Flying Blind: Trust Is the Cornerstone for This Alaska Air Rescue Team

“What we didn’t want to do was leave him up there for another couple days, because he would have died,” the pilot of an Alaska Army National Guard Medevac flight told FLYING.

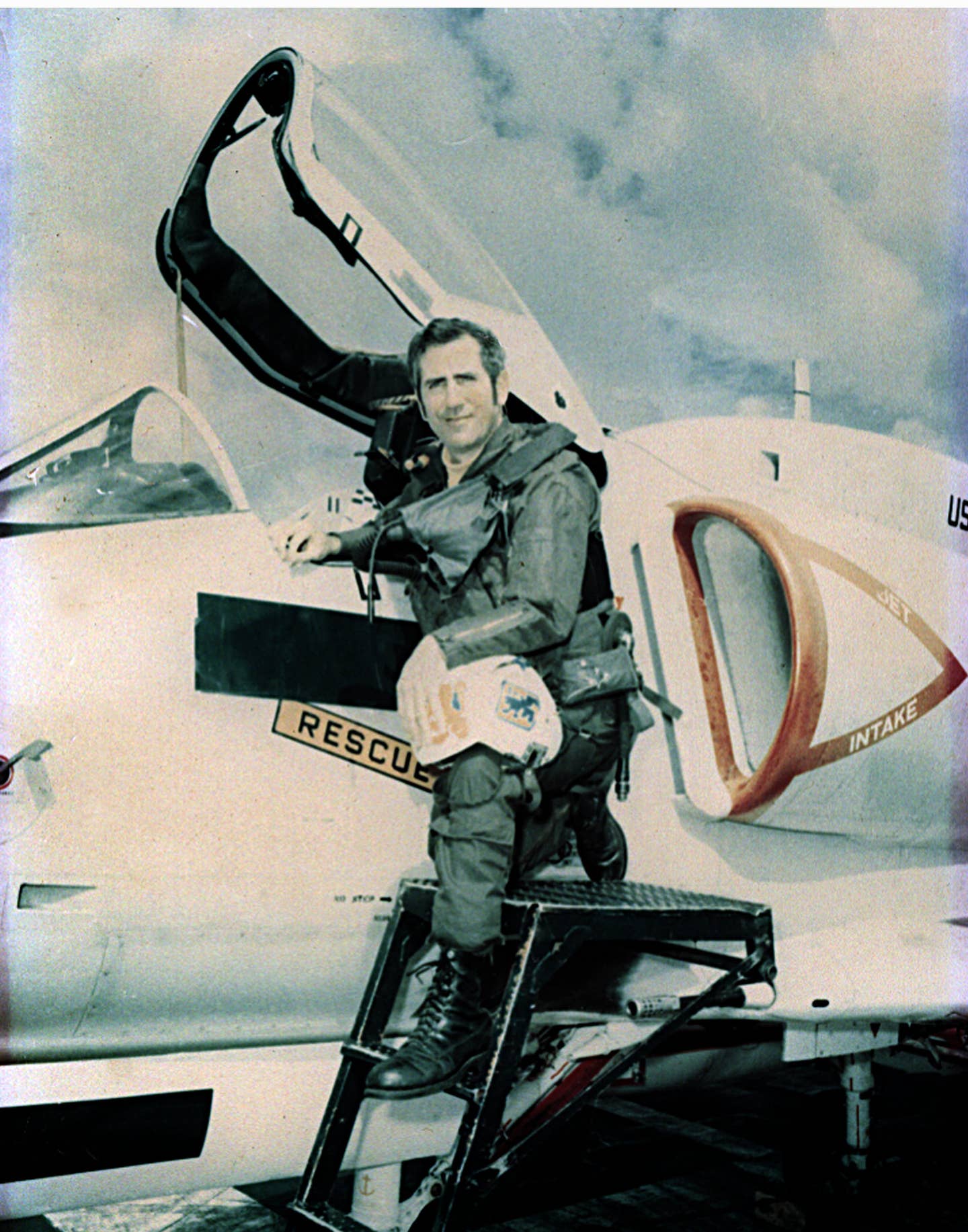

The rescue earned the team the 2021 Rescue of the Year by the DUSTOFF Association. [Courtesy: Capt. Cody McKinney]

Every year, more than 450 search and rescue (SAR) operations are conducted in Alaska, according to Alaska State Troopers, the statutory lead in all SAR efforts in the state. For more than 20 years, the Alaska Army National Guard has been one asset troopers have relied upon for assistance in remote SAR operations.

Last September, troopers turned to Alaska Army National Guard's Golf Company, Detachment 1, 2-211th General Support Aviation Battalion, 207th Aviation Regiment for help. Medevac Commander and UH-60 Black Hawk Instructor Pilot Capt. Cody McKinney, along with flight medic Sgt. 1st Class Damion Minchaca and helicopter crew chief and hoist operator Staff Sgt. Sonny Cooper were part of a four-person team dispatched to try to rescue a sheep hunter who had been stuck on a ledge for two days. A snowstorm was moving in, and time was running out.

The rescue earned the team the 2021 Rescue of the Year by DUSTOFF Association. Here is their story, as told to FLYING, of that day, how they performed the daring rescue in their UH-60 Black Hawk during treacherous whiteout conditions, and the teamwork and trust it required among the crew. Their conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and space.

Capt. Cody McKinney, Medevac Commander and UH-60 pilot

In this [rescue], particularly, they called us, and I think it was 2 in the afternoon, and said: “We have a hunter—he was hunting sheep—and he got stranded on a ledge that we think is about [a slope of] 60 degrees, and he's up at 5,800 feet. And he's been up there for at least two days. He can't move anywhere. We don't think he has any injuries. But he may have cold-weather injuries, given how high he was, and it had snowed the last two days.”

When we received the mission, the first thing we did was we started flight planning. We knew that he was at 5,800 feet, and we knew that he was on super steep terrain, so we kind of knew what kind of hoist it was going to be. But then, when we started looking at the weather system, they were showing a broken ceiling somewhere in the 4,000s [feet].

We had an idea that we weren't going to be able to get up to him, but with a broken ceiling, we figured we would try.

We launched pretty quickly after receiving the mission. We were going toward Knik Glacier, I think it was a 30-minute flight.

We climbed as high as we could, and we started bumping up against the clouds. I want to say we were [at] 4,500 feet or so with a broken layer. As we were doing that, we're like, "We're not going to be able to get to this guy. So what can we do?"

We called back to our boss and asked her to get the Alaskan Mountain Rescue Group on the phone and pre-position them in Palmer [Alaska], which is about 15 miles away from the rescue site.

“Do you, or someone you know, have a unique story of flying while in uniform? Tell us about it! ”

Our plan was, we're going to go out there. We're going to try to see if we could get to him, kind of anticipating that we couldn't. [If so,] then we would swing back, try to find a good place to land up there as close to him as we could get. Then, we would come back and pick up Alaska Mountain Rescue Group guys, put them in via hoist as high as we could get and let them climb up to him. Then, they could bring them back down and we would hoist them out, you know, so we weren't trapped in that cloud layer.

What we didn't want to do was leave him up there for another couple days because he would have died.

We're coming up with this plan, and what we try to avoid is a quiet cockpit. So one thing we've kind of learned over the last three or four years working together is when a cockpit gets quiet en route, we just try to start talking about things that maybe we're forgetting.

So, we said, “All right, we know this guy's been up there, he's hunting, he's got a lot of money. I bet you this guy isn't gonna want to get on the hoist without all of his gear,” which is a thing. These guys get all combative and weird because they spend thousands of dollars on that gear, which we're not interested in at all.

So [Staff Sgt. Sonny Cooper] says to [Sgt. 1st Class Damion Minchaca], “Hey, I'm going to hook you up with extra carabiner. Like, we'll get you the two-up device from Air Rescue systems and we'll have everything in place in case this guy refuses to leave so that we can at least do a quick pick.”

When we got around the corner to start looking at lower elevation places we could land, we found an opening in the clouds that we thought we could punch up to. When we saw that, it was kind of like a reality check between the crew. Do you guys want to come up to this and actually do this? We're surrounded by 7,000-8,000-foot mountains.

If we come up through this layer and we get stuck, we're gonna have to push up through the icing and all the clouds to try to get an IFR clearance back, and it's going to be a significant emotional event for everyone. But, you know, that's the nature of medevac missions and we wanted to get this guy back home.

We decided to push it.

We came up through this hole—I think it was 4,500 to 4,800 feet—there was a layer where these broken clouds were sitting at, that 4,800-foot layer. We couldn't really see it, but we knew that there was a ceiling at about 6,000 feet, and it was snowing pretty heavily.

We got the grid where this guy was supposed to be, and of course, we couldn't see him. And so we're trying to fly around, and I'm telling my pilot in the other seat, “If you lose the mountain out the left side, let me know so that I can start to descend, or we're gonna push up and start climbing because at that point, I think visibility was probably a mile.”

Very similar to flying in a ping-pong ball. We were using the broken rocks on the side of the mountain as reference points. We did two orbits looking for this guy and he finally figured out that there was a helicopter in front of him. He had a jacket that was red on the inside, and he turned it inside out and waved it at us, so we saw him.

Winners! Alaska Army National Guard aviation wins DUSTOFF Association Rescue of the Year! #TeamAKNG #AKArmyNationalGuard #dustoff

— AlaskaNationalGuard (@AKNationalGuard) February 18, 2022

Story here https://t.co/GBzGt7kUN5 pic.twitter.com/ucgARAqB0R

What he had done was he came off a saddle and scurried across a little scree field with a 60-degree slope, and then got caught on this little rock ledge that was maybe 3 feet by 3 feet. And then it snowed while he was there while he camped overnight. The next morning, he was just stuck. He couldn't go anywhere.

We identified him, knew where he was at and knew it was going to be a very technical hoist. We did an orbit and just talked about, “Hey, this is what we're going to do. We're going to do a dynamic-style hoist. We're going to minimize our time coming in. And then after we pick him off the hoist, we're going to do a left descending turn, and while [Minchaca's] coming back up into the helicopter, we're going to descend back down through that sucker hole to make sure that it doesn't close up on us.”

We came out maybe a quarter mile from where he was and we did all of our safety checks, opened the doors [Cooper] moved out to the door of the helicopter and brought [Minchaca] out.

We have skis on our helicopter, so you actually have to drop half of our ski when it kind of dangles down below so that the hoist rider doesn't hit it. Then we brought [Minchaca] out to what we call the brace position, which is where we bring the cable down and he sits basically where the floor of the helicopter sits at his armpit level. And then we kick the tail out to the right about 15 degrees, so we're flying in kind of like a notch profile. What this allows is for the hoist operator and the hoist rider to visually confirm the target and to make sure that everybody's on the same page of what we're doing and where we're going.

We are in that profile with the nose kicked to the left about 15 degrees. We're going about, I don't know, 50 knots-ish, and we're starting this kind of gradual approach to him.

[Cooper], in his head, is measuring where the target is at so that he times running the cable out.

Staff Sgt. Sonny Cooper, helicopter crew chief and hoist operator

At this point, we've identified the target. The aircraft is in its profile and we're on approach but this guy put his jacket back on, the camo side out. I was the only one who actually had eyes on him at this point, so I'm trying to guide the aircraft in while trying to point him out to [McKinney], who is on the controls in the right seat and also point him out to the medic because we don't really have the time to do more orbits in there and find this guy.

This is our one shot, our one chance to actually get to him in a timely fashion.

We're making the approach and calling him in, and about halfway in, [McKinney's] able to identify him. [Minchaca] gets eyes on him and I start rolling the cable out. I'm lowering [Minchaca] down. I'm waiting for his hand and arm signal letting me know that he's about the same level as the guy on the mountain.

"This is our one shot, our one chance to actually get to him in a timely fashion."

Staff Sgt. Sonny Cooper, helicopter crew chief and hoist operator

He gives me a signal, so I stopped cabling him down. I continue calling the aircraft in until [Minchaca's] within five feet of the target. But, I'm looking down there at this guy and he's on this small ledge that's maybe 3 feet wide by 2 feet back and there's a wall of rocks right behind him. There's nothing but snow on either side of him, to his left and right. I'm not wanting to set [Minchaca] down right on top of this guy because there's a risk of bumping this guy off the mountain.

At first, I tried setting [Minchaca] into the snow on one side of him. The snow sloughed out from under him, so I tried the other side of the guy and set him down. That snow was just as soft and nothing stable to put [Minchaca] on, so my last option was to put him basically right on top of the guy.

When [Minchaca] landed, his feet basically interlocked with him.

Keep in mind this is all probably within about 30 seconds. I tried one spot, tried the other, and they don't work, and I put him right on the guy.

Capt. McKinney

I think at this point, too, the cable length is probably 70-80 feet. We like to hoist at no lower than 70 feet because the rotor velocity on the helicopter is so great that it will affect the hoist rider. We also didn't want the downwash from the rotor system to push that guy off that ledge.

Like [Cooper] just said, [Minchaca] tried to touch a part of the ground that was next to him and it just completely shuffles, like sloughed off. It was a good thing he didn't try to walk out because it would have killed him.

This terrain relief was 60 degrees or so. When we ran [Minchaca] out on that cable initially, we're at 5,800 feet and all the way down to the bottom of that valley. He was sitting out there, just dangling for 30 seconds at 4,000 feet or so.

Sgt. 1st Class Damion Minchaca, flight medic

When I came out of the helicopter…and I didn't see the guy. I finally get a little glimpse of the guy but I keep losing him. I'm really trying to work the wind because, as we're coming in, we have to beat our rotor flow. We try to beat that before it starts to make you spin. I come down and me and Cooper, we're working together. I'm near the area I want to be at, but I touch it and [what looked like snow covered ground] obliterates. I thought it was solid. I felt like I was going to fall off the face. It was pretty intense.

Before we got out there, me and Cooper actually did a little practice run of how we're going to use the ARV—our air rescue vest—in the back of the helicopter, so I was ready and pretty prepared to get him inside of it.

I push him against the ledge to get a nice and stable base. He was already on top of it. He's screaming about his hunting bag before I can talk to him about anything else. I was like, “Hey, just hold on. Let me get this vest on you.” I throw his arms through the vest, get him locked in. I get all three points locked in, and I reach over and grab his hunting bag.

[Minchaca informs the man that if the bag hinders the operation in any way, it will be left behind.]

I look up and you can see the helicopter, all the snow, it's breaking the mountain apart as we're trying to get off of there. I just knew we had to get out of there right away. I snapped it on. I get the up signal, so I shook my head up and I'm ready to go. And I come right off that mountain.

When we do those swings, as you come off the mountain, the helicopter turns into the swing, and it is a perfect flow as we're coming through. We came up nice and straight. We didn't spin at all and came right into the cabin.

Capt. McKinney

One of the interesting things about the medevac and hoists and a helicopter that's over 70 feet long is that—like typically in aviation—it's always the pilots who have the precision and the skill and all that stuff. But in hoists and these precision environments, it's really a team effort.

The way that [Minchaca] rides the hoist, like if he puts an arm out in the wrong position and gets into a spin. If he doesn't give the right hand and arm signals, we put him down in the wrong spot. But we know we're 70 feet in the air coming down to a target that I can't see, so it becomes like this trust game.

[Cooper] is not only working a pendant that goes up to 300 feet per minute, trying to manage [Minchaca] and talk to me about what's happening on the hoist. He's also calling the helicopter, and I am just blindly trusting whatever he says.

So if [Cooper] says, "Hey, you're clear left, I want to bring that tail around and start to move left and descend," I just do it because I trust him.

That's kind of the environment that we've built here. It just absolutely does not work unless you have that.

When we started bringing [Minchaca] in, because you have the rotor velocity coming off of the helicopter, it comes down on that slope. And as it's coming down on that slope, it doesn't matter how good a pilot you are. As soon as you pick that load up, that velocity is going to push that load away from the mountain. The only way that you can manage that is that you time it and you roll the helicopter away with it to stop any unwanted conical rotations.

[Cooper] was managing all of that stuff. He's also, in his head, timing as we roll out. Then, as we're turning around the corner, we're descending into a cloud layer, and we're looking for that open spot.

As I'm coming right, my co-pilot [Chief Warrant Officer 2] Brad Jorgensen says, "Hey, you got an opening right there. Let's straighten it out." Cooper's saying the load is good, bring him up. In a matter of two minutes that felt like an eternity, we pick this guy off of a mountain. We've got him. We brought him back in the helicopter. We descended back through a cloud layer and we're headed back.

The reason that these missions like this are possible is because we have the support of our leadership to train in technical environments, so when we go and we do a hoist off the mountain, it's not like the first time we've done it. We have the Air Guard and other DOD assets that we train with, the Air Force. We've trained with the [Navy] Seals up here, [Special Forces] teams. We have this high level of proficiency so that when we go out and somebody is relying on us to bring their kid home that they can have the trust, and we have the fidelity to actually execute those missions.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox