The Arduous Task of Getting an Airplane Home

Good friends, a good plan, and a little bit of danger gets the author’s new pride and joy home just in time for Oshkosh.

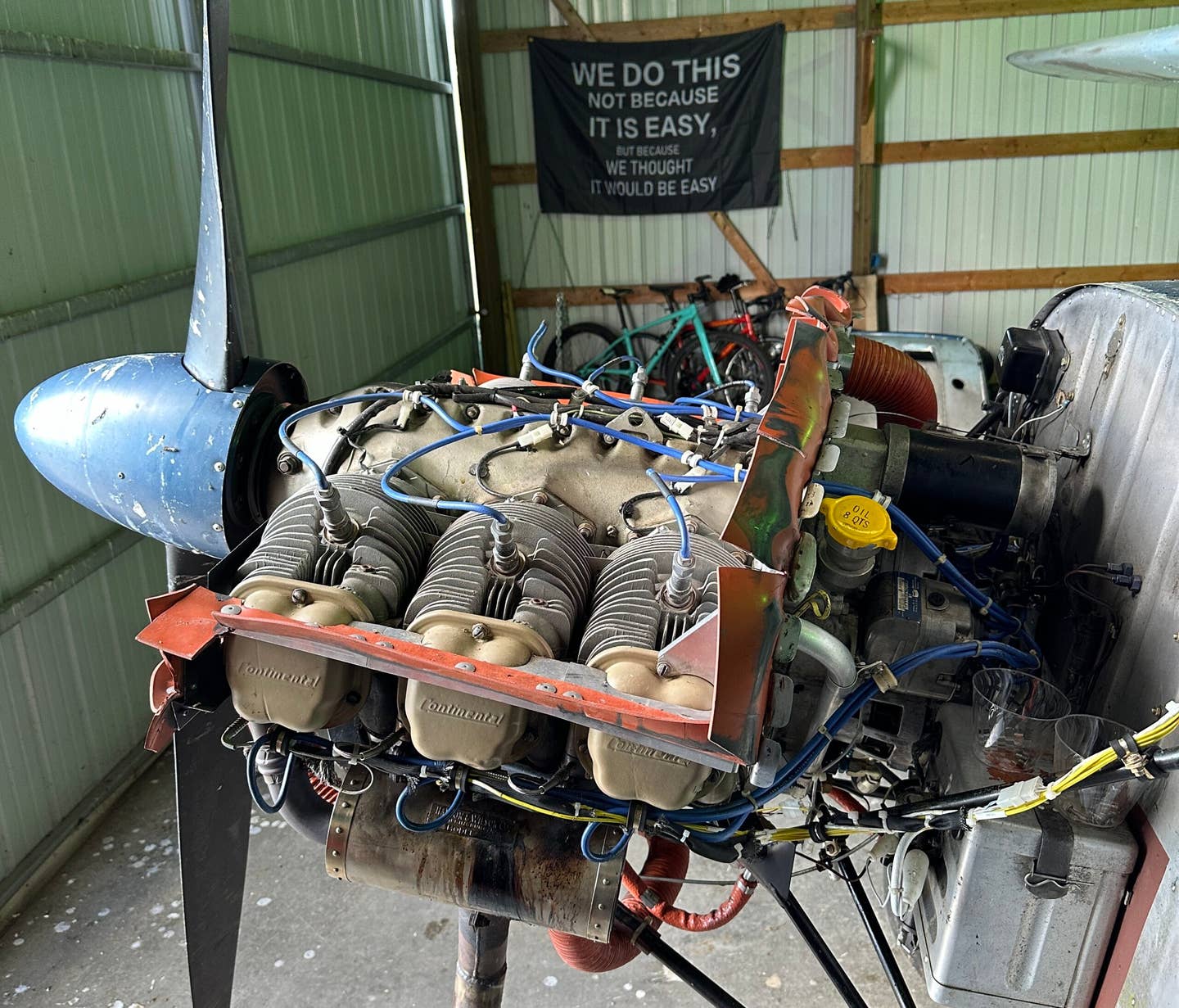

Good friends come through to ferry the author’s newly-purchased 170 from Seattle to Wisconsin. [Photo: Marty Coaker]

When arranging for good friends to ferry your newly purchased, 68-year-old airplane clear across the continent for you, it’s common courtesy to make their task as easy as possible. Pay for their meals. Spring for nice hotels. And try to avoid placing them over the Rocky Mountains in air filled with forest fire smoke during a large-scale GPS outage.

In my efforts to be a good friend, I managed to achieve the first two items, but fell woefully short on the last one.

It all started back in July 2021. I had successfully located and purchased my dream airplane, a 1953 Cessna 170B, from a gentleman near Seattle who had owned it for more than four decades. The entire purchasing process went eerily well. The prepurchase inspection revealed no serious issues. The airplane flew beautifully. And the seller was a wonderful individual who provided me with all the time I needed and happily held the airplane for me without a deposit.

The most challenging aspect of the purchase was getting the airplane from the Seattle area to the area I call home near Madison, Wisconsin. This is a distance of more than 1,400 nm, not taking into account the necessarily circuitous route through various mountain passes. It would be a relatively challenging trip for any pilot.

For me, however, it was an endeavor well beyond my capabilities. Although I had recently gotten current and earned my tailwheel endorsement, I hadn’t flown regularly in about 18 years and had yet to truly get back into the swing of things. My tailwheel experience, such as it was, would be laughable in the harsh crosswinds of the western plains. And having spent my entire life in the Great Lakes, my familiarity with mountainous terrain was based upon ski trips to former landfills. To attempt the trip on my own would be foolhardy at best.

I briefly considered hiring an instructor to make the trip with me, turning it into an educational cross-country adventure. But as I only had stretches of three days off from work, the ensuing rush to make it home in time would have welcomed cut corners and severe bouts of “get-home-itis.”

With the airplane paid for and still hangared on the other side of the continent, I did some brainstorming. Yes, I had some pilot friends in the Seattle area, but no, none were available to make a ferry flight. Yes, some dedicated professional ferry pilots were interested, but no, not anytime soon.

A Friend With an Idea

I soon found myself lamenting my situation to my good friend from college, Marty. He spent much of his career flying for the airlines before succumbing to boredom and making a jump to aerial firefighting. He’s now part of the flight crew that flies four-engine tankers in support of wildland firefighters. He tells tales of his newfound purposeful flying that’s always challenging, fills the soul, and leaves no doubt why he left his original career. He often expresses pride in being a small part of a massive team with a common goal, and how gratifying it is to play his part. It’s safe to say he’s thankful and no longer bored.

Marty is also a great friend, always happy to lend an ear and listen to my whining. But this time, as I described my airplane predicament, he took a particularly close interest. “Where did you say it’s hangared right now?” he asked. “Arlington, Washington,” I replied. He became quiet for a moment and then excused himself to make a phone call, saying only that he had an idea.

When we spoke again later that day, I learned that good fortune was continuing to smile upon me. As it happened, Marty was slated to attend recurrent training with his coworker and our mutual friend, Jared. This training would be taking place in Abbotsford, British Columbia, in a matter of weeks, and they would be passing within a mile or two of my airplane on their way home.

Rather than subject themselves to the misery of several hours of airline travel, Marty suggested, why not instead subject themselves to several days of general aviation travel? He would be trying to get home to Michigan, anyway, and bringing my airplane to Wisconsin would get him most of the way home.

Jared thought the trip sounded fun. As the owner of a 170 of his own with a serial number only 45 away from my own, he was quite familiar with the airplane and how it flew at higher elevations. He also lives in Spokane and has plenty of mountain flying experience. Marty couldn’t ask for a better companion.

Best of all, barring any unforeseen weather or mechanical issues, I’d have my airplane just days before EAA Airventure 2021 kicked off in nearby Oshkosh…which meant I’d theoretically be able to fulfill a lifelong goal of camping beneath my own wings at the show. I concurred that it was a fantastic plan, and promised to cover any and all expenses incurred along the way.

I put my two friends into contact with the seller, and they met up as planned a couple of weeks later. After loading their gear, a few boxes of parts, and logs for the airplane, they carefully completed a weight and balance and set off. The seller, ever the gentleman, insisted on paying to top off the tanks and then watched as his pride and joy of 41 years departed the pattern for the last time.

The Long Trip

Jared earned his keep on day one, helping to thread their way through the Cascade mountain range via Snoqualmie Pass. A couple hours later, they arrived at his hometown of Spokane for the first overnight. It was a relatively uneventful day, save for a considerable amount of smoke in the atmosphere from all the forest fires peppering the region.

Day two was a big one. Anticipating a very long day, the lads got an early start and were welcomed into a horribly smoky atmosphere. Although the visibility was limited, conditions were still VFR and they nursed the heavily laden 170 up to 10,500 feet to clear the terrain ahead. After leveling off, they were able to see the highest mountaintops poking out from the layers of smoke below. The mountaintops served as a visual confirmation of their route and position, which was fortunate shortly thereafter when, one by one, the various GPS units aboard the aircraft stopped displaying position data.

At first, they suspected this was an isolated problem with the in-panel GPS/COM unit. But further investigation revealed a corresponding lack of data coming from the iPad, both phones, and even the Garmin inReach satellite communicator. It was, they realized, a complete systemwide outage—and they were left with good old-fashioned pilotage and dead reckoning to get them the rest of the way through the smoke and over the Rockies.

Were my aircraft under the command of just about any other pilots, I’d have been alarmed. But these were professional aerial firefighters who spent more time in the smoke than many of us do in the air. Both had considerable experience competing in precision traditional navigation under the National Intercollegiate Flying Association. I couldn’t possibly have chosen a more perfect crew for the situation.

Sure enough, they reverted back to basic navigation techniques with ease. At one point, Jared informed Marty that, by his calculations, they should be over a certain airfield in a matter of seconds. Marty initially had trouble locating the airfield only because it was directly beneath them, and could be seen only by pressing a forehead against the side window.

By the time they reached Great Falls, Montana, the smoke had dissipated and the GPS navigation had come back to life. They spent the remainder of the day cranking out three-hour-long legs, and by the time they landed in Minneapolis, they had logged 11.2 hours of flight time. Jared hopped an airline flight home to Spokane, Marty grabbed a hotel room, and I can only assume they both enjoyed some truly blissful sleep that night.

The third and final day, Marty began the last segment of the trip solo in perfect, sunny weather. He was welcomed back into the Midwest with scenes of lush, rolling greenery punctuated by lakes and rivers—a notable departure from the previous backdrops of hazy dirt and rock. After topping the tanks off in Middleton, Wisconsin, he arrived at my home airfield south of Madison, a privately owned grass strip about 2,500 feet in length.

When I arrived, Marty had just parked the airplane and was unloading his bags. There, a bear hug and a ceremonial passing of the keys marked the official delivery of my first airplane. We quickly parked it in the hangar and hopped in the car so I could get him to his airline flight home. The 16.7 hours of flying across the country had taken its toll, and his satisfaction of safely delivering my airplane was matched only by his anticipation of some relaxing days off.

It was a day worthy of reflection. After years of saving and many months of effort, my very own airplane was safely buttoned up at my home airport. Oshkosh was only days away. Although I wasn’t yet checked out or proficient in the airplane, there might yet be a way to get it up to the show and camp beneath my own wing.

All of these thoughts whirled around my head for the remainder of the day and into the night. Thoroughly distracted, routine tasks like household chores and meals fell to the wayside. But no moment was as surreal as when, with annoyance, I wondered out loud, “What the hell is this in my pocket?” and realized it was the keys to my own airplane.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox