‘Thunderstorm of the Worst Case’

An Air Force C-17 Pilot Recalls Leading the Last Formation of the Afghanistan evacuation.

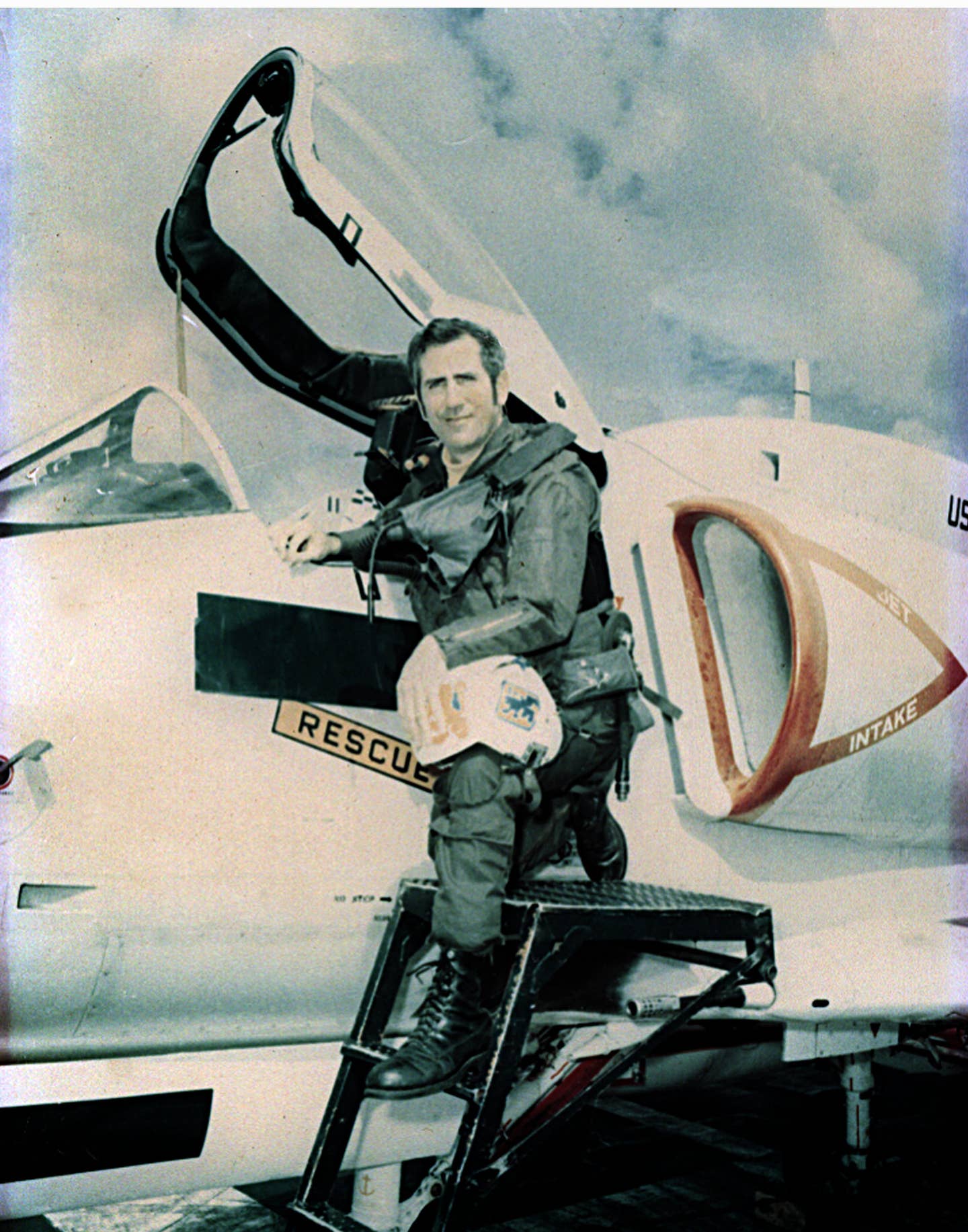

U.S. Air Force C-17 pilot Major Kirby Wedan [Courtesy: US Air Force]

Editor’s Note: On August 30, 2021, the last round of U.S. military airplanes filled with troops and civilians departed Kabul, marking the end of the U.S. war in Afghanistan. During the Noncombatant Evacuation Operation (NEO), military flights evacuated an estimated 124,000 people from Afghanistan. U.S. Air Force C-17 pilot Major Kirby Wedan led the last formation of aircraft out of Afghanistan. Here is her story of that day, lightly edited and as told to FLYING.

I guess, like any exercise I've trained for, it all started kind of the day prior. We had a brief for all the crews, we had a bigger picture operation brief, and then the C-17-specific brief for the crews executing, and then everyone was sent to crew rest, just like every other exercise that we've trained for.

It didn't really hit me until after it was all over, the significance of that day and of that flight.

I was a part of the 816th [Expeditionary Airlift Squadron] for the entirety of the evacuation. We'd been working long hours, getting very little sleep. Crews were, you know, putting the pedal to the metal, throttles to the max for going on two weeks to two and a half weeks, almost three weeks. Everyone was exhausted and it was kind of that culminating event that day.

I think the most significant thing that I remember of that [last] flight was just looking in the back of our aircraft. We were taking some of the troops that were at the Abbey Gate, which was the gate that had been bombed earlier during the operation. They were in the back of our airplane, and no sooner than five minutes off the ground, they were asleep. You could just see the exhaustion, the wide array of emotions from everyone on board from what everyone had been through over the past couple weeks. That was pretty eye-opening. It was a relief. It was relief, sadness, anger, frustration. Everything.

I will tell you that, on that day…when the airfield was overrun, I was at Al Udeid [Air Base] monitoring, and I have to say that that was probably one of the scariest moments I've ever had in my career. Just kind of watching it happen real time and not really being able to do anything about it. I had the squadron commander in the room with me, and that's the most scared I've ever been, pretty much all of us. We immediately were trying to get a hold of anyone on the ground there, to try and help to see what we could do, what we could—anything. And for the rest of that whole time, and especially on that last day, it was a concern of all of ours.

“It didn't really hit me until after it was all over, the significance of that day and of that flight.”

We were always on the lookout for anything to happen. Anything and everything could have happened that day, and we were eternally grateful that things turned out the way they did on that final day.

We had full trust in our crews. Our crews have trained for these moments their whole careers. Every single one of them brought their A-game. Every single one of them was ready, was able, had the knowledge, had the skills, and were willing to think on their feet. Those crews on that first day, when they did get overrun, every single one of them made safe judgment calls, made the right judgment calls, and did what was necessary to keep their crews, their aircraft, and everyone safe.

Back in the beginning planning stages of the operation, we had initially thought that we could [execute] an orderly evacuation of putting people in seats on the airplane, and try—especially with the coronavirus concerns—facing everyone out. But in the first days when [the NEO] first started, that just wasn't feasible. Some of the judgment calls were using past experiences and the knowledge that crews have, being able to do the floor-loading process. So just bringing people on and having them sit on the floor, essentially, with straps. And it wasn't until, you know, later down the line, that the approvals and things caught up with that.

“Do you have a military flight story to tell? E-mail us at editorial@flying.media.”

Even now, we really don't have a good number of…how many people you could fit in the cargo compartment. A few years ago, with the Philippine evacuation, we had 600-something. On that first day [during the Afghanistan evacuation] when one of the jets was overrun, and they departed, I think their number was in the 800s. There's really not a good number that we have even now. So every single day, those crews…we would give them our best educated guess and different planning numbers to go off of, but every day they were making that judgment call of how many they were willing to accept on every flight, to make sure everyone got safely out.

My main job was actually to be on the ground at Al Udeid [Air Base] prepping the crews as they were stepping out to go and fly. There were crews that went in and out five, six, seven times. I would estimate that they were bringing out thousands across their mission.

The NEO in particular—we actually don't have very much training [on that]. There's been a couple of weapons school papers written about it, about how we would be employed in a NEO. Honestly, in the planning for this NEO, that's mostly what I relied on—overarching Air Force and DOD regulations of evacuations, and then our specific weapons school papers about a NEO and how the C-17 can be employed in that.

Going to do an evacuation is just like any other mission.…Unfortunately, Kabul was kind of a thunderstorm of the worst case in every planning scenario. So there was a lot that each crew member had to deal with on all of those missions.

Because Kabul is at a high elevation [with a] high pressure altitude, and it also has significant terrain, we did actually use tactical arrivals and departures going in and out of that airfield. Because of that terrain, it has had a really high climb gradient [on departure], which on a normal given day, on a normal mission going out of Kabul, it really limited the amount of weight that you could take off with. [During planning] we had come up…with different routes to try and mitigate that, to help crews be able to take off at a heavier weight and have a lower climb gradient to get out of Kabul. That was something we looked at beforehand to help crews with their decisions and being able to accept more weight.

Every airfield, there's the obstacle climb gradient that TERPS [terminal instrument procedures] uses to plan any [IFR] departure leaving an airfield. The rule of thumb is the 200-feet-per nautical-mile rule. That's like the slope that they use. And then, if there are any obstacles that break that slope, then they have to raise it up and create a new climb gradient. So for Kabul, I believe at least on the primary departure runway, the climb gradient was 400 feet per nautical mile, which for the C-17, decreases our performance. If we want to be able to climb out at that climb gradient, we would have to decrease our weight either via fuel or cargo in order to meet that climb gradient off of that runway.

You want to land on [Kabul Airport's Runway] 29 and then also depart on 29 because that gets more aircraft in and out. Otherwise, if you depart the opposite direction, you'd be conflicting with anyone trying to come in and land. Being able to take off and land in that same direction was ideal. We planned a VFR departure, which takes away the IMC TERPS requirements for the climb gradients, and we were able to come up with a VFR climb gradient to ensure obstacle clearance using a VFR ground track. Essentially, they had to be able to see the obstacles in order to take off and maneuver around them. In essence, it took the onus of obstacle clearance off of the TERPS planners that designed the departure procedures and put the onus on the pilots to see and avoid, essentially, the terrain to be able to depart.

I still think about it a lot. I will be completely transparent and say that it took me a really long time to kind of get back to normal after that whole experience.

It took me a few weeks just to, kind of, get back to normal life. It was an experience and I don't think I'll be how I was before, probably ever. It's definitely something that's going to stick with me forever. It changed a lot about how I look at my career, what I want to do with my career. It reminded me why I went to the Weapons School for C-17s. It reminded me why I wanted to go, why I wanted to go through that training. It also reminded me about our [cargo] community. Our community is, a lot of times, overlooked. We're not in the spotlight a lot. We're always behind the scenes; we're not fighter pilots, we're not the tip of the spear in most instances.

It was a good reminder of the importance of what we all do.

I think the biggest thing that I want to make sure that people see is just the heart and the willingness of this community and the airmen, not just in the C-17s. Airmen on the ground, in maintenance and support functions—they were all doing everything they possibly could to get the mission done, in spite or despite of anything that was going on at higher levels. They were willing to fight. And that's something that people need to know.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox