Those are the two words that can change a life, disrupt a business or curtail a profession forever! I heard them unexpectedly from my FAA medical examiner of several decades, Dr. Ed Klemptner, in July, just a few weeks after my 80th birthday.

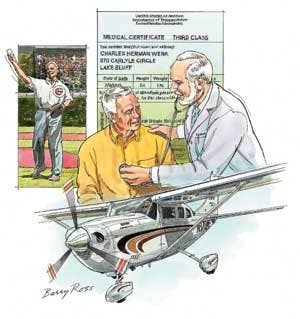

The actual birthday started out in great fashion. I had nixed the idea of a big party with all my old friends (those that were still ticking!), clients and relatives. Happily, my son, daughter and wife, Gail, all pilots, arranged a spectacular substitute. I would throw out the first pitch at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

I had several weeks to practice as I hadn't thrown a pitch in years. My next-door neighbor had a catcher's mitt and I still had my old high school fielder's mitt. By July I had regained whatever form I had in my teens and when the day arrived, a beautiful, cool July day, I managed to throw the pitch right down the pipe and into the catcher's glove 60 feet away. There was some celebration THAT night.

Two weeks later Chicago had what would be the warmest day of the year. It was 105 degrees in the shade! The week before I had proudly bought a frame for my 10,000 hours of flight time certificate from the NBAA and hung it in our office. I had zero medical history, never took any pills or medicine, and the only time I had ever been a patient in a hospital was as a kid of about six for a tonsillectomy.

However, on that torrid day I suddenly fainted for the first time while running with my Irish Setter. Although I popped out of it minutes later, my wife insisted I go to the emergency room at nearby Lake Forest Hospital and that was the beginning of the end, temporarily.

While I had no specific heart problem I had a very slow heartbeat. About 35 at rest, when it should be 65 or 70 beats a minute. The examining physician at the hospital, Dr. Jay Alexander, a well-known cardiac specialist, told me I had no other symptoms following several stress tests and an angiogram.

I spent three days in the hospital taking those tests and Dr. Alexander gently advised that although the great athlete Jim Thorpe and bike champ Lance Armstrong had similar heart rates, they weren't 80 years old when it manifested itself.

To make a long story short, the doctor strongly recommended a pacemaker be installed to prevent further complications and help me avoid light-headed situations. It didn't hurt at all and I did indeed feel better. I knew I had to call my FAA medical examiner. I was told that several hundred pilots, many of them corporate and charter captains, had pacemakers and were still flying actively with third- or second-class medicals. Doc Klemptner advised: "Don't worry, Chuck, you'll have your medical back within six months but it'll probably be a third-class one. I'll work on it for you."

So I was grounded. At 80, I was still working a full day at the office. We have the oldest aviation insurance specialty house in the country, started by my father, Sam Wenk, in 1932. He had been a pilot in World War I and I spent three years overseas in World War II. Flying is in the blood of my family and that of my wife, who finished last twice in the Powder Puff Derby. (Now I'll need the pacemaker!)

We had sold our company's 58 Baron a few years back, and I had purchased a new, sleek Cessna 206 that is perfect for a senior citizen like me and for my daughter, who works in the agency and just flies a few hours a week calling on clients.

For five months I would drive to my home base and hangar at Kenosha, Wisconsin, pull the Cessna out and wash it. It was almost overgross with wax. I attended airport board meetings and stayed active on the Illinois Aviation Advisory Commission, but just didn't have my past enthusiasm. I had to attend aviation seminars in Milwaukee and Springfield, Illinois, that involved driving many hours instead of the short flights of the past. Meanwhile, I gathered tracings of all my hospital tests and sent them to Dr. Klemptner for forwarding purposes to the FAA. I rarely told anyone I had blown my medical.

Finally, in late January of this year, I heard from the FAA in Oklahoma City. They sent me a form to complete, letting them know what kind of flying I planned for myself if my license was restored. I wanted them to know that if they gave me the medical back I would rarely fly at night, I would rarely fly on instruments in poor weather and would only get in the aircraft in severe, clear weather and on trips of less than two or three hours. Just give me the darn thing back, guys, and the pacemaker and I will shoot touch- and-goes for five hours until I leave the airport pattern. (Honest.)

A week later I got another communication from Oklahoma. With it came the renewal of a third-class medical and the only task I have is to send tracings from my pacemaker every six months for a year. Fair enough.

I have seen pilots lose their medical and give up on ever getting it back. As I write this, I am en route to birthday 81 and I feel just great. One of my pilot clients, also a physician, advised me that I was lucky because when I finally die, my pacemaker will continue to keep working. I don't know how I feel about that.

The purpose of this review, though, is to let other pilots know there is always a chance to get reinstated and that they should never give up or go out and buy a Chris-Craft. Ask your own medical examiner to do the paperwork for you because they will do it properly. They should write to the Aeromedical Certification Division at the FAA Civil Aeromedical Institute, Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center, P. O. Box 26080, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73126-9922. I'll cross my fingers for you. Good flying, stay healthy.

To see more of Barry Ross' aviation art, go to www.barryrossart.com

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox