When we took off in the rental Cessna 140, neither of us had any idea that before the flight was over, I would inadvertently become a "test pilot." A test pilot is the first person to fly an airplane design that has never been flown by anyone else. Change the shape of any flight surface and it is a new, untested design the first time it is flown.

My flight as a "test pilot" began 30 minutes into a training flight. My student was a private pilot who had scheduled me to help him become more comfortable and competent in a Cessna 140, the type airplane he planned to purchase. After he had demonstrated a series of stalls, slow flight and steep turns, I suggested we return to the airport and work on his takeoffs and landings. He had just given the flight controls to me, requesting that I make a steep right turn so he could take a photo of the snow-covered land below. About 10 seconds into the turn, we felt and heard a loud thump that prompted me to gently roll back to a wings level position.

My first thought was, "Bird strike!" and I said the same to my student. As the reality of our situation set in, I gently tested right aileron, left aileron and back to wings level when I realized I was holding almost full right rudder. In my mind, I instantly replayed the loud thump, wondering how bad the vertical stabilizer or rudder was damaged. "How big of a bird did we hit? Was it a bird or maybe another aircraft from behind us?" I remember a split-second or maybe several seconds early on when I was really scared and thought, "This is it!" When our aircraft didn't begin tumbling from the sky out of control, I was able to compartmentalize my fears and turn my entire focus to flying the airplane. It was natural for me to focus on flying the airplane first and foremost.

I decided to make only the changes to power or flight controls that were absolutely necessary to allow me to return to our home airport. And during any changes, I would do nothing abruptly while remaining alert for any additional abnormal inputs. I advised my student I was going to reduce power and airspeed in order to lower the stress of the airflow on the damaged area. Next, I entered what was probably a standard rate turn to the right as I headed toward our home airport, 10 miles distant.

With the aircraft on the northwest heading and stabilized with wings level at 2,500 feet msl, the need for extreme right rudder remained unchanged. I called our home airport to report eight miles southeast for a straight-in to Runway 30. There was nothing else to do but continue flying the plane, alert for any changes ... and share some thoughts of reassurance with my student.

I remember advising the student about what must have happened, what I was doing and that we were doing okay. I told him about a similar situation several months earlier when I was working with another student in his Luscombe 8E and we had a bird strike and later landed safely to find only minor damage. My ploy to relax my current student appeared to work. I then invited him to get on the controls very lightly so he could feel what was happening. After all, he was in the same situation and deserved to know what I had learned so far. He too was surprised at how much right rudder I was holding. I asked him to get off the controls, as I reassured him we were doing okay, had control of the airplane and that the landing should not be a problem. I believe I remember him saying something about not minding us practicing takeoffs and landings some other time!

Listening for air traffic at my home airport, I called again to report our position at four miles southeast for a straight-in for Runway 30. I remember thinking that as long as we don't hear or see any other air traffic in the pattern, there was no need to declare an emergency.

I continued my approach, reporting in at two miles "on final for Runway 30" and again at one mile. By the time we were on a one-mile final, I had reduced power to 1500 rpm and airspeed to 80 mph, with no significant change in the required rudder pressure. We were on short final, then over the threshold as I continued reducing power to idle at about six inches above the runway. As I held the airplane approximately six inches above the runway to continue bleeding off speed, I felt my right foot moving further toward the firewall in order to keep the nose straight down the centerline. I remember running out of rudder just as all three wheels touched down. With full back-elevator to keep the steerable tailwheel "nailed" to the surface, I quickly regained normal rudder authority as the speed slowed and we tracked straight down the runway center. Thank you, Lord!

I advised my student that we would continue taxiing back to the hangar and shutdown there, instead of stopping on the taxiway to find out what happened. I had a strong feeling that whatever damage there was, this airplane wasn't going to fly any more that day.

Back on the ramp in front of the hangar, I did a U-turn (enjoying the regained rudder control) and shut down the engine. A small crowd was already gathering, including some who had been preparing to start their engine, others who followed us from their hangars located along the taxiway. As we exited the airplane, a fellow aviator friend jokingly asked whether I noticed a difference in the flight controls on landing, compared to takeoff. I smiled and turned toward the tail section, expecting to see a damaged vertical and maybe even a bent rudder. Surprise! There was no damage! My brain had difficulty grasping the reality that the tail section was not damaged; after all, I had held extreme right rudder and actually would have liked more rudder travel during the landing.

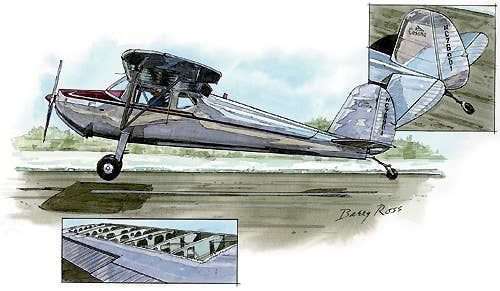

Taking a step or two toward the tail to verify what my eyes saw but my brain was challenging, I then turned toward the front of the airplane. I was totally amazed, possibly a bit shocked, when I saw that most of the fabric from the top surface of the port wing missing! The majority of both wing spars and nine ribs were clearly visible. A three-by-eight-feet panel of fabric had ripped off during the steep right turn. My reaction was a simple, Oh my God, thank you so much!

While trying to absorb the reality of the damaged wing and the fact I had actually been able to control and land the airplane under those conditions, I remember lots of "Congratulations" and other words of praise from fellow pilots. Then the student said what I had been thinking, "To still be flyable with that much of the wing surface missing just confirms how safe the Cessna 120s and 140s really are." He added that it reassures him that this is the type airplane he wants to purchase as soon as he finishes getting checked out in it.

Later when the adrenalin wore off and I was able to reflect on everything that had happened, I realized there were some valuable lessons learned that are worth sharing with other pilots. First, the key element that made our approach and landing uneventful was the technique that I teach and practice in both tailwheel and nosewheel aircraft. Basically, it's a normal approach in which the pilot flies the airplane (power reduced to idle, with or without flaps) to within six inches of the runway and then continues flying it as long as possible, except in high winds and gusts when it's best to fly gently onto the runway. Providing the pilot is properly controlling the aircraft's drift and yaw, this technique results in consistently easier, smoother and safer landings.

There is an alternative landing technique I've seen some pilots use and it really scares me. They focus on beginning a flare 50-100 feet above the runway, hoping to arrive at landing/stall speed as they touch down -- had I used their method, I would have run out of right rudder much higher than six inches above the runway. Although I refer to my technique as "the tailwheel landing," it is the landing technique I have always taught and practiced in any type airplane. It even works great on introductory flights.

Lessons Learned (and Reaffirmed):Aviate -- When an emergency happens, always fly the airplane first, foremost and never stop flying it! An important part of flying the airplane in our situation was to continually evaluate the situation, make only gentle, minor changes as necessary and remain constantly alert for any changes in aircraft performance.

Navigate -- At all times, it is important to know where you are. When practicing slow flight, stalls and other maneuvers, it is easy to loose track of where you are. Precious minutes spent looking for the airport could change the outcome of a challenging situation. I had been giving the student headings to keep us in a known practice area, which made an immediate turn toward our airport possible without a GPS or other navigation aids.

Communicate -- Although I contacted my home airport immediately to report 8 miles SE and inbound for Runway 30, I did not declare our situation to anyone on the ground. I didn't squawk 7700 or declare an emergency. I thought, "Why create a lot of attention when I have everything under control … nothing else is going to happen to me (us) … ." Later, I realized just how wrong I was for not declaring an emergency, and how fortunate we were. If our situation had deteriorated further, resulting in an off-airport landing or worse, who knows when any emergency rescue efforts would have been activated?

Preflight -- When I climbed up to dip the tanks during preflight, I noticed that the two 3-inch sections of loose tape near the left wing's top leading edge fabric were no worse than the last several times I'd flown the airplane, so I didn't consider it significant at the time. After all, other pilots and flight instructors must have seen it also. In the future, I will advise any students and other pilots that any missing surface covering screws or loose fabric are sufficient reason to ground the aircraft until corrected.

Great Design -- Cessna 120s and 140s truly are great little airplanes that can sustain lots of damage and continue flying; however, this test pilot strongly recommends sticking with factory approved aircraft with all of their parts properly attached.

The cause of the fabric failure is being investigated.

To see more of Barry Ross' aviation art, go to barryrossart.com.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox