“I flew out over the ocean and went through the various maneuvers, enjoying the ride and not really thinking that it would be my last as a PIC.” Joel Kimmel

In fall 1967, I was a Marine second lieutenant and completed my first solo in a Navy T-34. After a couple of times around the pattern, the instructor got out, slapped me on the helmet, and told me to make three touch-and-goes and come back to pick him up.

In fall 2017, I completed my last solo, this time in a flight school’s Cessna 172. Between the two, a lot of gas went out the exhaust as I chased flying jobs.

After that first flight, I went through VT-2 at Whiting Field in Florida, flying the magnificent T-28C/B. Having requested jets, F-4s or A-6s, I found myself in North Carolina at New River Marine Corps Air Station, flying the CH-46 Sea Knight—a helicopter later called the “Phrog,” but in a loving, respectful way.

For me, flying Marine helicopters in Vietnam was the ultimate adventure. The job itself was simple enough: take care of the “grunts” on the ground, regardless of weather or the fact you were regularly being shot at. I loved it. I flew for a year, came home with a bunch of medals and, after a tour in the training command, was unleashed on an unsuspecting civilian world.

I ultimately wanted to fly for the airlines, but airline hiring has more ups and downs than a pork-bellies futures chart. I interviewed with the “spooks” but wanted an accompanied mission of some kind. I talked with Air America but found the same problem: no families included.

A few years later, I was on the Hawaiian island of Maui, still not flying, but I was bartending and having a lot of fun. I realized that I couldn’t do that forever—that I should go flying, which I could do forever. After sending out a batch of résumés to various companies in Hawaii, I was picked up by Aloha Island Air, flying de Havilland Twin Otters around the islands.

After three years with Aloha Island, and a lot of library time searching for operators in Africa, I was hired by Air Serv to fly Twin Otters out of Lokichogio (“Loki”), Kenya. Loki was on the border with Sudan, which was embroiled in its continuous civil war.

In many ways, the job was similar to the one in Vietnam: rough country, taking care of relief workers in a hostile area, but not shot at as much.

Check out our new content: I.L.A.F.F.T. Podcast

After Sudan, I was working for a drilling company in Algeria, working a five-weeks-on, five-weeks-off schedule in the virtual center of the Sahara. Finally, through connections I had made in Loki, I was hired by Champion Airlines to fly the “big iron,” Boeing 727s. Later, I was in 737s and Twin Otters for Saudi Aramco in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. I was there on 9/11—an interesting time.

Returning to the US, I taught ground schools and got my CFI-I. I worked for flight schools in the Los Angeles area and enjoyed the interaction with the students until one porpoised on her first solo landing and tore up the airplane. So much for that job. Fortunately, she wasn’t hurt.

I was hired by a Cessna Caravan company in Hawaii, but things started to change. During training, I couldn’t remember simple procedures or checklist items, things that I had easily mastered in previous years. Consequently, ground school did not go well.

I returned to the mainland and worked for a flight school out of Santa Monica Municipal Airport (KSMO) in California, but the problems continued. I didn’t tie down an aircraft—twice. I wasn’t being lazy; I just forgot. That company moved their operation, and I moved to another flight school. The instruction seemed to be going better, but I often had to go through a long process to remember what I wanted to say to the student.

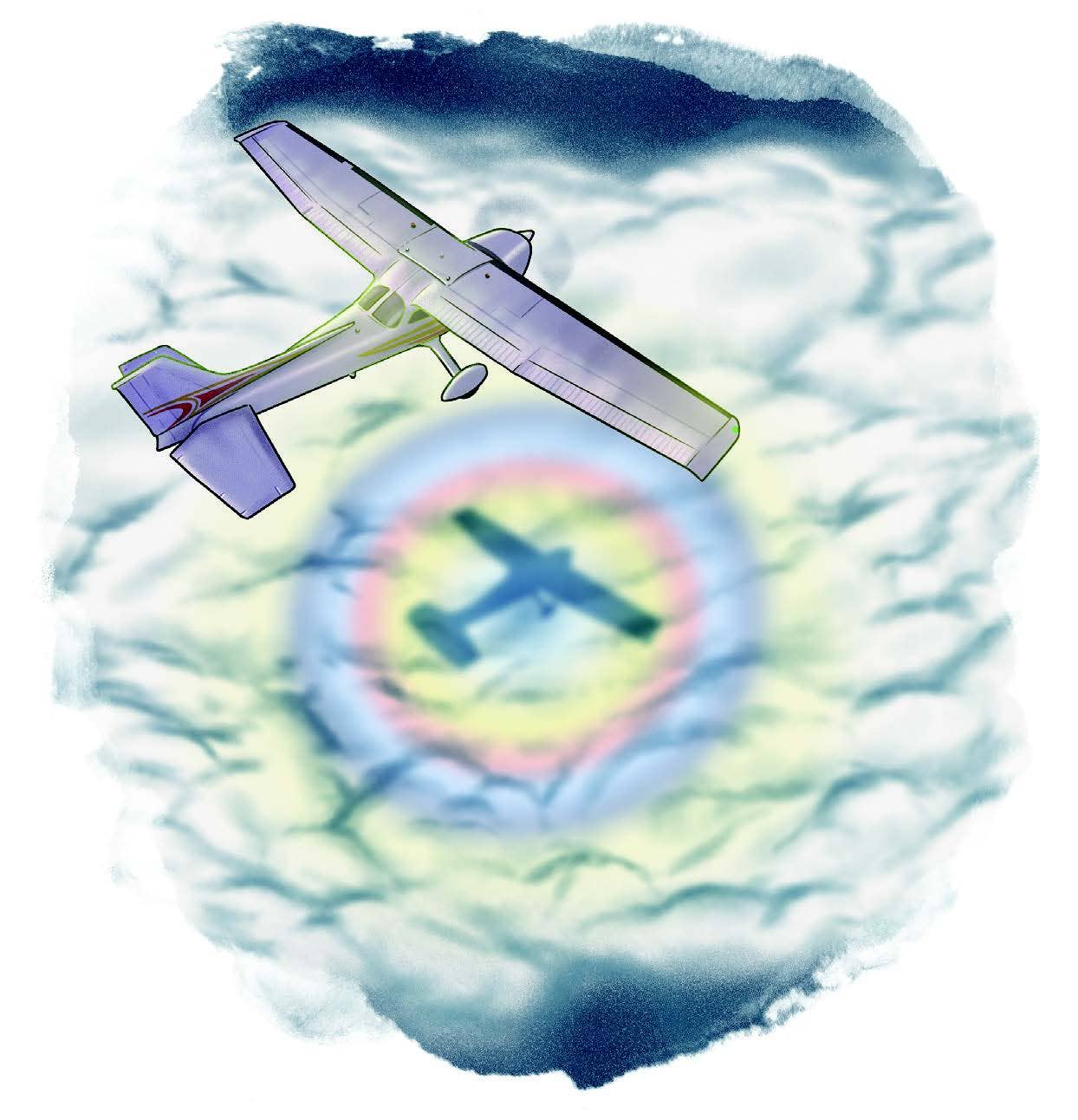

I was taking out a renter for an area-and-aircraft checkout, but I had left my iPad, filled with all the ForeFlight goodies, in the car. I didn’t even think about it, though I had been a dedicated “don’t leave home without it” user. Weather was marginal—low scud with some haze—but I still could see the ground. We went out and did the usual maneuvers and returned to the airport. Taxiing in, ground control called and gave me a number to call. Yeah, the FAA.

A week or so later, a student and I entered the downwind, and she landed normally, no big deal, but I once again received the call-the-feds message. A couple of weeks later, I was invited to visit the local FSDO for the dreaded 709 meeting—a check ride to reevaluate my skills.

In the FSDO office, I met with three examiners. The lead said they had two things to discuss. One, that I had neither acknowledged nor obeyed a tower instruction to “go around,” break off the landing and reenter the pattern. And two, that I had violated the nearby Class Bravo airspace. I had no memory of either incident and said so.

The second man at the meeting took out some papers and showed them to me. One was a radar track of our flight, showing it crossing the departure path from the Bravo airport. The first guy asked, “Didn’t it occur to you that you weren’t where you should be when you saw the airliners taking off under you?”

Read More: I Learned About Flying From That

I told him that we were above an undercast and had only occasional glimpses of the surface, but that everything was clear above and around us. The second guy brought out a cassette recorder, and I heard my voice calling for landing and the tower telling me to go around. I have no memory of either call.

The dates were set for an oral and a flight test. All would be to ATP standards. Great. It had been nearly 20 years since I had obtained my ATP, and I had been busy flying in distant places, far from the FAA, and not reviewing the books as I should have. Besides, remembering procedures, checklists and manuals had never been a problem—until the Caravan ground school.

I went home and studied but could not maintain my concentration or, upon review, remember what I read. I had years of teaching that exact material and couldn’t remember it 20 minutes later. A meeting with the FAA confirmed that maybe I had, as the representative said, “lost a step.”

A week later, we all met at the FSDO again, and I surrendered my certificates: an ATP and airplane-multiengine-land certifications, with B-737 and G-IV type ratings; as well as airplane-single-engine-land, rotorcraft-helicopter and instrument-helicopter certificates, with BV-107 and SK-58 type ratings. I asked for and received a 24-hour temporary certificate and drove back to the airport where I checked out a Cessna 172.

I flew out over the ocean and went through the various maneuvers, enjoying the ride and not really thinking that it would be my last as a PIC. I asked for the ILS under VFR conditions back in. At pattern altitude, I called for an overhead break and landed gently on the numbers, taxied in, and tied down the airplane. As I was walking back to the office, a couple was walking toward me, headed for their airplane. The woman said something to the man, who turned to me and said, “She said that you really look like a pilot.”

“I am a pilot,” I said.

It was a couple of hours later I realized that, after 10,000-plus hours across 50 years in all kinds of flying machines over all parts of the planet, I had lied to her.

This story appeared in the August 2021 issue of Flying Magazine

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox