Lawmakers Warned of International Space Station Transition Gap

Private companies fear losing to China in a move toward a commercial space economy.

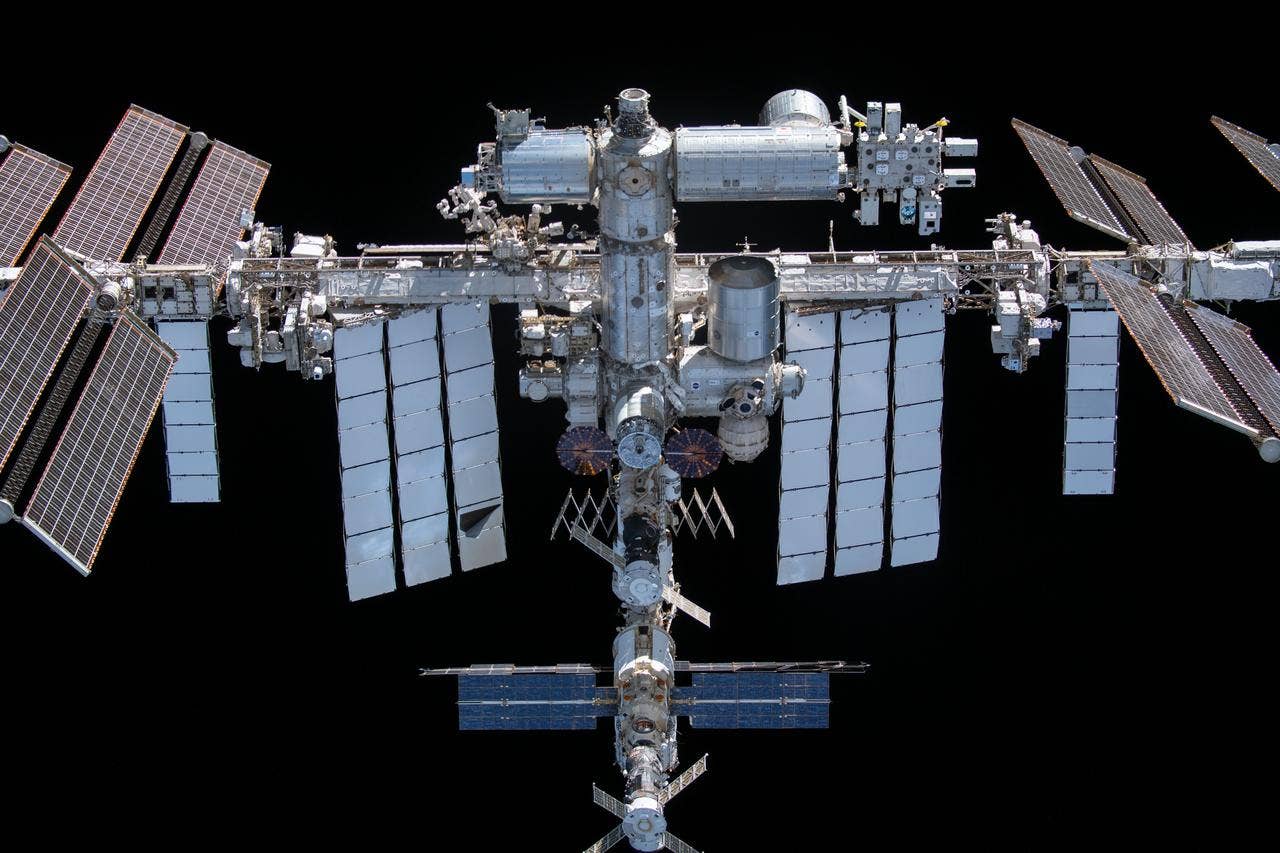

The International Space Station is expected to be in use through 2030, after which it will be deorbited. [Courtesy: NASA/Thomas Pesquet]

The U.S. is at risk of losing its leadership role to China in low-Earth orbit (LEO) space activities if it fails to manage the transition to a commercial space economy, according to space station developers.

At a U.S. House Science, Space, and Technology subcommittee hearing on Wednesday in Washington, D.C., lawmakers were warned about there being no clear path toward ensuring that NASA’s aging International Space Station (ISS) can be deorbited after 2030—its designated end-of-life year.

That’s due in part to a lack of funding, including those needed to purchase a spacecraft known as the U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) that will perform the final deorbit maneuver of the ISS.

“We are standing at the precipice of achieving one of the most audacious goals humanity has dared to reach for since we built the International Space Station—fulfilling the vision of humans living and working in space in an ecosystem of economic expansion, marking the best of American industry and innovation,” Mary Lynne Dittmar, chief government and external relations officer for commercial space station developer Axiom Space, said during her subcommittee testimony.

However, Dittmar said, without clear direction and funding from Congress, the continuity of Americas’ LEO presence is in danger.

“The likelihood of a gap in LEO following the decommissioning of the ISS has never been greater,” Dittmar said. “The consequences of such a gap cannot be overstated. It will result in ceding our role and position as a leader to China, a role that—once lost—we may never get back.”

Dylan Taylor, chairman and CEO of Voyager Space, a competing developer, pointed out that a funding increase authorized by Congress will “bolster investor confidence and accelerate early investment” by private companies.

“Early investment helps address design challenges sooner, fosters a customer base, and avoids costly late development changes,” Taylor said. “Lack of investment in 2024 and 2025 would jeopardize schedules for all providers and increase the risk of a gap in U.S. human presences [in LEO].”

Deorbiting ISS

Responsibility for the controlled deorbiting of the ISS back to Earth—ensuring that it avoids populated areas—is shared among the five space agencies that have operated the station since 1998: NASA, Canadian Space Agency, European Space Agency, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and Russia’s Roscosmos.

The Joe Biden administration has included requests for both the deorbit vehicle and recovery efforts coordinated by a ground station located on Guam in an emergency supplemental appropriations request.

“NASA continues to believe that funding for both of these is a pressing requirement,” said Ken Bowersox, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations.

Bowersox said his agency will continue scientific research and technology work in LEO by transitioning to services provided by one or more commercial space stations.

“It is NASA’s goal to be one of many customers in a robust commercial marketplace,” Bowersox said. “In order to maintain an uninterrupted human presence in LEO, NASA is striving to have at least one operational [commercial space station] in orbit before ISS is ended.”

Customer Outlook

While NASA plans to be an “anchor tenant” once the transition to commercial stations occurs, that won’t be enough to sustain it financially. An approach to developing a commercial market has come through the private astronaut missions over the last several years that have included those from other countries, according to Dittmar.

“As those missions have progressed, they’ve revealed the interest of international entities to participate in human space flight,” said Dittmar, who named Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Sweden as examples. “Other countries are very interested in our commercial platforms, including interest in doing science research, technology development, as well as flying humans into space.”

Said Taylor: “A lot of the biopharma companies would like to do drug development on the ISS, so I see this as a huge opportunity to accelerate their plans. There’s a huge appetite for international space commerce.”

Regulatory Hurdles

But Dittmar and Taylor, along with Republican lawmakers at the subcommittee hearing, expressed concern about another potential obstacle in the transition to a commercial LEO regime—regulations recently proposed by the Biden administration.

The White House unveiled in November a proposed mission authorization system for regulating and overseeing commercial space activities. The 24-page draft document divided oversight between the Department of Transportation and the Department of Commerce.

Such bifurcated authority, Dittmar asserted, would likely serve to slow down commercial space development.

“We feel there is a great deal of room for communication difficulty between the agencies,” she said. “There is an interagency process that is called for by the proposal that would require collaboration and discussion, [so] we’re concerned about the delays that might be imposed by that. Regulatory frameworks need to be streamlined as much as possible.”

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox