Sleuthing To Find the Right Airplane

Jason McDowell outlines the arduous process he went through to find the aircraft that was just right for him.

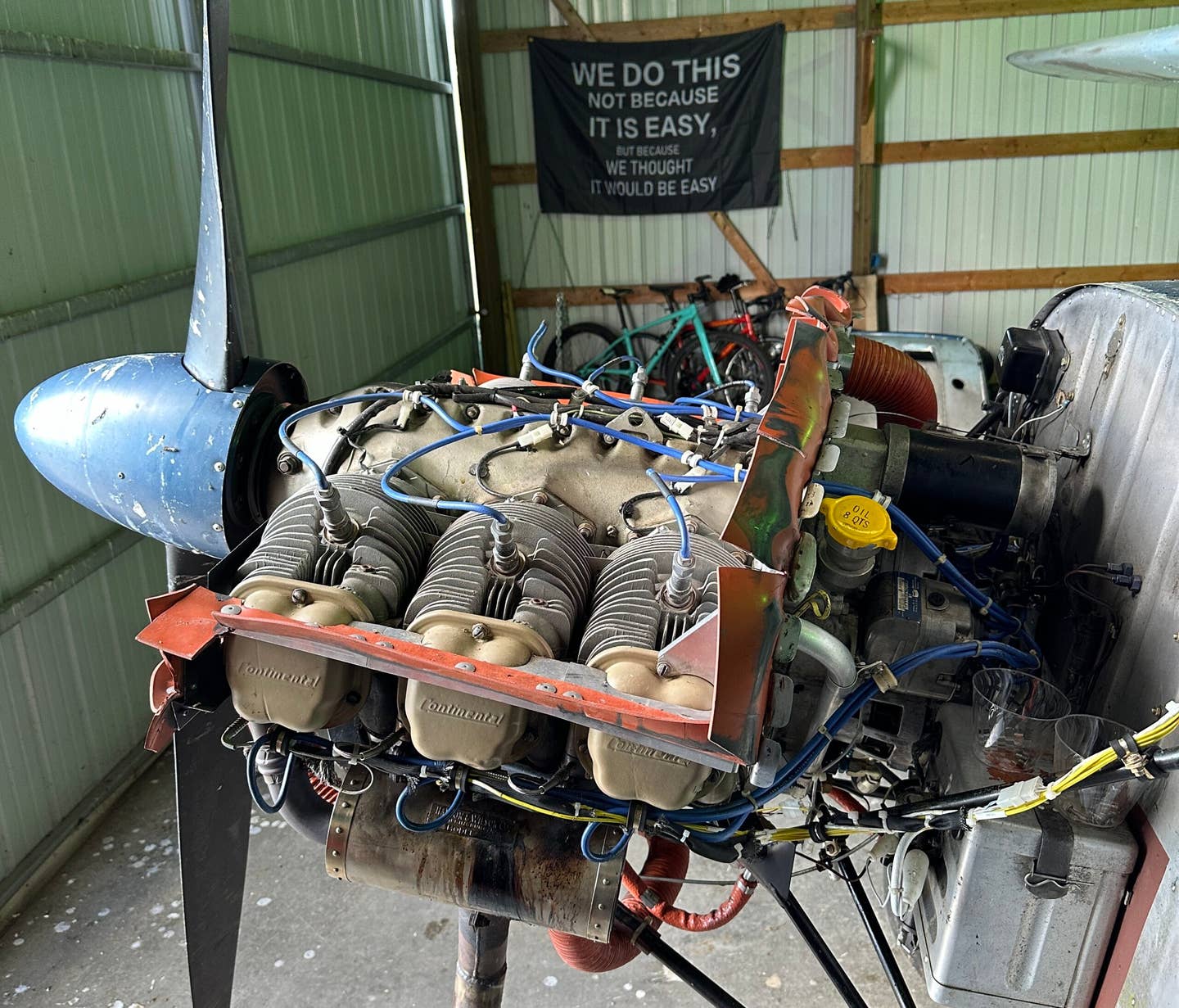

Some of the best airplanes are tucked away in hangars and unlisted; finding them requires some investigation. Chelsea Frost

To become a pilot, one must also become a bit of a scientist, building an understanding of aerodynamics and meteorology. A pilot must also become a bit of an engineer, embracing the systems of their aircraft and learning how to detect and address signs of trouble.

But to become an owner, one must first become a detective. In the current market, airplanes are routinely sold within minutes of being listed, and unless you happen to call immediately and secure the first spot in line, you have to get creative with your search techniques.

Know What You Like

My own search began with defining my mission and seeking out some types to fly. I knew I’d mostly want to explore the huge number of lush grass strips that pepper the Great Lakes region. Of particular interest are the dozen or so island airports surrounding the state of Michigan.

I also knew I Iiked the idea of a taildragger; without a relatively fragile nosewheel, the rugged landing gear would be a good match to some of the rougher strips. The configuration also serves as an antidote to boredom while demanding continuous vigilance and skill building from the pilot.

Like a motorcycle, a taildragger lavishly rewards good technique with a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment—and this isn’t something that fades with time or experience. If anything, it fuels the addiction and leaves you wanting for more.

Learn, Learn, Learn

After settling on a Cessna 120/140 or its bigger brother, the 170, I entered step two of the investigative process—learning as much as possible about those models in their respective owner’s groups. Which subtypes and years to avoid, which to seek out, and what problem areas to focus on. Before long, I’d created a list of minimum requirements, and disqualifiers, for each model.

A metalized wing on an early 140, for example, was a disqualifier. The early 140s had fabric-covered wings that fly beautifully, but when that fabric is replaced with metal as part of an STC, it robs the airplane of 50 to 75 pounds of precious useful load and also of the wonderfully light, precise feel of the ailerons.

The 170s tend to be significantly more expensive, and with a modest budget, I couldn’t afford to be so choosy. The 170B with its massive flaps was the ultimate, but those tend to be priced accordingly. So while I also created a list of requirements and disqualifiers for 170s, these were far less rigid than those I created for the more affordable 120s and 140s.

Begin The Search

With the initial research and preparation complete, I was ready to put on my detective hat and begin the actual search, seeking out an airplane that met my requirements and budget. Before long, I had assembled an arsenal of bookmarks in my browser. With a single click, each would take me directly to the latest 120s, 140s, and 170s listed on the half-dozen or so most popular aircraft classified websites.

My search also encompassed some less common techniques. Every week or so, I’d use a crawler called SearchTempest to scour every Craigslist listing in the nation. With just a few clicks, it would present me with every mention of, for example, “140A” in every state. This would occasionally reveal an airplane in some rural corner of North Dakota or Oklahoma that didn’t appear anywhere else on the web.

It became a daily workflow; immediately after brewing my morning coffee, I’d sit down at my computer and canvass each site. It didn’t take long to scan through the offerings. At a glance, I’d easily identify and disregard the airplanes I’d already seen. Here’s the cool brown and yellow 120 in Ohio with the 50-year-old wing fabric. There’s the nice green 140 in Nevada with the less desirable 85 hp engine.

When I’d spot an unidentified newcomer, I’d descend upon it like a ravenous hawk attacking its prey. A quick glimpse at the specifications would indicate whether it was worthy of further investigation. I’d go down the list. Model year, engine type, fabric condition, price, panel. I’d take each element into consideration. More often than not, I’d instantly identify a disqualifying characteristic and disregard that airplane in any subsequent searches.

Zeroing In

A handful of times, I came close to making a purchase. A 1948 Cessna 140A in nearby Minnesota looked perfect. It was equipped with my ideal engine, the Continental C90, that only had about 100 hours since the last major overhaul. The panel was clean and in good shape. And it was priced right. But a conversation with the seller revealed a lot. I learned the overhaul was about 30 years old and although the airplane had been kept in a climate-controlled hangar, it had been periodically started and run on the ground.

This, I came to learn, is worse than never running the engine at all. A quick ground run won’t bring the temperature high enough to evaporate the internal moisture, and the subsequent condensation tends to lead to internal corrosion. I began to arrange for a local mechanic to perform a pre-purchase inspection, and he recommended removing one or two cylinders to have a look at the condition of the crankshaft and camshaft. The seller politely declined this plan, preferring not to remove any cylinders. I understood, we parted on good terms, and my search continued.

I later found another 140 listed for sale on Facebook Marketplace in North Carolina. It checked nearly every box—it had my desired engine, it had been flown regularly, and it had some nice avionics and accessories. It was the very best-scoring airplane on my comparison matrix. Unfortunately, I just couldn’t get over the color, and my hesitation proved fatal to the impending purchase when another buyer beat me to it.

This process would continue for months. I’d spot an airplane with good potential, I’d investigate further, and the investigation would come to an end upon learning about some disqualifying characteristic. One one hand, it was frustrating, and I felt as though I was making no progress. But on the other hand, it was an educational process, and I continued to stash money away into my airplane fund and my ensuing budget gradually grew.

Eventually, I began to ignore the usual sources to find aircraft for sale, and instead started to seek out examples that weren’t being actively listed anywhere. If I spotted something that looked like it had potential, I’d look up the tail number on the FAA’s site and find the name of the owner. If a quick Google search revealed their phone number or email address, I’d reach out directly to ask whether they would consider selling their airplane.

At Last, The One

After all these efforts, it was good old fashioned word of mouth that brought me to the airplane I would ultimately end up purchasing. While chatting with a friend, I mentioned in passing how difficult it can be to find the perfect airplane. When I elaborated and described my dream Cessna 170B, she said she vaguely remembered a friend talking about his hangar neighbor with one.

It took multiple steps and multiple introductions to get in touch with the owner, but the effort proved to be worthwhile. It was indeed a coveted 170B, adorned in original, well-worn 1953 paint and a fairly ratty interior. These characteristics helped to bring the value down to a level I was able to manage.

The owner was a retired rocket engineer. His work is, at this very moment, aboard the Voyager 1 space probe, 14 billion miles from planet Earth. I concluded he was most likely able to properly maintain a Cessna, and I was happy to learn he had owned it for over 40 years.

Over the subsequent few months, we spent hours chatting on the phone about the airplane, and thankfully, I was finally able to extricate myself from the exhausting process of aircraft shopping. The ensuing chapter of actually making the purchase and getting it home would be exhausting in its own right, but I was thrilled to be taking the next step in the process.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox