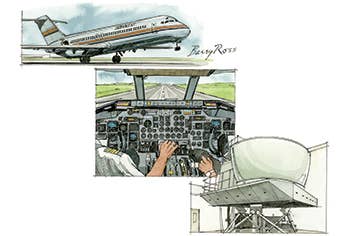

I Learned About Flying From That: From Glass Cockpits to Steam Gauges

** To see more of Barry Ross’ aviation art, go

to barryrossart.com.**

I adjusted the captain’s seat a final time and exhaled a hushed whistle. My eyes darted across the DC-9’s cluttered instrument panel. Endless dials and knobs were embedded in the gray metal. A seasoned DC-9 pilot would view the layout as a smile from an old friend. I felt like I was shaking hands with a stranger that had been crisscrossing the skies for decades. When the DC-9 first flew in 1965, I wasn’t even a blip on its green-and-black radar screen. The aircraft’s impressive production run was nearly over by the time I was born.

This meeting between old and (somewhat) young continued as I reached up to the overhead panel, my fingers brushing against the DC-9’s beefy switches and square blue lights. The faded white labels etched into the blackness around them were a timeless guide to operating this classic.

The introduction concluded with me lightly tapping the attitude indicator. Gone were the colorful EFIS tubes of modern aircraft, the prominent and centralized FMS computers preceded by bulky radio knobs. GPS and moving maps weren’t even a glint in the DC-9’s windscreen. The 10,700-foot runway beyond wasn’t electronically displayed — it was simply the way skyward where the DC-9 was most at home.

I lightly gripped the paint-chipped yoke with my left hand and gently placed my right atop the thrust levers. I eyed the rectangular master warning and master caution lights, half-expecting them to illuminate as the DC-9 sensed my unfamiliar touch. Turning to my friend Matt Pieper in the right seat, I asked, “Are you ready? Shall we see if we can fly this thing?”

“Absolutely,” Matt grinned.

“Alright, we’ll proceed as briefed.”

I scanned the instruments and looked toward the runway’s end. The cockpit floodlights contrasted with the gray overcast lingering 200 feet above. My feet slid off the brakes and down to the rudder pedals. Slowly, I nudged the thrust levers forward. The clocklike engine instruments edged upward and the Pratt & Whitney JT8 engines’ whine cycled higher.

“Here we go,” I half yelped as I pushed up the throttles. “Set thrust.”

Matt’s left hand guided the twin levers toward our target setting, but the DC-9 continued crawling along at near idle thrust. It seemed to move when it was ready. Several seconds later, seemingly satisfied, the JT8s spooled to a muffled roar. I was pushed against my seat as we accelerated. Imperceptible rudder pedal pressure kept the DC-9 tracking centerline.

“Thrust set,” Matt said.

I placed my hand back on the throttles. The nose wheels below the cockpit thrummed against the pavement as they picked up speed.

“Eighty knots,” Matt called.

“Checks.”

The runway’s distance markings began passing quickly, white flashes disappearing beneath the DC-9’s venerable wings. My brow furrowed as the time to abort our flight narrowed.

“V1,” Matt announced as we exceeded takeoff decision speed. My right hand moved to the yoke’s other worn grip. We were committed — there was no turning back now.

Then a few seconds later: “Rotate.”

I eased back on the yoke and grinned as the DC-9’s nose slowly and smoothly lifted off the centerline. The runway’s pavement steadily fell away as gray sky enveloped the windscreen.

The control forces were a mixture of balance: heavy but responsive, stiff but stable. Their sturdiness felt wonderful in my hands.

“Positive rate,” Matt announced.

“Gear up.”

I centered the aircraft at 15 degrees of pitch on the attitude indicator. The airspeed and altimeter needles pointed faster and higher. When the cockpit darkened seconds later, the DC-9 was engulfed in cloud; its landing lights reflected the gloom. As the JT8s pushed us deeper into the grayness, I hoped their whine wasn’t a horrid protest. Exploring an unfamiliar aircraft on the ground was acceptable; taking it airborne was another matter.

Matt and I weren’t rated in the DC-9 and had never received training in the type. Perhaps most glaringly, our careers involved only aircraft with computerized glass instruments displaying airspeed trend vectors and GPS maps that redefined the term “situational awareness.” The DC-9’s steam gauges indicated only essentials. Pilots rely on traditional instrument scans and mental math to calculate time, speed and distance. If issued an altitude crossing clearance, a DC-9 driver would mentally compute the required descent rate; I would reach for the FMS keypad.

My eyes strained amidst theses differences. Looking at the DC-9’s panel was like scrutinizing a newspaper’s fine print. I glanced at the master warning and caution buttons. They remained dark, but they felt like two angry eyes watching me, appalled that I had taken the DC-9 aloft.

Fortunately, this experience occurred in a simulator — not an actual DC-9. The device is owned by ABX Air Services at Wilmington Air Park in Ohio. ABX Air no longer operates the DC-9, but it still provides the simulator to companies flying the aircraft. Ironically, the “box” is practically brand new. Manufactured in 2003 as a DC-9-30 model, it utilizes the latest in simulation technology.

I had always wanted to fly this distinguished aircraft. As I manipulated its yoke, I imagined the thousands of airmen that had coaxed the DC-9 across time. Pilots that flew the aircraft in the 1960s may have grandchildren piloting it today. If only for a while, it was gratifying to experience the DC-9’s history — a durable link between aviation’s past and present.

Yet I had some questions: How well could two EFIS pilots fly the DC-9? How difficult is the transition from automated cockpits to flight decks devoid of technology? Would our instrument scans be adequate to fly the aircraft “raw data” — the flight directors buried within the DC-9’s panel?

When I trained 12 years ago in the CRJ, my first glass airplane, the instructor insisted that going from steam to glass was easy. Returning to steam from glass, though, was like sending an email through a telegraph. I currently fly next-generation Boeing 737s, and Matt pilots Embraer 145s. Both have glass cockpits. We were going to learn if the instructor was correct.

Matt and I tried to prepare. We discussed what calls to make and checklists to utilize. We spoke with my friend Joe Seymour, a former DC-9 instructor pilot who provided various details concerning pitch and power settings and approach profiles. We reasoned this expertise and our briefings would suffice. They certainly helped; however, the DC-9 had other plans.

“Where are we?” I asked. After some air work, we prepared for Wilmington’s ILS 22R. My basic attitude instrument flying was acceptable, but there was a problem: We were lost.

“We’re on a right downwind,” Matt replied.

“So we’re past the airport?”

“I think so. Stand by.”

When the DC-9’s trim switch is held for three seconds, a loud buzzing occurs to remind the pilot of the horizontal stabilizer’s movement. It could’ve also signified disgust at our lackluster situational awareness. Spoiled by GPS maps, we struggled to interpret the DC-9’s indications. I pulled my thumb off the electric trim.

Eventually, Matt tuned the nondirectional beacon that was the ILS’s outer marker. The ADF needle on the small radio magnetic indicator swung directly to the right. “We’re abeam the outer marker.”

“Flaps 5, please. We’ll start slowing.” I glanced at the radio magnetic indicator, having completely ignored it in my scan. The instrument was obsolete in modern cockpits yet pivotal in the DC-9.

We continued toward the approach. When established on the localizer, we configured to Flaps 15. The DC-9 responded well to subsequent pitch and power changes. The trim buzzer sounded, but it was expected as my thumb jabbed forward. Matt and I tried to determine if we needed any wind correction. While EFIS cockpits display wind direction and speed, the DC-9 makes its pilots derive their own crabbed headings.

When the glideslope came alive, we extended the landing gear and the flaps to 25 degrees. When the diamondlike symbol centered, I called, “Flaps 40, final items.”

As we slowed to our approach speed of 135 knots, I advanced the thrust levers to maintain speed. The DC-9 settled into its final approach attitude, its nose held high. Minor control inputs kept the localizer and glideslope centered, the needles familiar constants in the time-frozen panel.

“Five hundred feet above ground,” Matt said as we slid down the glidepath. The clouds stubbornly remained. “Slightly left of course.”

“Correcting.” The DC-9 was nimble during all phases of flight, but it wouldn’t prevent a go-around if my flying resulted in an unstabilized approach. My hand tightened around the thrust levers, ready to shove the JT8s to go-around thrust.

Matt peered over the glareshield in search of the runway environment. His head nodded as he periodically cross-checked the altimeter. My lips pursed — a silent plea willing my harried instrument scan to endure a bit longer.

“Approaching minimums,” Matt called. I bumped the thrust levers forward. “Checks.”

Matt leaned closer to the windscreen, as if a few extra inches would matter. Streaks of gray raced over the windows, the runway still behind the veil of reduced visibility. Perhaps it was fitting. Attempting to conquer steam gauges with our glass experience was admirable; assuming the DC-9 would tolerate this challenge was foolhardy. Flying the proven aircraft to minimums was our punishment — a careful-what-you-wish-for admonishment cloaked in the ghostly beeps of NDB identifiers yet to go off the air.

There were two possibilities when the altimeter’s needle reached decision height: see the runway or go around. My eyes lingered on the instrument a second too long. When I shifted my scan to the left, the localizer was creeping off center.

Matt’s voice was the reprieve. “Runway in sight,” he announced. “Twelve o’clock.”

I looked up and saw the pavement unfolding across Wilmington’s green fields. We were slightly off centerline, and I corrected visually. Approach lights flashed beneath us as we descended toward the runway’s threshold.

“Landing,” I replied.

The master warning and caution buttons were in my peripheral vision as I concentrated on the touchdown zone markings. If their blankness indicated surprise, there was still opportunity to witness failure. Of the nearly 1,000 DC-9s built, the number of landings fleet wide was incalculable. My touchdown wouldn’t scratch this tally, but I could still dent some aluminum.

Pavement began unrolling beneath the DC-9 at 50 feet. We passed over the runway’s numbers, the white centerline markings splayed before the aircraft’s lifted nose. At 30 feet, I applied back pressure and eased the thrust levers toward idle.

The main gear should have touched as the thrust levers bumped their stops. Unfortunately, as the engines idled, the DC-9 still streaked above the runway. I nursed the yoke, willing the mains to kiss the rubber stains beneath them. There was a thud as we touched down — not a jarring impact, but the DC-9 made it known it was on the ground. Its speed-brake handle screeched backward as the nose gear thumped against the centerline. We deployed the thrust reversers, although most of our momentum seemed to be absorbed in our firm landing. We stopped about 6,000 feet down the runway.

With the parking brake set, I slid backward and exhaled. My shoulder harness whipped free. The DC-9’s instruments were motionless, a steam gauge laboratory finally at rest. I actually felt like a wild-eyed scientist as the creator of this experiment, with my glass cockpit background as the control. My eyes were also tired from reincarnating my dormant analog scan.

The old instructor was right: It’s more difficult to transition from glass to steam than vice versa. Rather than sending an email via a telegraph, I likened our DC-9 experience to an old rotary telephone. We remembered how to dial, but its circular wheel had to be conjured from the depths where obsolete things are stored in our minds. The DC-9 had a dial tone; it was simply hard to hear over the spinning gyros powering its steam instruments.

A week later, I was preflighting the 737, tapping the FMC’s keypad reassuringly. Our route displayed on the inboard display unit, indicating the exact time between waypoints. As I silently typed, I heard the thundering roar of turbojet engines. I looked up and saw a DC-9 climbing away, dark exhaust spewing from its JT8s.

I reflexively waved. It was a greeting to an aircraft I had the pleasure of meeting. It was also a heartfelt acknowledgement of its timeless success. I smiled as the DC-9 disappeared from view, its pilots connecting the aircraft’s dynamic past to the present.

We welcome your comments on flyingmag.com. In order to maintain a respectful environment, we ask that all comments be on-topic, respectful and spam-free. All comments made here are public and may be republished by Flying.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox