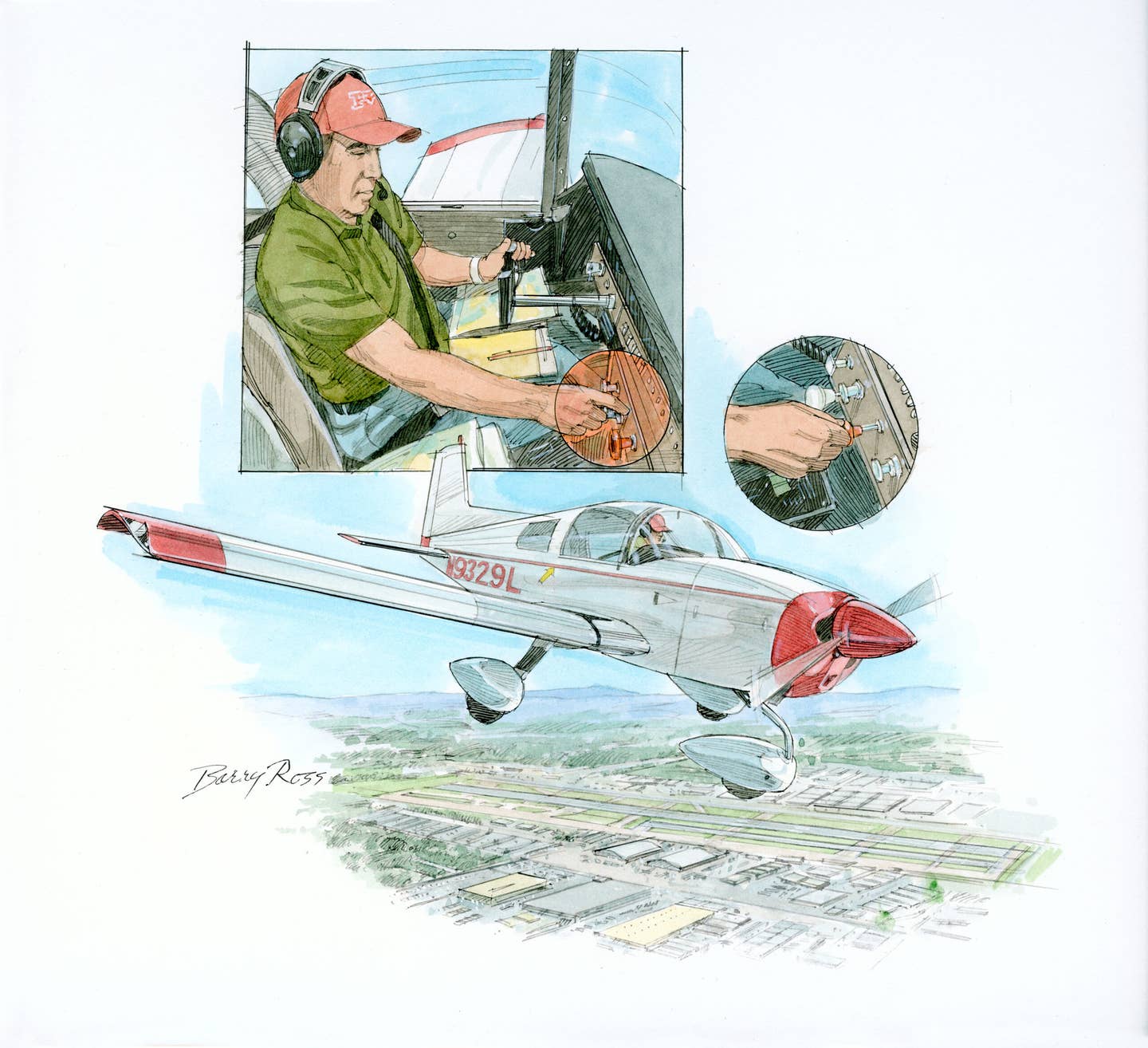

To see more of Barry Ross’ aviation art, go to barryrossart.com Barry Ross

As on all major holidays, July 4, 2015, was a day to take my beloved Grumman Yankee out to stretch her legs and keep my flying skills proficient. Never did I expect that this would be a day of reckoning and facing up to my first inflight mechanical failure in more than 36 years of flying.

When I took that flight, I had not been flying recently. Two frustrating months had gone by post annual when business trips had taken me out of town. I was eager to spend a good couple of hours flying around scenic Southern California.

I took my sweet, leisurely time that beautiful Independence Day. My home base, Santa Monica Airport (SMO), was quiet, not like the usual frenetic day with its mix of all sorts of piston airplanes amid the haute crowd and their business jets. The sight of a Gulfstream swooping onto Runway 21 like a Klingon Bird of Prey always made me stop and admire. Today, while holding to take the active, was no different as the Hilton Hotel’s Gulfstream crossed in front of me, its wheels reaching like talons clawing for the concrete.

The tower’s instruction, “Grumman 29L, Runway 21, line up and wait,” interrupted my thoughts.

Moments later, I was off and climbing through 500 feet, turning left 10 degrees for noise abatement. The Penmar Golf Course, where Harrison Ford had only recently put his Ryan PT-22 down after a catastrophic engine failure, flashed below me as I headed toward the shoreline. I made the right turn I had requested and climbed along the Pacific coast to 4,500 feet. I checked in with SoCal Departure for flight advisories and settled in for the first leg of my holiday renewal to Camarillo Airport (CMA). The Los Angeles basin was glorious.

A flawless landing — you know, the kind where the stabilized approach was right on the money, and you get your reward when the mains “kiss” the ground — had me ebullient.

I taxied back for takeoff from Runway 26. Takeoff clearance came right back, and off we went with smooth rotation as my modified Yankee left the ground, climbing up and over 1,500 feet. I bid CMA a “change of frequency” and contacted Approach for advisories to Van Nuys Airport (VNY).

I settled back and took in the view of the immense Los Angeles basin below. I pinched myself, realizing just how fortunate I was today, flying in my own airplane in this amazing country that was celebrating its 239th birthday.

I began to plan for my entry into VNY. The airport was using Runways 16L and R, so I had two choices: an extended right base, sticking to the north of the San Fernando Valley, or the standard, 45-degree entry onto the downwind, coming from the southern part of the Valley, following the 101 freeway. I chose the latter and began a leisurely descent to a pattern altitude of 2,000 feet for Runway 16L. I was 14 miles out.

“SoCal Approach, Grumman 29L, leaving 5,500, inbound Van Nuys.” I pulled the throttle. Nothing happened.

I pulled again. Oh no! What? The throttle was jammed. Stuck. Holy smokes! … Breathe … think.

“SoCal, Grumman 29L, declaring an emergency. We have a stuck throttle. I will troubleshoot the problem, and we will be holding over the north valley and will advise.”

“Roger, Grumman 29L. How many souls on board? How much fuel remaining?”

“Just me. One soul. Three hours,” I replied calmly or so I thought. Holy Batman! This is really happening. Keep breathing. Think.

I got over the north valley and set myself up in a race-track pattern, approximately 20 seconds or so for each abbreviated leg. “Fly the airplane” sounded in my thoughts, my instructor’s words echoing again and again. I could hear my heart pounding. Breathe. Do not panic. Keep flying the airplane.

I tried to unjam the throttle. No luck. It was just stuck. I tried screwing it apart and realized, “Idiot, this isn’t a vernier throttle!” Think. Breathe.

Doubt entered my mind. So this is the way it is going to end. Really? The doubt lasted a few fleeting seconds. No way is this happening to me. Not this way. Think.

I had plenty of fuel. All I had to do was make a short field, engine-off landing back home at Santa Monica. Simple. Fortunately, I had practiced that procedure countless times.

“SoCal, Grumman 29L, will go back to Santa Monica for an engine-out emergency landing there.” I heard my anxiety in my headset, a crack in the voice of what I had thought was my composed demeanor.

Suddenly, a new voice broke through the frequency: “Grumman 29L, I wouldn’t do that. Van Nuys is right there, and you will have a longer runway to work with.”

I didn’t know who said that. Later, I would think it was my Guardian Angel, but whomever it was, what he said was correct.

“SoCal, Grumman 29L, will make engine-out landing to Van Nuys. He is correct.” Whomever that was.

“Roger, Grumman 29L, contact Van Nuys Tower, 119.3.”

“OK, will do. Let me just get myself together.”

I was rattled. I heard it in my voice. I had almost passed up a longer runway to get back home. The dreaded “get-home-itis.”

I forced myself to take a deep, slow breath. OK. There was no other choice. Get over the airport at 1,500 feet above the ground. Pattern altitude is 1,000 feet. Give yourself some more altitude to play with. You can always slip the airplane. I could make 29L dance on one wing to lose altitude if need be.

I had over 2,500 hours in Grummans, most of them in 29L before and after overhaul and its recent 150 hp conversion, and was extremely comfortable in type. I reviewed what I needed to do once over the airport. Retard mixture. Master off. Ignition off. Maintain approach speed once established. Keep it tight, just like you practiced. OK, ready?

I turned 29L toward VNY. “Van Nuys Tower, Grumman 29L, inbound for landing. Will overfly for left downwind and cut the engine for landing.” I wanted the tower to know my plan.

“Roger, Grumman 29L, cleared to land. Any runway. Trucks standing by.” What? Trucks standing by? No way. Not today. I felt eerily calm.

I pushed the nose over. We were screaming into the yellow arc … 140 knots … 160 … almost at the end of the yellow arc … OK, 3,000 feet, that’s it. I got it down to the altitude I wanted and then crossed over the tower at midfield, starting my bank to the left downwind, keeping close and tight. My right hand now pulled the mixture control slowly toward me. The engine began to sputter and immediately lost most of its power.

But, incredibly, I realized it was still going. Of course … the throttle was still in. I had power. Eureka! I could control the power as I would with the throttle but, instead, using the mixture control. I grinned. I was going to make it.

I was descending on the downwind. Airspeed slowing, flaps coming down. Turning my base, looking at the landing point, I picked out on 16R. I was amazed. I was right on the money.

I turned final and slowed to my approach airspeed of 90 knots. The VASI’s lights were shining red over white, just right. I held my landing spot right past the numbers. Now, time to shut off the engine. I was less than half a mile out.

I pulled the mixture all the way out. Suddenly, the airplane lurched and accelerated instead of slowing down. Yikes! Of course, you idiot! The throttle is still in. Complete the shutdown checklist.

For a moment, I had a vision of a fiery crash, the firetruck’s lights flashing out of the corner of my right eye. No way, people. Not going to happen. Not this time! Master off. Ignition off. The prop came to a sudden stop.

I was a bit fast and a bit high as a result of that burst of speed. I settled down. Now I was glad I had the additional 3,000 feet of runway here at VNY. Thank you, Guardian Angel.

I held the airplane still, descending toward the runway. It was eerily quiet without the usual noise of the engine. I could hear myself breathing. Touchdown. Bounce. Hold it … hold it. We settled back down.

I didn’t even use the brakes as 29L rolled off 16R onto the high-speed exit at taxiway Hotel and slowed to a stop. In my best Chuck Yeager voice I announced, “Grumman 29L, off 16R at Hotel. Request assistance.”

“Roger, 29L. Assistance just pulled up. Look out on your left.”

There, getting out of his Los Angeles World Airports’ car, the lights flashing, was Corey Schultheis, the airport superintendent of operations for VNY, walking up to me. I pulled the canopy back.

“Great landing,” he said.

“Thanks, but I bounced it in.”

“No, great landing! You made it!”

I got out. I was not shaking. We pulled 29L off the taxiway so VNY could bring the emergency to an end. I learned later that I was a Stage 3 emergency, meaning they expected me to walk away from a crash. Not like a Stage 2. With that designation, they expect bad things. Very bad things.

Corey got a tow for 29L to Mather Aviation where it was discovered a few days later that a brass tube inside the carburetor had broken off and lodged in the butterfly valve of the throttle, thus causing the throttle to become immovable and stuck. We got it fixed, and I was back in the air a week later.

Did I do as well as I thought I would? Further debriefing with my flight instructor and also with a Delta airlines pilot I met gave me more pause for reflection.

I did pretty darn good for an infrequent aviator. My years of flying experience and all the short-field landing practice in 29L paid off. However, I could have lingered more over the Valley at altitude when first troubleshooting and thought it through more, where I might have discovered that the mixture control was going to be my throttle control.

I had a brief flirtation with “get-home-itis.” Not good, but corrected when I heard the fellow concerned pilot on frequency. I was more nervous than I thought. My anxious voice was an alarm to me. Yet I still patted myself on the back. I had lived to tell this tale.

If there is a next time, I know now that I should pause to think even longer. Breathe more deeply. Slow things down. Fly the airplane. Visualize and think more about what is going to happen and what I should do.

I instinctively knew what to do and just did it. Had I thought it through more, well, maybe I wouldn’t have declared an emergency so quickly and would have discovered that my mixture was my throttle, or maybe I would have been more relaxed and less in shock in order to get down more calmly and less dramatically. Maybe.

As with every flight, we learn something about ourselves as pilots, as people and as the ultimate commanders of our fate.

I returned to my house that evening and, with a glass of Macallan single-malt whisky in my hand, stared out at the Pacific Ocean and watched the sunset end Independence Day. I had come face to face with the possible end and survived.

Of course, I hope this will be my last mechanical failure for the rest of my flying days.

Meanwhile, I will continue to maintain my discipline, keep current, practice those short-field landings — and remember to breathe. And breathe again.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox