Should Your First Airplane Be a Taildragger?

A pilot who recently acquired one weighs the limitations and benefits of owning a tailwheel airplane.

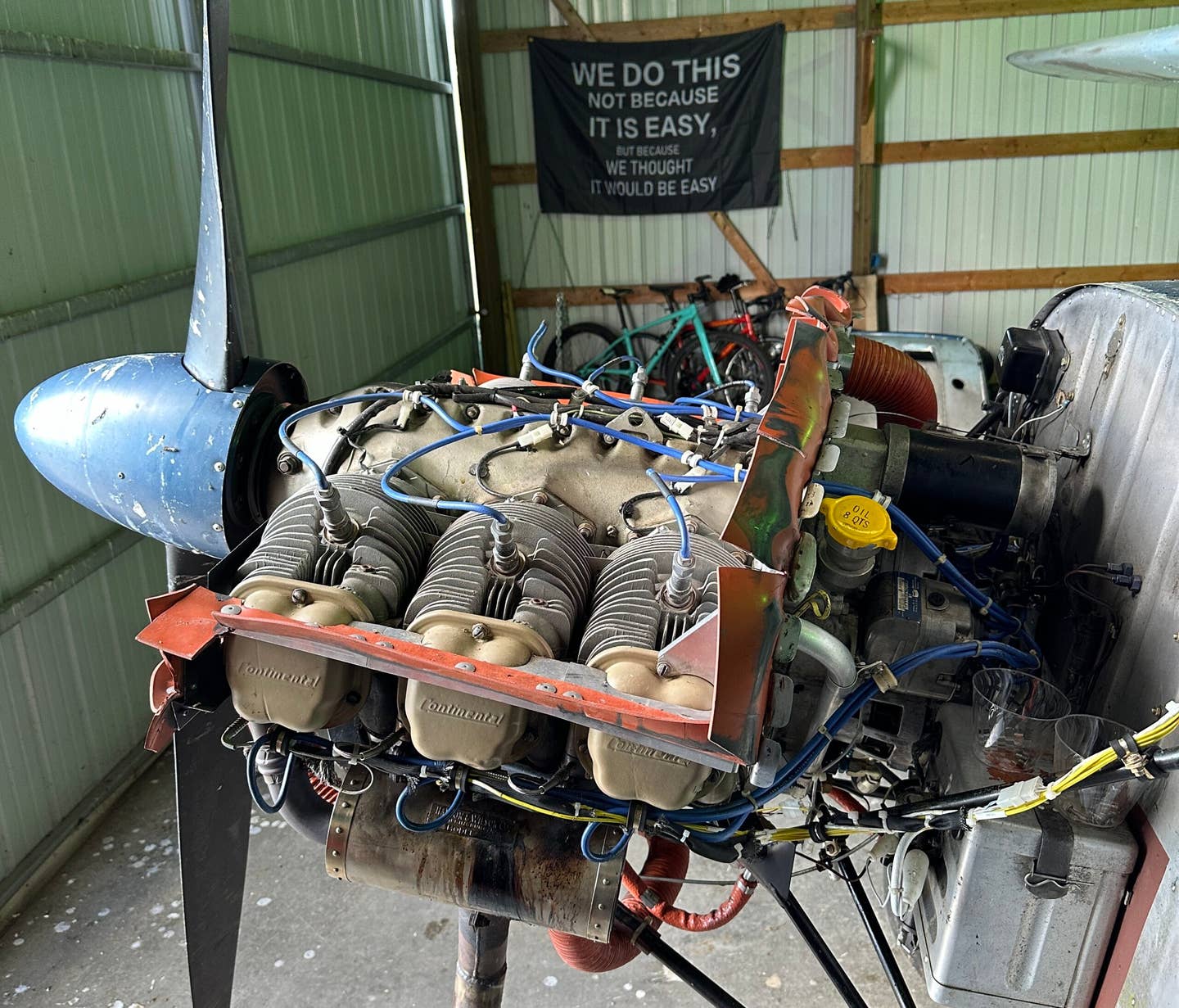

For all the limitations inherent in a taildragger, are the benefits worth it? The answer may lie in factors that are difficult to quantify. [Photo: Jason McDowell]

One point four knots: That’s how much wind it takes to completely alter your weekend plans. That is, when you’re a new taildragger pilot with strictly-observed crosswind limitations, anyway.

Let me explain. Last weekend, there were two small fly-ins taking place within about 50 miles of my home airport. The plan had originally been to attend one or both of them. Both were scheduled for Sunday, and the weather was looking like it just might cooperate.

Here, in Wisconsin, fly-ins have achieved some notoriety for being more than just a simple gathering of airplanes. The homebuilding and restoration communities are vibrant. Warbirds and vintage aircraft are commonplace, and the owners of such aircraft love to gather. Additionally, these events usually feature some pretty tasty cook-out cuisine, typically in the form of bratwurst, burgers, and freshly fried fish.

For all of these reasons, I had been looking forward to a full day of flying around the countryside, admiring beautiful airplanes, and meeting the people who fly and maintain them. But as the day approached, the main meteorological concern shifted from low ceilings to winds that, while not very high, were outside of my personal limitations—by 1.4 knots. In the interest of discipline and safety, I scrapped my plans and dedicated the day to tasks that were far less enjoyable but far more productive.

Cancellations like this were becoming a pattern, but while frustrating at times, they were entirely a product of my own decisions. It was my decision to rent a hangar at an airport with a runway that’s perpendicular to the prevailing winds. It was my decision to be conservative with regard to my crosswind limitations. And, indeed, it was my decision to purchase a taildragger at all.

Posing the Question

The latter decision became a point of discussion with a friend recently. Already a helicopter pilot, he was beginning to explore the possibility of purchasing something with fixed wings and then earning that rating. As fun as helicopters are, their insanely high hourly rental rates put a damper on things.

It was he who posed the question of whether the benefits of owning a tailwheel airplane might be outweighed by the downsides. I had, after all, been canceling flights fairly regularly owing to my conservative crosswind limitation. Through his lens as a prospective owner and mine as a new one, we explored the question.

A taildragger’s downsides are few in number but pretty consequential in nature. The primary downside is, of course, the lack of stability on the ground as compared with a tricycle-gear airplane.

In a tricycle-gear aircraft, the airplane naturally wants to align itself with the runway when touching down on the main gear. Imagine trying to push a car door open at highway speeds. It wants to remain closed, and the further you push it, the more strongly it tries to return to a closed position. Simply letting go will restore equilibrium.

Conversely, it’s possible to salvage a tailwheel landing in which you touch down in an extremely slight crab…on grass, anyway…but the further out of coordination you are, the more difficult it will be to recover. From the perspective of stability, a tailwheel airplane’s lack of stability would be comparable to performing the same car door experiment in a car with so-called “suicide doors,” hinged at the back.

Crack the door open just a bit, and it will pull outward slightly. Push it open another few inches, and it will take most of your arm strength to hold in position. Each subsequent inch will increase the outward force exponentially until you can no longer hold on. The farther away from neutral you go, the more difficult it becomes to recover. Just like landing a taildragger in a crab.

The Other Downside

The other major (and related) downside to a tailwheel airplane is the higher cost of insurance. I commonly hear new taildragger pilots being quoted around $2,000 per year for insurance on types like the Cessna 170, and less than half that amount for the tricycle-gear 172. This amounts to an approximate $100/month premium for the privilege of flying a taildragger.

Considering these factors, then, what benefits are in play? And looking back, are they worth it? And in my case, has it been worth having to cancel many flights because of crosswinds that would have been manageable in something with a nosewheel?

The Technical Advantages

The actual technical advantages to owning a tailwheel airplane are legitimate, but few apply to my situation as a mediocre private pilot playing around at grass strips in the upper Midwest. The configuration provides more propeller clearance and eliminates the possibility of a gopher hole swallowing a nosewheel and ruining your engine. It also eliminates the possibility of a bad landing damaging the firewall of the airplane. Taildraggers are typically beefier and excluding ground loops, are more resistant to damage from rough surfaces and botched landings.

Immensely Satisfying

There’s another advantage. One that’s entirely legitimate but nearly impossible to quantify or measure. Because a taildragger demands more involvement from the pilot—more physical and cognitive skill to achieve consistently good landings in varying conditions—they can be immensely satisfying to fly.

The comparison is not unlike that of a car and a motorcycle. Most modern cars are admirably easy to maneuver through sweeping curves at speed. One simply turns the wheel a bit to remain in their lane, and the car’s tires, suspension, and sometimes stability control ensure the driver is left alone to continue composing their text message. Negotiating that curve is easy and efficient.

The motorcycle, on the other hand, is the tailwheel of road vehicles, far more demanding of the operator and far less forgiving of miscalculations. The motorcycle rider must continually remind themselves to focus farther away as they consider their line through the curve, modifying it as necessary. Along the way, body English is required; some pressure on the outside peg here, a flex of the torso there. The experience is a precisely calibrated and controlled rush, human and machine depending on each other to negotiate whatever challenges lie ahead.

It’s a big price to pay for simply getting through a curve in the road. But to those of us who bask in the ongoing mastery of a machine, it’s hugely satisfying…and addictive. To step back into a tricycle-gear airplane is to dismount the motorcycle and slide back behind the wheel of the car— fun in its own way, but a wholly different experience.

It was this difficult-to-quantify quality of taildragger flying that I attempted to convey to my friend. Yes, an airplane with tricycle gear is more logical in most ways. It’s cheaper to own, more forgiving to fly, and quicker to master. It enables you to operate in far more challenging winds. But a taildragger will never leave you feeling unchallenged or bored…and when you hop out and walk away after successfully negotiating a challenging crosswind or a particularly lumpy airstrip, you feel that much more personal satisfaction.

So despite having to regularly cancel planned flights because of my conservative personal crosswind limitations, I think it’s fair to say that I’m happy with my airplane choice. Sure, the learning curve is long and steep, but on the other side are many years exploring all the lush grass strips that pepper the rolling farmlands of Wisconsin and Michigan. And as far as I’m concerned, I’m going to wring every last bit of enjoyment out of the experience.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox