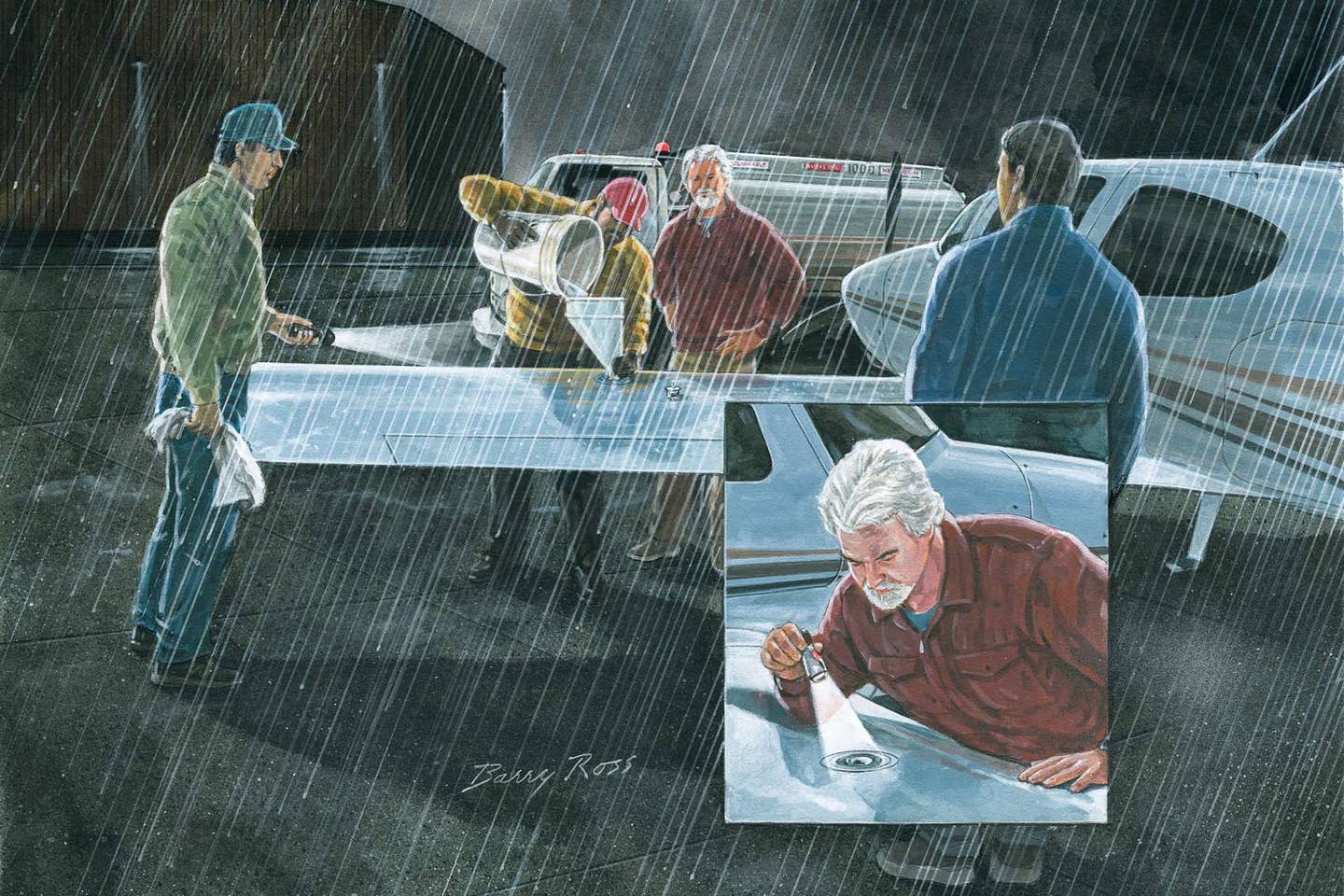

“Upon landing, taxi and shutdown, and before egress, my passenger noticed something wrong on the right wing. ‘Why don’t we have a fuel cap?’ he asked.” Barry Ross

I have never parked my airplane after a more or less uneventful flight and been so dismayed at the sight of my wing when I shut down the engine. The flight, approach and landing were textbook, with no hint at all of the excitement that could have greeted me that night. No, the ailerons were fine, the flaps were retracted completely, the strobes intact and the leading edge had very few bugs. Here is my story.

The Denver air at 7:30 a.m. in February was crisp with single-digit temperatures and not a breath of wind. My buddy and I had departed with a goal of reaching the balmy weather of Orlando, Florida, in a single day. The plan was for a three-leg cross-country flight in a low-wing four-seater.

With 28 to 33 knots of tailwind, we were able to reach the mid-Panhandle of Florida on the second leg, with just a few slight diversions for weather. There was about an hour’s worth of fuel left in the tanks when we landed at 9:45 p.m., and of course the FBO had closed for the night in the sleepy town we chose to visit.

Parked to the side of the small terminal were three fuel tanker trucks. One carried 100LL and the other two jet-A. We couldn’t see a self-service island for fuel, so we found the preverbal phone number to call after hours on the FBO door—and to our surprise, someone answered. I asked, “Is there a self-service pump on the field?” An unexpected “No” was the reply, but an additional unexpected offer followed. “I’d be glad to come out if you need fuel tonight,” the person said.

The night fueler came out to top off the tanks but forgot the fuel truck’s keys and had to go back home to get them. With enough time for us to order a pizza to be delivered from the local chain restaurant, the keys were retrieved, and the truck’s engine sputtered to life.

After pumping 26 gallons into the right wing, the fuel truck’s engine suddenly died. Repeated attempts to restart the old beast were unsuccessful, so the fueler called in reinforcements to try all their secret tricks to nudge old Betty enough to continue fueling my thirsty bird. With no luck after 20 minutes of trying, we were getting tired and frustrated. But we knew the ramp team was too, and they were very apologetic.

The team offered to get a clean five-gallon bucket and drain fuel from the truck’s sump. They found a very big funnel to at least get “some” fuel in my left-wing tank. We planned on waiting for them to drain five buckets of fuel to get us on our way.

With the first bucket full of fuel, they began pouring it into the funnel for the wing tank. Seemingly without warning, the sky opened up and started pouring down rain. We decided that the additional 26 gallons in the right wing and five gallons in the left would get us to our destination with more than 45 minutes of reserve. The fuel team finished emptying the bucket and looked like a NASCAR pit crew when they quickly removed the funnel and replaced the fuel cap to keep the rain from entering the tank.

Read More: I Learned About Flying From That

We jumped into the airplane, started it up, checked the onboard tanks and did the math. “No problem!” Even the rain had stopped—which, from what I hear, is common in Florida.

The run-up was smooth, the needles in the green—and off we went. We kept the fuel drawing from the right tank long enough to balance the wings again and made it safely to our destination. Looking back, that could have easily resulted in a different outcome.

Upon landing, taxi and shutdown, and before egress, my passenger noticed something wrong on the right wing. “Why don’t we have a fuel cap?” he asked. After my heart jumped into my throat, I hopped out and ran over with my flashlight. I could not see fuel in the tank. The wind flow probably sucked all of it out of the wing.

I called the FBO and informed them of the issue, and they promised to check the ramp the next morning, which they did and found no cap. During all the distraction of the fuel truck stopping, changing the fueling procedures and the rainstorm, the fueler probably didn’t put the cap back on—or at least didn’t put the cap-locking lever down—and I failed to do a proper preflight.

Here is what “I learned about flying from that”:

- Good thing the landing checklist says to change to fullest tank before landing.

- I can't fault the fueler for not replacing the cap because I don't know if that actually happened. Had I done a walk-around in the pouring rain, I would have noticed the missing cap.

- Preflight checklists are very important—even outside in the rain, snow, heat and so on.

- Fuel caps for this airplane cost $350.

- When the routine is interrupted, there is a higher chance of distraction.

- Most FBO parts departments don't stock fuel caps.

- Even if the FBO finds the correct part number for the correct airplane, the manufacturer could still send the wrong cap overnight.

- You meet the most-interesting and friendly people when the "you know what" hits the fan.

- When your instructor isn't there, you sometimes cut corners when you're in a hurry or don't want to get your hair messed up. Slow down.

- Sometimes a pop-up rain shower will just walk on by if you relax and give it a few.

A few days later, before putting in fuel for departure, I made sure to drain the fuel sumps twice to look for water, just like I had been taught from my first flying lesson. There actually was fuel in both tanks but no water, so I topped off the tanks and took off, keeping a close eye on the engine sounds, gauges and the engine-out emergency checklist.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox