fly: with carefully plotted courses and checkpoints marked on the sectionals. That fairly new, high-tech VOR thing was an awesome aid but kind of like cheating.

Read More by Martha Lunken: Unusual Attitudes

Remember when every airport had one wall papered in sectionals with a string anchored at home base? Pulling the string to your destination—maybe nearby, maybe clear across the country—you read the course from an azimuth and distance off the mileage scale. And remember all the places you’d go…some for real, others to dream about for “someday.” And if you were a bit uncertain (lost), seeing where that string started sure beat asking somebody where you’d landed.

There are other uses. My friend Barry Schiff remembers his instructor smacking him on the back of the head with a rolled-up chart when he was learning to fly in an Aeronca Champ. These days, that’s not an approved FAA learning procedure and deemed traumatic by psychologists. Balloonists taught me if you cover a sectional in clear Contact-brand shelf paper (not the real-sticky kind), it’ll last forever—also not an FAA-approved procedure. Charts make great sunshades, and I’ll admit to, like Captain Schiff, using one as an improvised instrument hood. But he says, and I heartily agree, “Every pilot should have a Plan B, and ‘B’ means back to basics, which to me means having paper charts in the cockpit.”

So I’ll keep stashing my paper charts and books in Victoria’s Secret bags and add to my shutdown checklist: “Secure paper charts out of sight.”

A pilot friend (is there any other kind?) recently sent an unusual, beautifully handcrafted and—for me—highly appropriate card. It’s fashioned with a small piece of a sectional chart and bordered with the mileage scales found on the edges of those charts. And on the face is this quote from pilot and author Beryl Markham’s well-known West with the Night:

A map in the hands of a pilot is a testimony of a man’s faith in other men…

A map says to you, “Read me carefully, follow me closely, doubt me not.”

It says, “I am the earth in the palm of your hand.

Without me, you are alone and lost.”

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox