The APU is a small turbine engine installed near the rear of the fuselage. Honeywell

An aircraft auxiliary power unit serves as an additional energy source normally used to start one of the main engines on an airliner or business jet. The APU is equipped with an extra electrical generator to create enough power to operate onboard lighting, galley electrics and cockpit avionics, usually while the aircraft is parked at the gate. Drawing bleed air from its own compressor, an APU also drives the environmental packs used to heat and cool the aircraft.

And most important, operating an APU negates the need to start one of the aircraft’s main engines while waiting for passengers to arrive, thereby saving on fuel and maintenance for a more expensive power plant.

In most cases, the APU is shut down before takeoff and reignited when the aircraft clears the runway after landing. While most of an APU’s active service life occurs as the aircraft sits on the ground, in some instances the APU is used as an emergency electrical power source while the aircraft is airborne.

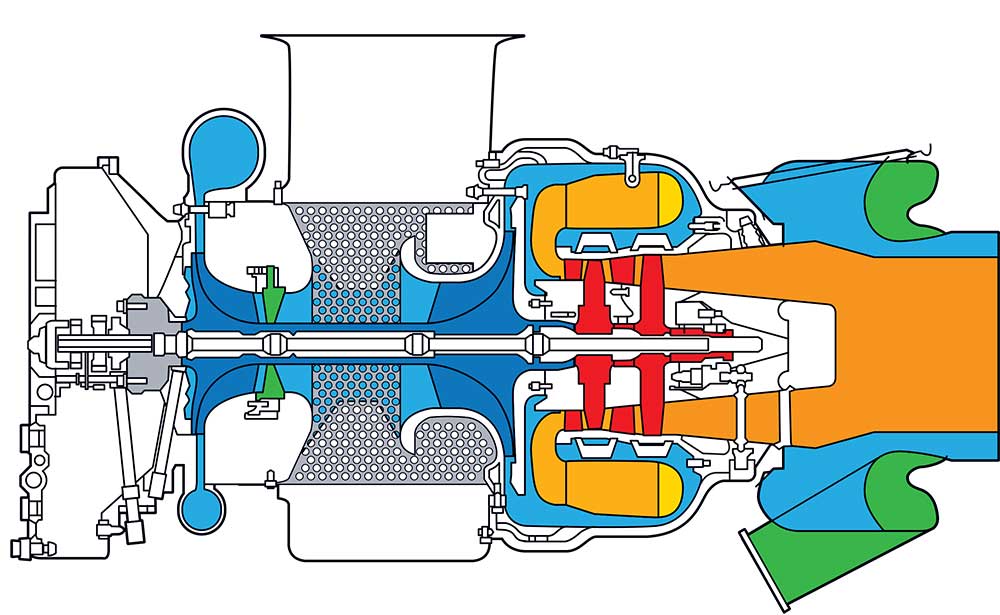

The APU is a small turbine engine installed near the rear of the fuselage. But calling the APU an extra jet engine is not accurate because the turbine exhaust from the APU is vented overboard. A jet engine would be used to propel the aircraft forward.

The earliest APUs could be found on the B-29 Superfortress, looking essentially like a motorcycle engine installed inside the fuselage. The Convair XP5Y-1 also used an early APU, while America’s first jet airliner, the Boeing 707, was delivered without one. The 727 was the first Boeing to be APU-equipped.

Today, APUs can be found in medium-size and larger civil and military jets, some turboprop aircraft and a handful of military fighters. Smaller civilian jets like the Cessna Citation CJ or One Aviation’s Eclipse jet don’t carry an APU because the extra weight of even a small extra turbine engine can significantly impact the airplane’s useful load.

The aircraft manufacturer determines APU requirements after considering the size of the cabin, the amount of bleed air required to power the environmental packs, and the generator size needed to power the cockpit and cabin and start an engine. It is then the job of the APU manufacturer, usually a subcontractor to the aircraft manufacturer, to deliver a unit meeting those specifications.

While readying the avionics is an important element of preparing an aircraft for departure, creating a comfortable cabin environment before passengers arrive is almost more important to most operators. During hot summer months, the APU driving the environmental packs might require half an hour to cool the cabin of an aircraft sitting in Miami, and equally as long to heat one in winter on the ramp in Fargo, North Dakota.

During some extended-range twin-engine (ETOPS) flights, which permit twin-engine aircraft to operate on routes more than 60 flying minutes away from a suitable emergency airport, the APU system must be tested — using a cold-start procedure — to verify start reliability in case it might be needed, should one of the aircraft’s main engines fail in flight.

One drawback to APUs is the noise they often produce while running on the ground. In some older aircraft, the noise of the APU’s turbine engine can become worse once the bleed air is switched on to heat or cool the cabin. A number of airports in the United States still restrict the operation of APUs, especially at night, to avoid annoying people in nearby communities.

Like all modern turbine engines, an APU is equipped with a fire-extinguishing system, often operated automatically in newer aircraft. Those operating an APU without automatic extinguishing systems usually require at least one pilot to remain near the aircraft in order to hop aboard and manually discharge the APU fire bottle should a blaze erupt.

Unlike the aircraft’s main engines, which require regular tear-downs at very specific time points for maintenance, many APUs are treated more like pass/fail items, allowing operators to run them until something breaks, unless, of course, the unit is part of an ETOPS operation.

In days past, when the price of jet fuel was considerably more expensive than today, some airlines were known to wait until just before departure time to start the APU in order to save money. Luckily, for passengers at least, that strategy to economize was quickly superseded by passengers’ demand to board an aircraft with a comfortable cabin.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox