Honeywell Crafts Safer Approaches Through Technology

Aerospace giant has expanded its navigation database to offer FMG-guided visual procedures as a stand-alone option.

According to Jim Johnson, Honeywell’s senior manager of flight

technical services, the company’s FMS visual approaches

are created in collaboration with Jeppesen. [Adobe Stock]

“Can you accept the visual?”

It is not uncommon for air traffic control to pose this question to pilots on IFR flight plans approaching certain airports when the weather is VFR. In daylight, when the visibility is good, the winds calm, and the pilot familiar with the airport—and the approach is a straight in—the visual is no big deal.

But throw in weather, fatigue, low light, pilot unfamiliarity, and a circle to land, and it’s a different event.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowHoneywell Aerospace is trying to mitigate these risks, expanding its navigation database to offer flight management system (FMS) guided visual procedures as a stand-alone option.

According to Jim Johnson, senior manager of flight technical services at Honeywell, the visual approaches are created in collaboration with Jeppesen. The instructions for the guided visuals look like Jeppesen approach plates but carry the caveat “advisory guidance only” and “visual approach only.” In addition, the symbology on the approaches differs in a handful of ways.

“The FMS-guided visual provides a lateral and vertical path from a fix fairly close to the airport all the way down to the runway,” says Johnson. “You can hand fly them or couple them to the autopilot.”

Visual into KTEB

One of the first guided visual approaches was created for the descent to Runway 1 at Teterboro Airport (KTEB) in New Jersey.

The airport sits in a very industrialized area with the runway blending into warehouses and business parks. Honeywell provides a video of the visual approach on its website that illustrates the value of having that helping hand. Having the extra vertical and lateral guidance from a mathematically created visual procedure allows pilots to better manage their approach, configuring the aircraft in an expedient manner to avoid “coming in high and hot” in an improperly configured aircraft.

This is quite helpful when the aircraft needs to circle to land, says Carey Miller, pilot and senior manager of technical sales at Honeywell.

“Going into Runway 1 at Teterboro on the visual, you are not aligned with the VASI,” Miller says. “There is no vertical guidance, which can lead to a dive to the runway. Add a moonless night or gusty winds, and it can be quite challenging. Not being able to see the airport is a detriment to your energy management. The visual approaches, when coupled to the autopilot, eliminate the guesswork and the overbanking tendency that can lead to stalls.”

Adds Johnson: “The aircraft will fly constant radius turns, [and] you will be on the same ground track every time because the computer knows how to manage the vertical and lateral path. It gets rid of the pilot drifting down or turning early because of the winds.”

Airspace Guidance

The guided visual procedures created thus far have come from suggestions from Honeywell customers, including a visual approach to Chicago Executive/Prospect Heights Airport in Wheeling, Illinois (KPWK). KPWK is in Class D airspace, 8 nm from Chicago O’Hare International Airport (KORD). The Class B airspace for KORD sits above KPWK. There is a V-shaped cutout with various altitudes over KPWK.

The guided visual can help the pilot avoid clipping the Class B airspace during the circle to land—and the dreaded phone call with ATC that results.

The Creative Process

Each approach is created using software tools that take into account the airspace and terrain at the airport, then test flown in simulators to check for flyability.

According to Johnson, the suggestions for where to offer the guided visual approaches come from their customers.

“There are a lot of secondary and regional airports in the U.S. that have both terrain and airspace considerations that make visual approaches very challenging,” says Johnson. “For example, Van Nuys, California [KVNY], has both airspace challenges and a ridge nearby.”

- READ MORE: All Flight Jackets Tell a Story

In some cases, the team may opt to create a visual approach as an overlay to improve safety at airports where closely spaced simultaneous approaches are in use. As this issue was going to press, Honeywell was working on an approach to Runway 28R/L at San Francisco International Airport (KSFO). The visual approach has a briefing sheet with textual guidance, and Honeywell has literally drawn a picture of it.

During development each procedure is flown in a simulator, using a specific briefing sheet that is checked and double-checked for accuracy and usability. Each approach has the ability to be coupled with the autopilot.

Miller cautions it is important to recognize that the visual procedures are not considered instrument approaches in the traditional sense.

“Do not request it as an approach, because ATC will not be aware of it,” Miller says. This information is emphasized on the procedure briefing sheet that accompanies each guided visual approach.

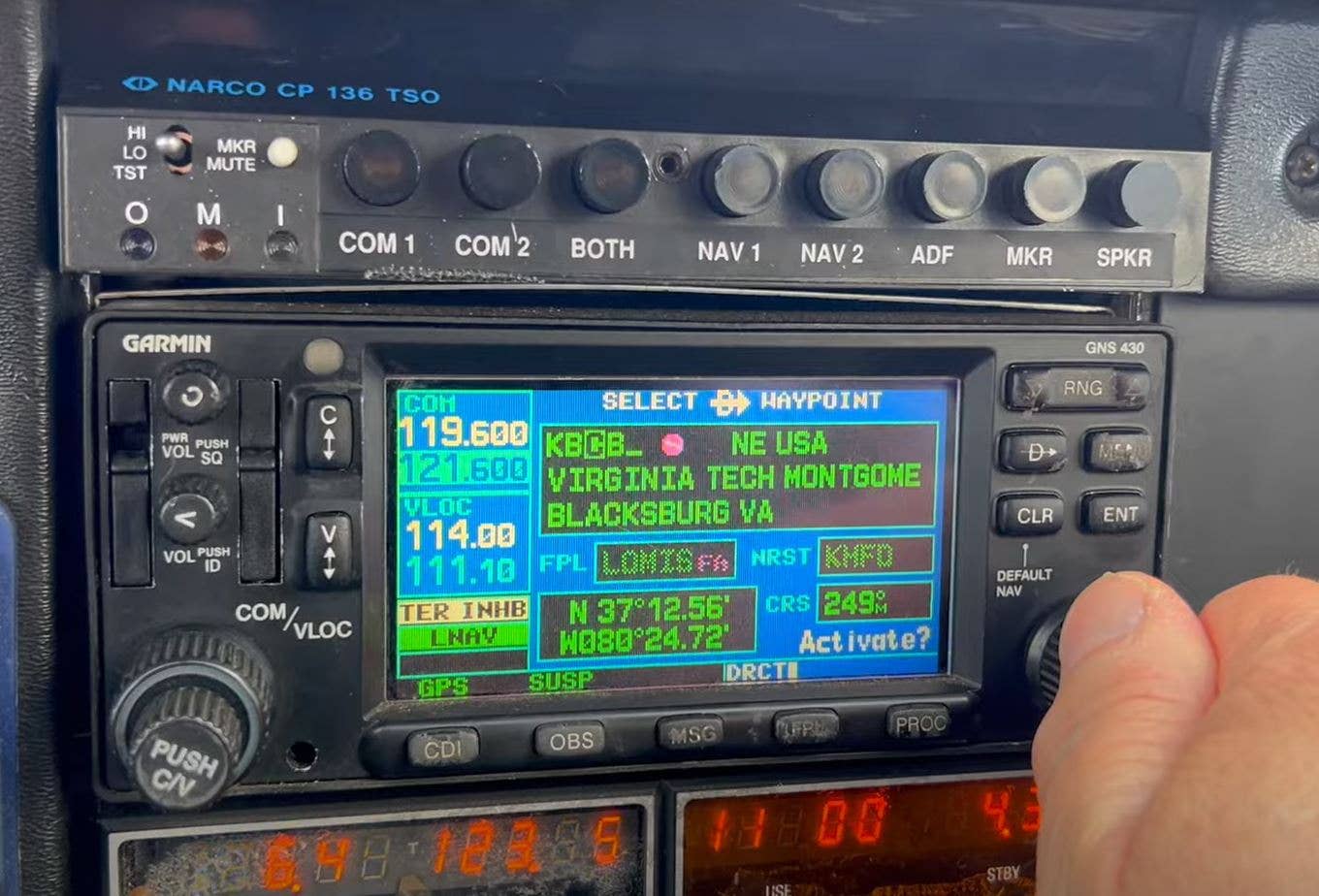

The guided visual approach is loaded in the FMS just like an instrument approach. The pilots can access them with a few pushes of a button, just as they do Jeppesen approaches.

“To use the visual approaches, the customer needs to have a Honeywell-equipped aircraft, and in addition to the FMS database, for an additional $2,000 per year they receive the visual approaches,” says Miller.

To request an approach, contact Honeywell at FTS@honeywell.com. It takes approximately four weeks to put one together.

Coming Full Circle

In many ways, the visual approach procedures represent a modern treatment to the first approaches created by Elrey Jeppesen—yes, that Jeppesen—who became a pilot in 1925 at the age of 18. At the time, there was no such thing as maps purpose-built for aviation. Pilots relied on road maps—which often weren’t terribly accurate, following railroad tracks from town to town or by pilotage and dead reckoning.

In 1925, Jeppesen went to work as a survey pilot and by 1930 was working for Boeing Air Transport, the precursor to United Airlines. This was decades before air traffic control and electronic navigation systems were created. Jeppesen bought a small notebook and filled it with information about the routes he flew. In it there were drawings of runways and airports and information that pilots needed to know, like the elevation of water towers, telephone numbers of farmers who would provide weather reports, and dimensions of the runway and its distance from the nearest city.

In 1934, this evolved into the Jeppesen Company and the notebook into the en route charts and terminal area procedures we know today. Much of Jeppesen’s flying was done in the Pacific Northwest. The Museum of Flight in Seattle is the keeper of the Elrey B. Jeppesen Collection, and for many years there was a replica of his first notebook on display in the Red Barn.

We think Captain Jepp would appreciate how far the approaches he inspired have come.

This column first appeared in the January-February 2024/Issue 945 of FLYING’s print edition.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox