A Glimpse Into ‘The Good Life’ Provides Reflection

An opportunity to test out a gleaming new aircraft gives this pilot some surprising thoughts.

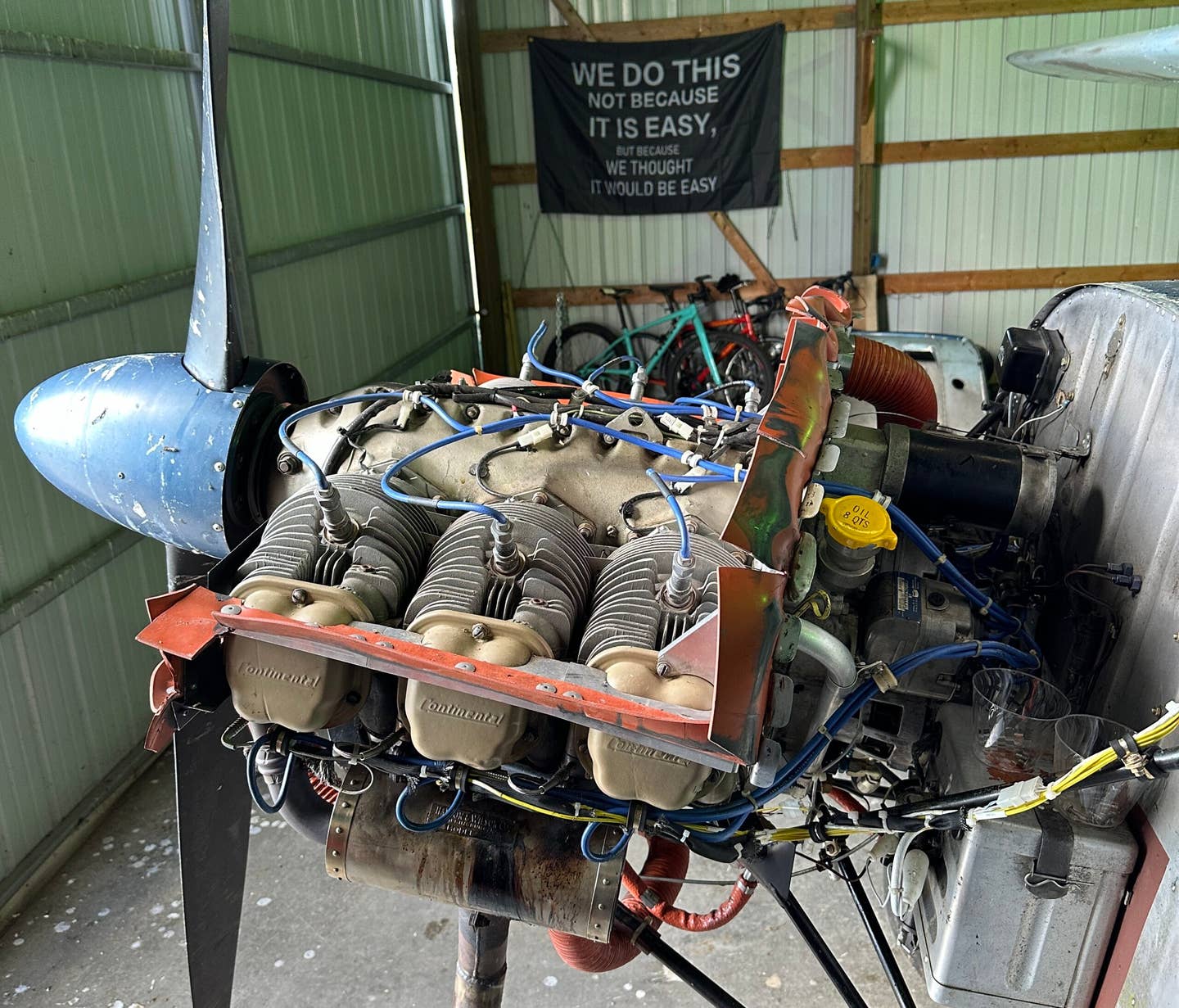

The opportunity to fly a factory-new aircraft may spoil owners of more humble aircraft in some ways, but also may introduce a new appreciation for the benefits of each. [Photo: Jason McDowell]

Spend enough time chatting up airplane owners at your local FBO, and it doesn’t take long to realize how widely the ownership experience can vary from one person to another, even among common single-engine piston aircraft types. This really hit home for me last summer at EAA AirVenture 2021.

I had just purchased a bratwurst and was looking for a place to sit down. Spotting an open seat at an occupied picnic table, I asked the folks sitting there if I might join them, and as is always the case at Oshkosh, I was welcomed with smiles all around.

The usual, friendly introductory questions made their way around the table, and I came to learn that the three gentlemen had all flown in from Arkansas—two in a Cirrus SR22 and the other in a 2015 Mooney Ovation. It didn’t take long for them to continue their original conversation centered on the ongoing maintenance and operating expenses for their airplanes, and as a first-time owner myself, I listened with interest.

“We may have all been flying single-engine piston airplanes, and we may have been flying them to similar destinations, but when it came to the ownership experience, we were clearly living on completely different planets.”

The Mooney owner was lamenting a recent annual inspection that had turned out to be far more expensive than anticipated, amounting to about $9,000. His maintenance shop had, as it turned out, discovered around 50 discrepancies ranging from worn brakes to a more serious engine issue. He wasn’t whining and wasn’t expressing any regret—he was simply explaining his ownership experience in a resigned, matter-of-fact manner. It was a complex airplane with all-weather IFR capability, he reasoned, and unexpectedly pricey annuals were simply the price of admission.

The Cirrus owner had similar reflections. His seven-figure airplane was new enough that most of his maintenance concerns were still covered under warranty, but he planned to own it for many years and was fully expecting to face similarly high maintenance expenses in the future. The parachute alone, he explained, has to be repacked every 10 years to the tune of about $18,000.

I paused, staring at my now half-eaten brat and considered these numbers. The parachute itself cost $150/month to own and maintain. That’s more than I was paying for hangar rent. The aforementioned $9,000 annual amounted to about a third of the acquisition price of many of the airplanes for which I’d been shopping over the past couple of years.

We may have all been flying single-engine piston airplanes, and we may have been flying them to similar destinations, but when it came to the ownership experience, we were clearly living on completely different planets.

As I stumbled back into my far more humble world of ownership, I’d reflect upon this reality regularly, wondering what it must be like to fly an airplane that was more than 60 years newer and an order of magnitude more expensive to own and maintain than my trusty old Cessna 170.

As it turned out, I would only have to wait a few months to find out. Through a connection separate from FLYING, I was invited to take a demo flight in a brand-new Beechcraft Bonanza G36 at the Textron headquarters in Wichita, Kansas.

Newness Unveils Another World

I’d flown an old, 1960s-era Bonanza before, and as the general, overall design of the Bonanza hadn’t appreciably changed since its introduction, I wasn’t expecting a vastly different experience. And while the performance numbers and handling did indeed feel very similar to what I’d remembered, I didn’t anticipate how the small details and refinement would all add up to completely change the overall experience.

Up until that demo flight, all of my flying had taken place in well-used, but well-loved airplanes. Everywhere you looked in these modest mounts, various levels of wear were evident—door jambs were scratched up, interior trim was cracked, paint was faded, ashtrays were stuck open, and so on. Similarly, everything you touched reminded you of the decades of use incurred by the airplane. Seat tracks required some jostling to click into place, door handles needed some muscle to operate, and one look at the upholstery reminded you of the multiple generations that had flown the airplane over the years.

The result was a constant reminder that—while perfectly airworthy—these were tired airplanes. Consciously or subconsciously, you’d never stop scrutinizing each mechanical component with a bit of skepticism, confident in your preflight inspection but never forgetting that you were only ever one part failure away from having to consult an emergency checklist.

Sliding into the new Bonanza was like sliding into another world. Unlike all the previous airplanes I’d flown, every touchpoint reinforced the feeling of flawless mechanical perfection. The solid metal toggle switches clicked into place with satisfying precision and an audible clack. The doors opened and closed smoothly and easily. The carpet and headliner fabric was perfectly trimmed and fitted, the new windows provided flawless outward vision, and there was a total lack of squeaks and creaks as we taxied over any broken, uneven pavement.

In the air, the airplane flew as I’d expected, with no big surprises—predictably pleasant, with stable, responsive handling. But the aforementioned fit and finish exuded a feeling of precision I’d never felt before. I was enveloped in a sense of security and peace of mind, and I came to realize that this aspect—despite not being quantifiable or showing up on a spreadsheet—was much of what those well-to-do owners were paying for when they bought their new aircraft.

Additionally, I considered how this impression would be particularly noticeable by non-pilot passengers. Those not familiar with the meticulous nature of regular aircraft maintenance might be disproportionately put off by an older airplane that is mechanically sound but visually and tactilely shabby. They would certainly be much more at ease in an example with exquisite fit and finish and a quieter cabin.

I came away from the demo flight with a new appreciation for factory-new aircraft. With a price tag that starts out at nearly $1 million, I was no closer to being able to afford the Bonanza, but I had a much better understanding of the value they provide to pilots fortunate enough to own them. Without an aging airframe and components constantly lurking in the back of their minds, those owners could enjoy piece of mind while focusing their attention on the flight itself.

How Did This Change Me?

On the airline flight home, I wondered whether the factory-new experience might have spoiled me, and whether I’d become less enamored by my humble 170 that looked as though it had served in multiple wars. Fortunately, my fondness for it remained.

Although I had a new respect for the gleaming new machines, flying one also gave me a new appreciation for the experience of owning a vintage example…and indeed, for being an owner at all.

Just as the factory-new benefits of confidence and peace of mind are difficult to quantify on a spreadsheet, so too is the satisfaction of serving as a caretaker of a vintage airplane. Becoming intimately familiar with the condition and age of each system and providing the necessary care to ensure the airplane is passed on to the next owner in as good or better condition as when I acquired it is immensely rewarding. It’s a hobby in and of itself, and provided you go into ownership with properly calibrated expectations, it’s a darned enjoyable one.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox