Finally, It’s Time To Solo

As this pilot gets ready to go in the air alone for the first time in 19 years, lots of thoughts come and go.

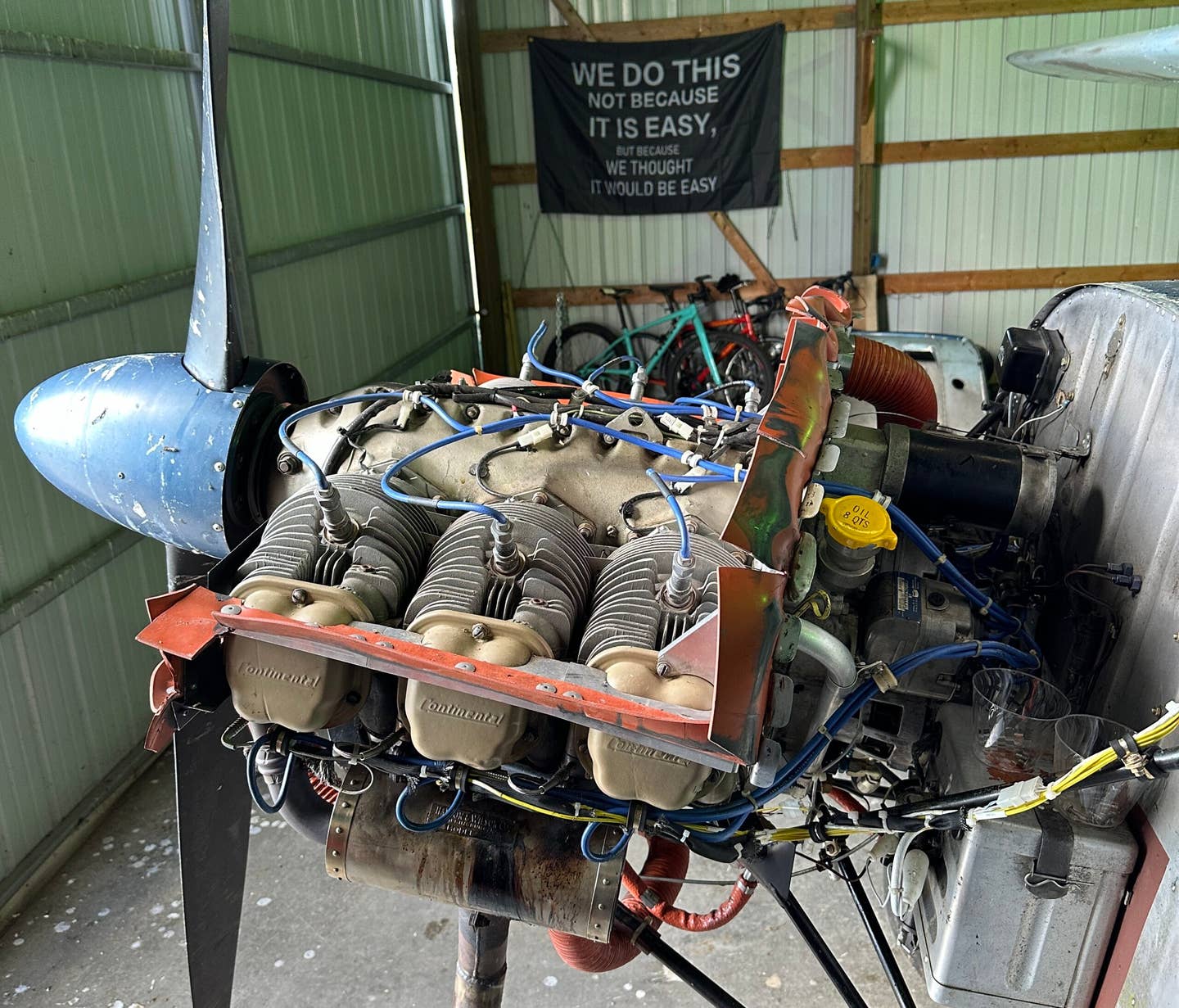

At long last, weather conditions, airworthiness, and proficiency converge to enable a first solo in the owner’s first airplane. [Photo: Chris Litzkow]

In a classic article from the magazine’s archives, FLYING’s Tom Benenson took a look at pilot proficiency. He questioned which theoretical pilot is safer, a 10,000-hour pilot who has flown only 20 hours in the last year or a 200-hour pilot who has flown frequently in the last month. He provided insights regarding the FAA’s minimum proficiency requirements, and questioned whether it’s prudent to apply these minimums in practice.

At no point did Tom question the proficiency of someone who hasn’t soloed an airplane in 19 years. Mostly because it’s a stupid question, and also because anything resembling proficiency would have departed the brain sometime during the Bush administration. But also because those of us so to whom this question applies know damn well how rusty we are.

On the day I was planning to solo my Cessna 170 for the very first time, these thoughts began to swirl around my head from the moment I woke up. I had spent the preceding weeks flying with my instructor in preparation for this. Flight after flight, he threw a barrage of challenges my way, and I managed to handle most of them without looking as out-of-practice as I felt.

Accordingly, he signed me off to solo my airplane. Subject to crosswind components of 8 knots or less, visibility of greater than 3 miles, and ceilings of at least 2,000 feet agl, I was free to go play. He also signed me off to fly to several other airports, one of which happened to be the airport at which I was scheduled to drop my airplane off for its first annual inspection.

The pressure, therefore, was on. It was time to leave the nest of supervised comfort and see if I still possessed the ability to safely fly solo. And it was time to start thinking about solo cross country flights so that I may get the airplane to the mechanic 50 miles away without having to rely on friends to do so. Generous as they were with their time and expertise, I had long been feeling like a burden to them, and I was eager to become self-sufficient.

On the morning of my planned “first” solo, the nerves were fully spooled up, and I was simultaneously dreading and looking forward to the flight later that afternoon. The forecast looked promising, with airports in the region all showing clear skies and light winds. I closely monitored them through my workday before finally heading down to the airport that afternoon.

Upon arrival, the windsock informed me that the local conditions were perhaps not quite as idyllic as the METARs at surrounding airports. While the sky was indeed clear, the winds had picked up and had shifted to a crosswind. I preflighted the airplane anyway, and when I walked back outside to check the windsock a second time, the taut fabric extended outward like a giant orange middle finger to my plans.

The crosswind wasn’t a strong one, but it was enough of one that I opted to delay my flight. Though I’d been doing fine with stronger crosswinds during my training, I didn’t want to have to deal with any on my first solo flight in the airplane. I took the opportunity to dig through old boxes, reorganize things in the hangar, and tidy up.

After about an hour or two, I walked outside to have another look at the windsock. The wind had died down…and mercifully, it had also aligned with the runway. I monitored it for a little while longer, and finally made the call; waiting had become tedious, conditions were good, and so, it was time to fly.

Despite having thoroughly preflighted the airplane in the hangar, I pulled it out and preflighted it again. The winds had calmed down enough that the paramotor operator on the field had just begun operations. Seeing a couple of the instructors zipping out to the runway aboard a minibike, I flagged them down and described my plan to conduct three takeoffs and landings.

Ever the professionals, the instructors happily agreed to pause their operations for me, and encouraged me to take my time. They said they’d simply hang out along the sides of the runway and take a break while I flew. Every time I’d interacted with this group, they’d impressed me with their level of discipline and cooperation.

As I walked back to my airplane, I wondered whether I should have mentioned that this would not only be my first solo flight in a taildragger, but that it would also be my first solo flight in any airplane since 2003. I opted not to say anything about my grotesque lack of proficiency. I was confident I could keep the airplane on the runway, and figured such a warning would create unwarranted fear among the daredevil paramotor crew.

You can’t help but feel cool when taxiing your very own taildragger. And while looking cool has never been a major goal of mine, I did my best to provide a steely-eyed look of confidence as I taxied past my audience lining the touch down zone of the runway. They were all smiles and waves, and I returned a laid-back wave to them as I focused on holding full up elevator and carefully searching for woodchuck holes in the runway.

With a tap of the left brake, I performed a jaunty 180 as only taildraggers can do and lined up for takeoff. After readjusting the mixture to full rich and methodically running through the pre-takeoff checks, I applied full power. Without the weight of my instructor next to me, the tail came up earlier than usual, and my solo PIC bravery was rewarded with a relatively quick hop into the air and a healthier-than usual climb rate.

And just like that, I was soloing an airplane again.

From the time I cleared the trees on the departure end of the runway, the nerves melted away, never to return. The airplane performed perfectly, and it was no great effort to hit my target altitudes throughout the pattern. The air was smooth and the sinking sun cast golden light from behind as I turned final.

Other than silently reminding myself to avoid killing the nice people sitting alongside the runway, I didn’t do anything different than usual to set up for landing. Flaps 40. Control forces nicely trimmed away. And just a touch of power to maintain 65 mph on the way in.

My adherence to routine paid off, and I was able to smoothly settle into nice, three-point, full-stall landings. Fun as wheel landings had been to perform with my instructor, I opted not to push my luck by introducing any more complexity or difficulty than absolutely necessary. After my third landing, I radioed a thank you to the nice paramotor folks and headed back to the hangar.

With this milestone checked off of my to-do list, I reflected that proficiency can be a funny thing. While a pilot who isolates themselves from aviation entirely can expect to encounter a significantly steep learning curve upon their return to the cockpit, regular ride-alongs can do wonders for one’s comfort level when flying resumes. Though I hadn’t soloed in many years, my regular flights with airplane owners as part of the Approachable Aircraft series kept my head in the game to a certain extent, and this eased the process of returning to proficiency.

For many of us who are forced to focus on life at the expense of flying regularly, this may be the answer to a safe return to the air. By cultivating relationships with other local pilots and joining them for an occasional $100 hamburger, we can reimmerse ourselves into the flying environment with a minimum investment in time or money. While no substitute for formal instruction, this has the effect of shaking the dust off of the general aviation neurons in our brain and setting us up for success when we finally are able to continue our own flying.

For me, the biggest challenge was getting over that first solo flight and conquering the doubt that I’d still be able to fly safely on my own. As it turned out, that doubt lived only in my head, and was extinguished by my first takeoff. A mental switch was flipped, and as I buttoned up the hangar later that evening, I found myself looking forward to the next flight.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox