The controller would ask periodically if we were under the clouds yet, and he finally said, “Well, I hope you get there soon—you’re holding up all the traffic at San Antonio International and Kelly Field.”

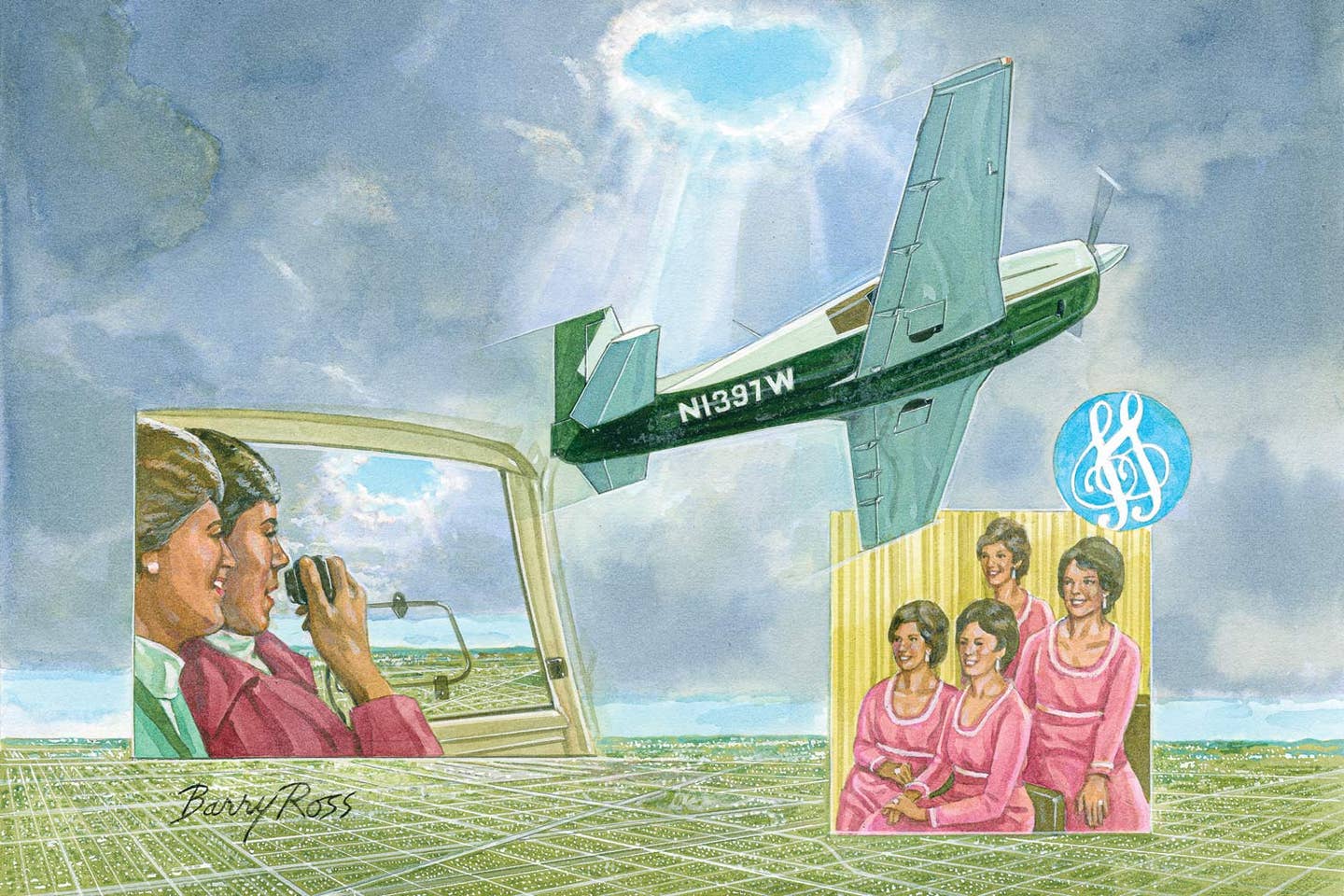

It was a beautiful March day in 1976 in South Texas, and I was excited to be flying my Sweet Adeline women’s barbershop quartet from San Antonio to Amarillo, Texas, for our regional barbershop singing contest. My husband and I owned a 1965 Mooney M20C—yes, with a Johnson bar—and we flew it quite a bit just for pleasure, always alternating as pilot in command. I was really happy that Julie, Carole and Kathy trusted me enough to fly with me. After all, at that time, a woman pilot was a member of a rare breed.

With Carole in the front seat and Julie and Kathy in the back, we departed San Antonio International on a 270-degree vector. There was an overcast layer at about 2000 feet agl, and being a VFR pilot, I was flying under it when I saw a big hole in the clouds over to my left, in the vicinity of Kelly Air Force Base (now officially Kelly Field), which was an active military airport at that time. The cumulus layer didn’t look very thick, so I asked for and was given permission to divert to the southwest and ascend through the hole.

I reached the large hole in the clouds and started spiraling upward, thinking: “This is great. Just a few more minutes, and we’ll be on top and on our way to the contest.” However, as I continued to climb, the hole was getting smaller and smaller until it disappeared altogether, and I found myself in the clouds. Having experienced loss of spatial orientation when my instructor put me through recovery from unusual attitudes, as well as having spun in the vertigo chair at a flight-safety meeting, I was well-aware that I was susceptible to losing spatial awareness. That really scared me. So I established a very shallow bank and kept my eyes riveted to the instruments, making sure that I didn’t increase my bank as I continued to spiral upward through the overcast. I tried to keep a confident bearing and act like this was an everyday occurrence for me so I wouldn’t make my passengers any more uncomfortable than they naturally were, not being able to see anything outside. But, truthfully, I was petrified. Of course, I didn’t report being in IMC.

The controller would ask me, periodically, if I was on top yet, and I would give him a negative response.

Then a new masculine voice came over the radio, saying, “You girls sing pretty up there in Amarillo.” I was stunned. Who could that possibly be, knowing who we were and where we were going?

Kathy, in the back seat, asked in an awe-stricken voice, “Was that God?” I couldn’t imagine who it was, but we found out later that it was the husband of one of our chorus members, who was a test pilot.

I kept on climbing, until finally someone broke in with a pilot’s report: “To the lady trying to get on top, be advised that the tops are at 16-5.”

Clearly, this dictated that I abort my plan and return to a lower altitude under the overcast, so I told the controller we were coming back down. “Back to the airport?” he asked hopefully. “Negative,” I said. “Just back down under the clouds.” I changed to a descending spiral, still being very careful to watch the instruments and keep my bank very shallow.

It’s difficult to keep an outward show of confidence when you are pretty scared of the situation you are in, but I think I managed pretty well. Carole said she looked back and saw Kathy as white as a sheet. She didn’t say that I was, so I guess I faked it pretty well. Julie told me later that she didn’t know we were spiraling upward and trying to get above the clouds—she just thought we were flying. She said she was a little uncomfortable not being able to see outside but had complete confidence in me.

Read More: I Learned About Flying From That

The controller would ask now, periodically, if we were under the clouds yet, and he finally said, “Well, I hope you get there soon—you’re holding up all the traffic at San Antonio International and Kelly Field.” Gulp.

Eventually, I reported that we were under the clouds, and the controller, sounding very relieved, vectored me towards the northwest. At that point, I decided to check the weather once more, and the Amarillo forecast for our ETA had been updated: 12 degrees Fahrenheit with winds at 35 knots gusting to 45, at a 35-degree crosswind to the active runway. That was the last straw for that ill-fated flight. We returned to the airport and—yes, you could do this back then—bought tickets and boarded a commercial flight for Amarillo.

I felt bad about causing such a disruption, but then I told myself that the controller should have never given me permission to go up through a hole in the clouds in the first place. Maybe he didn’t know about sucker holes. I know I didn’t.

But in my defense (and that of my instructor), I learned to fly in a tiny oil town in West Texas, west of Lubbock and near the New Mexico line. We didn’t normally have clouds down low that could form in layers with holes to tempt the unsuspecting pilot.

An oil company had blessed our little town with an airport, and we had two paved runways: 09/27 and 03/21/22. (The southwest runway had a 10-degree dogleg near the end and a pump jack close beside it.) Runway 27 was the most challenging. The homeowner just across the street from the approach end had installed a 300-foot TV tower over his house “so airplanes wouldn’t hit his roof.” So you had to clear that and then slip down to the runway. The wind was always blowing from south of due west, so you were dealing with that crosswind while slipping. A few seconds later, the huge school-bus barn blocked the wind, so you had to correct your crosswind configuration. And then, suddenly, you were past the barn, so still another adjustment. Woe to the unsuspecting pilot landing there for the first time.

We built hangars out of scavenged pipe and corrugated steel. Our personally owned 1,000-gallon barrel held avgas purchased at 19 cents a gallon. Rent on the Cessna 150 was $12 an hour, and our instructor charged $8 an hour. The local banker financed our planes with the same type of loan he made to the local farmers: pay only the interest. That’s how a couple of teachers could afford to fly in 1969 and ’70.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox