** To see more of Barry Ross’ aviation art, go

to barryrossart.com.**

Two business associates and I were on the second leg of a three-leg business trip that would carry us from Chino, California, to Las Cruces, New Mexico, to Boulder, Colorado, and then back home. The first leg was one I had made on numerous occasions because my company had several customers in the New Mexico area. To this day I can mentally recite all the navigational aids and waypoints (in order) to get to Las Cruces, El Paso, Texas, or Alamogordo, New Mexico. On an afternoon in late January 2000, after a couple of days of business meetings at White Sands Missile Range, we returned to the Las Cruces International Airport (KLRU). The weather that day at KLRU was beautiful, not a cloud in sight. A telephone weather briefing for our approximately 500 nm trip raised no concerns — clear with moderate winds aloft. There were no forecast weather problems between Las Cruces and Jeffco — the Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport (KBJC) in Denver, our destination. When transitioning a busy traffic area such as Denver I usually file IFR, so after lunch and a thorough preflight we departed, having filed for 11,000 feet.

Based on what we could see and buoyed by the favorable weather briefing, we anticipated an uneventful trip. We sat back to enjoy the spectacular New Mexico scenery as we headed north toward Socorro. The first indication of what lay ahead occurred as we turned northeast to cross the Sandia Mountains just south of Albuquerque. We've probably all experienced that moment in flight when the airplane takes on a different feel. We can't explain why and we can't pinpoint the reason, but the pilot/control interface gives a strange sensation. When this moment occurred for us, I told my passengers to buckle up tight as I expected we were in for a special ride.

As we neared Las Vegas we started to experience moderate turbulence: uncomfortable, unforecast, but not unexpected in this area in the late afternoon. We were just acclimating to the bumpy ride when the turbulence suddenly changed from moderate to severe. Now the weather had our attention. I became more alert and sat more erect in my seat. Soon we entered a mountain wave the likes of which I had never experienced before, nor have I experienced it since. Now in full attention mode I told my back-seat passenger to pull out the portable oxygen tank and cannulas just in case we ascended, either willingly or unwillingly, into the oxygen mandated altitudes. Even though I was straining to maintain my best pilot cool, I'm sure my voice reflected the tension I felt as I asked ATC for a block altitude. To my great relief and surprise the controller quickly cleared me for any altitude between 11,000 and 17,000 feet. I'd never received such a large block. It was as if he had a premonition of what we were about to experience. As it happened, before the wave finally spit us out, we had used every single foot he had given us.

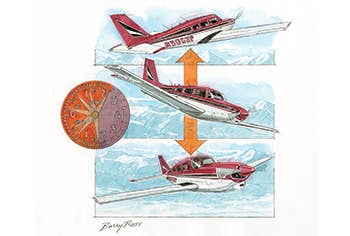

We quickly donned oxygen. While in the wave we ascended straight up as if we were on a high-speed elevator. Then our stomachs gave warning that we were about to descend at an equally fast rate. Over and over again this sequence was agonizingly repeated. Within these cycles we pitched up, we pitched down. We violently yawed left and right. We dropped our left wing and then our right. With our warped sense of time all of these excursions seemed to occur simultaneously. It was as if we were in the grasp of some gigantic hand, the possessor of which was trying to violently shake us out of the airplane. I was just holding on, along for the ride, not at all certain of the outcome. Would my faithful Comanche with which I had shared so many grand adventures and which had taken me so many places hold together through this seat belt stretching, teeth clenching, roof thumping ride?

For the nearly 125 nautical miles from Las Vegas to Colorado's La Veta Pass we endured this violence. I could look to the left and often in our wild excursions see the Sangre de Cristo Mountains seemingly well below our altitude. How far to the east and how high did we have to go to escape their grasp? Suddenly, just north of the entrance to La Veta Pass, the turbulence and updrafts and downdrafts ceased just as quickly as they had begun. My right-seat passenger and I managed faint smiles but we braced ourselves, at least mentally, for the next anticipated onslaught.

After a period of relative calm I decided it was finally safe to descend to our filed altitude and remove the oxygen. I communicated our current condition to ATC. I could finally relax; I could finally breathe again. I slumped in my seat, releasing my death grip on the yoke. At first I stared straight ahead, in a state of shock, reliving the last 45 minutes. Then I looked over at my right-seat passenger; he was ashen in color. He could not even muster a response when I inquired as to how he was doing. He would maintain that status for the remainder of our trip. My back-seat passenger jumped into the awkward silence with the unsolicited opinion that what we had just experienced was fun. I made a mental note; from that point on I needed to doubt his opinion and sanity.

The rest of our trip to Jeffco was relatively uneventful. But anything would have seemed benign after what we had just survived. After we landed and taxied to parking, I think we all deplaned — even the crazy guy in the back seat — with a new appreciation for terra firma.

Two days later we departed Boulder early on a cloudy, windy morning to return to California. I could get my right-seat passenger back into the airplane only by promising we would not experience anything like we had before. It was a promise I was not sure I could keep. My intent was to fly as directly as possible to Chino Airport (KCNO). But ice-filled clouds covered the Rockies to altitudes beyond my Comanche's capabilities, preventing this. Even La Veta Pass was not passable because of icy cloud buildups. So we continued farther south, eerily retracing our previous trip, finally turning to the west near Las Vegas. Surprisingly, our return flight along the Front Range was relatively smooth, devoid of even a trace of the turbulence and updrafts and downdrafts we had endured two days earlier. However, when we finally turned west we were greeted by 50- to 70-knot headwinds. Go figure. Our one-stop trip back to California seemed to take forever.

As the title of this column says, I learned about flying from that. In the summer, a few years later, my wife and I were returning from a weeklong family visit to Chicago. On the first day we had flown from Chicago to Dodge City, Kansas, stopping early in the day to wait out cumulus buildups along our route. The following day we intended to continue through southern Colorado to a refueling stop at the Grand Canyon and then on to our home base in Chino. It would be a long day of flying, but after a good night's sleep we both felt we were up to it.

The weather briefing I received predicted good visibility beneath a high overcast with fairly favorable winds aloft. We departed Dodge City early in the morning, anxious to get home. Just southwest of Pueblo, Colorado, at the entrance to La Veta Pass, I experienced the same pilot/control interface sensation that prefaced the previously described harrowing experience. I queried ATC about ride reports through the pass. Without hesitation she responded that the few airplanes that braved the route earlier reported severe turbulence and large updrafts and downdrafts. The situation sounded too familiar. After very little deliberation I told the controller I was going to do a 180 and land and stay in Pueblo that night. She concurred that I had made a good decision. I felt validated because it was one of the few times I had ever heard a controller express an opinion regarding a weather decision I'd made during flight.

The next day we departed Pueblo for Chino. We experienced light to moderate turbulence through the pass but nothing like we would have encountered a day earlier. We proceeded home via the Grand Canyon, comfortable with the decision we had made.

Yes, we can learn from previous experiences, especially if the experience has been etched on our brains.

Get online content like this delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for our free enewsletter.

We welcome your comments on flyingmag.com. In order to maintain a respectful environment, we ask that all comments be on-topic, respectful and spam-free. All comments made here are public and may be republished by Flying.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox