The evolution of technically advanced aircraft in the early 21st century brought primary flight displays and their vast wealth of information to general aviation aircraft such as the Cirrus SR20 and SR22. Tim Barker

It doesn’t much matter whether Boeing intended to set off a revolution in cockpit instrumentation when it delivered the first 767 in the early 1980s. That, of course, was the result when the new jetliner unleashed the first computerized cockpit displays destined to forever change the way pilots control and navigate aircraft. The new instrumentation quickly came to be called the glass cockpit.

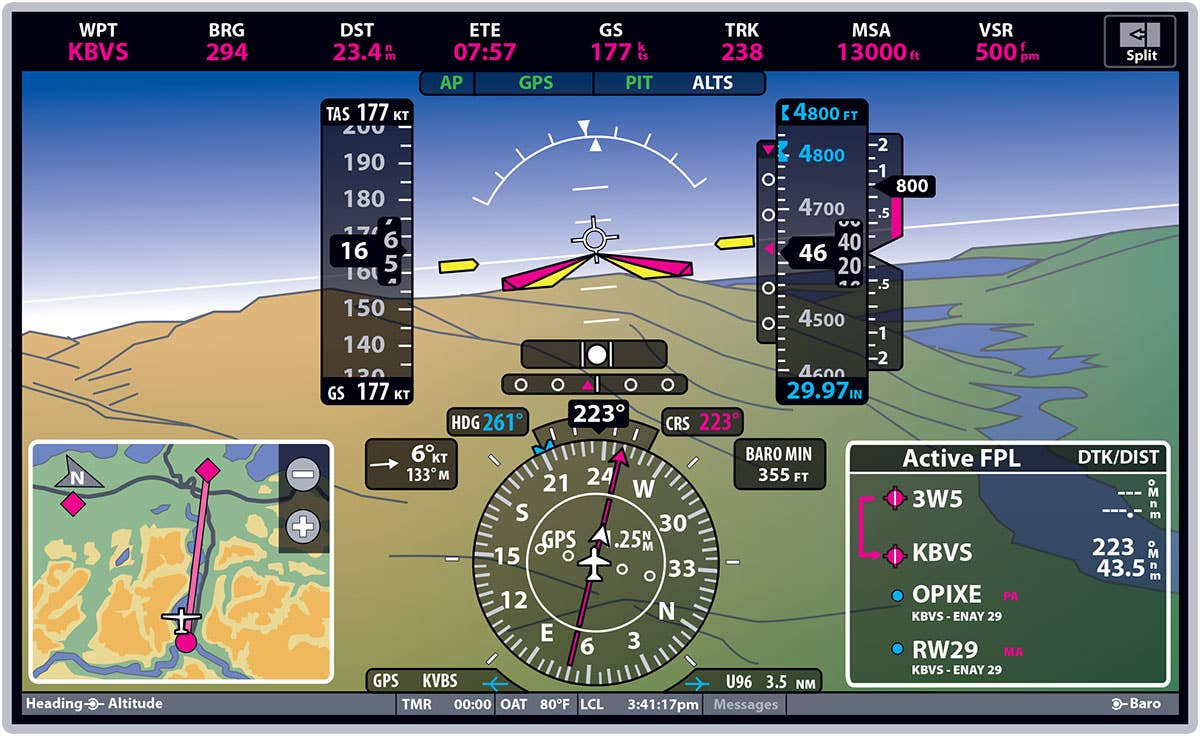

Round flight instrument gauges usually organized in two rows of three instruments each were replaced with computer-generated graphical representations of an attitude and heading indicator, as well as those for airspeed, vertical speed, turn coordinator and altimeter. Not only were the new instruments more efficiently organized to present information on the CRT screen used to display them, but they also added color and movement where none had existed before. The central CRT came to be known as a primary flight display. Additional CRTs were used to show important navigation and weather information on what became known as multifunction displays.

The evolution of technically advanced aircraft in the early 21st century brought PFDs and their vast wealth of information to general aviation aircraft such as the Cirrus SR20 and SR22. Most other major aircraft builders quickly followed suit with their own glass cockpits. Today, it is pretty much impossible to buy a new high-performance airplane from any of the big original equipment manufacturers that is not equipped with glass instrumentation.

Glass flight-instrument displays are usually fed by many of the same data sources as the old round gauges, such as pitot tubes and static ports. The difference now is that a PFD uses a computerized signal generator to translate that data into visible images, much the same way colorful, animated games are created for personal computers. One huge advantage of a PFD and its associated equipment is that these systems are created with few moving parts, which makes them highly reliable.

The PFD revolutionized pilot training as well as aircraft control. Years ago, pilots earning an instrument rating were taught a basic instrument scan, a procedure to ensure the PIC was aware of even the slightest heading, altitude, or airspeed trends or changes. These efforts often kept a pilot’s head moving most of the time, often causing fatigue.

The PFD’s graphical world displays all the necessary flight information in a format that much reduced the need for that constant left-right, up-down scan. The PFD not only made fixating on one instrument less common, but the entire system helped reduce a pilot’s overall workload, once their eyes became used to seeing the information presented in a new format, of course. In the early days of the Boeing 767, there were some pilots unable to make the leap from the old round gauges to a glass cockpit.

When a pilot views the attitude indicator on a PFD, for example, the new colorized symbology makes it easier for a pilot to determine the aircraft’s airspeed, heading, altitude and vertical speed at almost the same moment. No need to interpolate an airspeed as somewhere between 120 and 140; the PFD shows it as precisely 133 knots, or an altitude at 5,750 feet.

In addition to the PFD’s color graphics and precise digital displays, the new instrument displays began showing information vertically, a change that made trends easier to track. Navigation information was also incorporated into the PFD, with the localizer needle shown just beneath the attitude display indicator. The glideslope ran vertically to the right of the ADI. Even the turn coordinator was neatly added at the top of the ADI, making it easier to be included in the pilot’s instrument scan for more-precise aircraft control.

As major avionics manufacturers such as Garmin, Honeywell, Rockwell Collins and Avidyne continued improving their products, pilots noticed the addition of useful figures, such as best angle or best-rate-of-climb speeds, that traditionally would have been committed to memory. Most new attitude indicators now offer pilots graphical guidance to assist with recovery from an upset condition, airborne traffic and even weather information.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox