Cincinnati Will Always Be My ‘Home Sweet Airport’

Lunken Field faces an uncertain future, but it will forever be a special place.

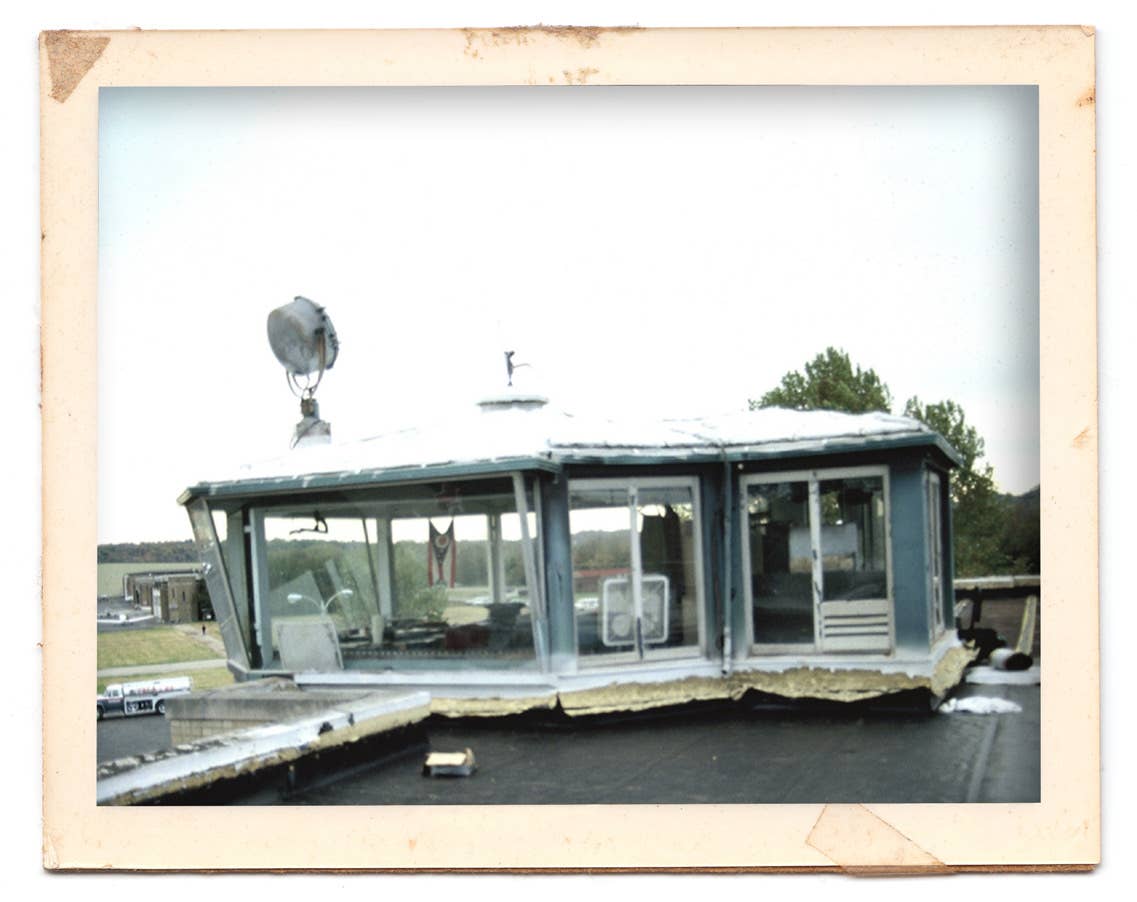

The original FAA control tower in the terminal building at Cincinnati’s Lunken Airport sits in a state of disrepair. [Courtesy: Martha Lunken]

I had lunch with some pilot friends, including a retired airline guy, a kid working two jobs and going to college—crazy about learning to fly—and two or three others who can fly or fix anything from sophisticated corporate jets to homebuilts and small, antique taildraggers.

It’s great to call them friends, but the conversation topic was grim: “What in the hell is going on at Lunken Airport?” Sure enough, the front-page headline in the Sunday Cincinnati newspaper shouted, “What’s Next for Lunken Airport…Cincinnati’s tiny, aging airfield…and what’s ahead for the struggling airport’s second century?”

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe Now“Aging”? OK. “Struggling”? I don’t think so. Mismanaged? You bet!

After the inevitable COVID-19 pandemic slowdown, Lunken general aviation and corporate traffic recovered dramatically. Recently there have been 10-to-15-plus jet operations each hour and an increase of 100,000 total operations in each of the past two years. Three thriving flight schools, plus private and corporate traffic, keep the control tower busy from 0700 to 2300 local time every day.

But the city is tearing out one of three runways—the oldest one that’s parallel to the primary, 6,100-foot 21L-02R. It has multiple functioning instrument approaches, lighting, and markings, but eliminating 21R leaves only a shorter runway, 7-25, which is unusable for airplanes over 10,000 pounds. gross weight and whenever the long runway is active because of crossing approach paths.

- READ MORE: An Ode to Aircraft Mechanics

Cincinnati Municipal Airport-Lunken Field (KLUK) has long been home to large and small corporate flight operations with multiple business aircraft, including Procter & Gamble (on the field since 1950), Kroger, NetJets/Executive Jet Management, American Financial Corp., and more. These days there are more smaller jets and turboprops (Pilatus, TBM, etc.) that increase jet light turbine operations to about 250 daily.

The flight schools are seeing unprecedented growth with student pilots flying for fun or business and many pursuing airline careers. Lunken Flight Training, a Part 141 school, occupies two of the original three brick hangars built for the Embry-Riddle Company in 1927, and it’s swamped with students and renters.

Years ago, Cincinnati Aircraft was where I launched my 6,000 hours of instructing and, much later, was a busy DPE. Jay Schmalfuss (c’mon, Cincinnati is a German town) has turned it into an impressive operation. Sitting in on one of its weekly huddles, I learned operations have risen 30 percent this year, following a 30 percent increase the year before. Its fleet includes 10 Cessna 172s and four Diamonds with more on the way.

The FAA and the city also continue to demand that one of those three historic hangars be demolished because of its proximity to the Runway 25 takeoff area. This once beautiful, abandoned building has badly deteriorated—sad to watch. This most ornate of the three hangars has lasted for nearly 100 years with nobody crashing into it. From the ’50s through the ’80s, it was the place to learn to fly or keep your airplane. The exterior was classic art deco, and the interior offices were elegant, like something out of a movie.

That art-deco terminal building—also now abandoned–was built with Works Progress Administration funds in 1936 and ’37. Flooding had been a danger (hence the nickname “Sunken Lunken”), but pumps, levies, and other flood-control measures tamed that problem from the adjacent Ohio and Little Miami rivers.

- READ MORE: Perusing Some Old Logbooks

The terminal’s beautiful lobby had a number of ticket counters for scheduled airlines when Lunken was once the city’s main airport and the world’s first and largest municipal facility. In the ’30s, American Airlines based at Lunken and operated schedules with Curtiss Condors and DC-3s. American opened its original Sky Chef restaurant in the building.

But after World War II the search was on for a larger airport. Federal funds were available, and across the Ohio River in northern Kentucky, a military field had been built during the war. Alben Barkley was a Kentucky Democrat and vice president under Democrat President Harry Truman, while Ohio was a solidly Republican state. So, it’s no mystery why the “Greater Cincinnati” airport was built on that property near Covington, Kentucky (thus the “KCVG” designator), and the major airlines abandoned Lunken for what is now Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International.

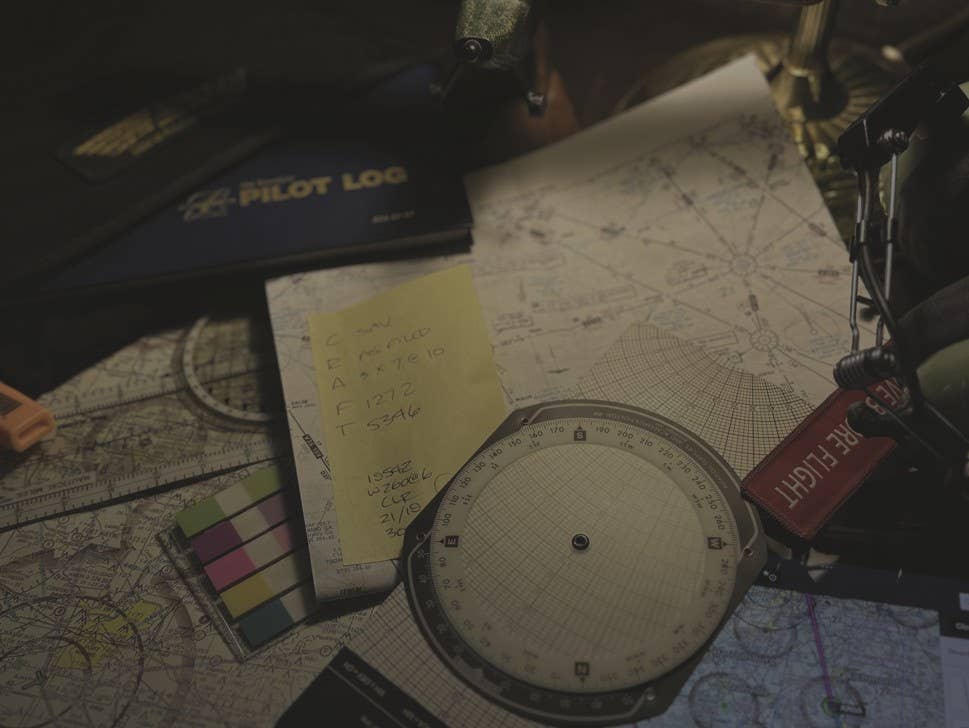

When I came to the airport in the early ’60s, the terminal building housed the control tower as well as a Flight Service Station, offices, the Airman’s Club, and the Sky Galley (once Sky Chef) restaurant. Any night of the week, the restaurant was crowded with airport and nearby racetrack people. The food was pretty good, and the bar was always jumping.

I met Ebby Lunken there, we got engaged, and I worked for his Midwest Airways while getting private, commercial, and instructor ratings. When the little airline closed, Ebby moved to a second-floor office, and I played secretary to his (pre-Part 135) charter operation, booking trips on his DC-3 and Lockheed 10s in the mornings (and climbing out a window to tend a thriving herb garden on the roof). Afternoons and evenings, I flight instructed and eventually opened my own school.

I’m no expert on city politics, but I’m pretty sure the City of Cincinnati knows as much about airports as I do about quantum physics. They hired a commission which recommended the airport needs to generate between $8 million and $27 million, and a new manager whose main qualification is he’s always loved airplanes and is “anxious to do whatever the city wants.”

So, all hangar rents have increased at Lunken Airport, and I have to get rid of the 1942 John Deere tractor stored in my hangar for a corporate pilot friend. That’s fair enough, but with Runway 21R gone and corporate hangars (no T-hangars) extending out into the middle of this essentially one-runway airport, the impact on us little guys and student traffic will be devastating. You can’t easily insert touch-and-go traffic between frequent jet operations.

I wonder if all the fences and locked gates installed after 9/11 are the real reason that no bombings or hijackings have occurred at Lunken or any other GA airport. But sadly there’s no curious teenage eyes peering through to learn about flying anymore.

Have we surrendered too much freedom to government mandates? Painfully, the Lunken Airport I’ve known and hung around for 62 years is becoming something very different. I’ve flown, loved, laughed, cried, crunched a few airplanes, and made countless friends at this old place. I’d sit in the control tower on crummy days and, even now, they call me by name.

I taught hundreds of people to fly and issued licenses to hundreds more from this field. It’s a special place that will always be my “Home Sweet Airport.”

This column first appeared in the September Issue 950 of the FLYING print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox