Smaller, Lighter Cessna 327 ‘Mini Skymaster’

The 327 was Cessna’s solution to a downsizing opportunity. Then it ended up in a NASA wind tunnel.

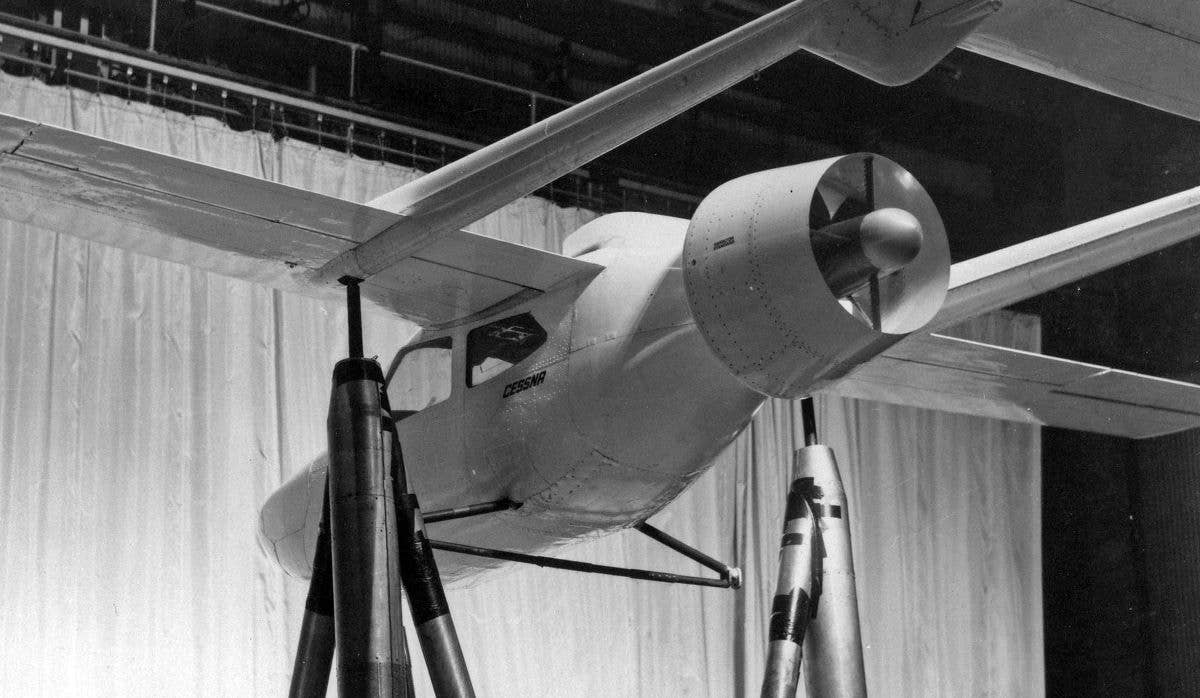

A close-up shot of the 327 undergoing testing in NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. [Credit: NASA]

Once upon a time, GA aircraft manufacturers pursued market niches with the ferocity of wild dingos. When marketing teams identified a potentially underserved customer segment, they wasted no time introducing minor variations to existing models to accommodate it. Compared to today’s offerings, the resulting variety of aircraft was spectacularly broad and varied.

When Cessna determined some customers would be willing to pay a bit more for a slightly more powerful 172, for example, the company introduced the 175 Skylark. This was little more than a 172 with a different engine, but the company was in pursuit of new market segments and opted to advertise it as an entirely different model.

Similarly, Beechcraft identified markets for both full-sized and smaller light twins in the forms of the Baron and Travel Air. With four seats instead of five or six, thriftier 4-cylinder engines, and significantly lighter weight, the Travel Air was presented as a simpler, more compact solution that emphasized economy rather than outright performance.

Fresh off the successful launch of the unique, twin-boom Skymaster, Cessna began exploring the same opportunity in 1965. Recognizing the market might have room for a smaller, lighter version of the Skymaster, it built a single prototype of the Cessna 327. While it was never given an official name, various sources use the nicknames “Baby Skymaster” and “Mini Skymaster.”

The rationale behind this model was likely rooted in findings shared by other manufacturers—that many owners and operators of twin-engine aircraft travel alone or with only one passenger most of the time. For these customers, it made little sense to haul around excess seats and cabin space while burning additional fuel and paying more to maintain larger, 6-cylinder engines. The diminutive Wing Derringer was an extreme example of minimalist light twins.

The 327 was Cessna’s solution to this downsizing opportunity. Essentially a 172-sized Skymaster, it was both smaller and lighter than the larger centerline twin. Equipped with two 4-cylinder, 160 hp IO-320 engines, it utilized Cessna’s strutless, cantilever wing, and raked windscreen, similar in design to the 177 Cardinal series.

The smaller size and sleek lines gave the 327 a sporty look compared with the more utilitarian Skymaster. But like the Skymaster, the front seats were positioned well ahead of the wing's leading edge. Combined with the lack of wing struts, this would have provided outstanding outward visibility and positioned the 327 to be a favorite for aerial photography.

Cessna never published any dimensions or performance specifications for the 327. Using comparable light twins with the same engines as a reference, we can predict the 327 likely would have had a maximum takeoff weight of 3,500-4,000 pounds, with a maximum cruise speed of 150-175 mph. Fuel burn would also have been correspondingly lower, roughly on par with a Piper Twin Comanche with similar engines.

First flight took place in December 1967, and Cessna flew the 327 until the following year, logging just less than 40 hours of test flights. At that time, the airplane was presumably placed into storage, and the registration—N3769C—was canceled in February 1972. But unlike many other prototypes, the 327 would serve one last purpose before vanishing forever.

The airplane’s final role would be filled at NASA’s Langley Research Center. There, it was used in the full-scale wind tunnel, or FST, for noise-reduction studies. This research was conducted by Cessna, NASA, and Hamilton Standard in 1975 to evaluate various propeller and propeller shroud designs.

The NASA team removed the front propeller and fitted the 327 with an assortment of three-blade and five-blade options housed within a custom-built shroud. Perhaps surprisingly, the shroud was found to actually increase propeller noise slightly as opposed to reducing it as expected. The airplane was later fitted with Hamilton Standard’s experimental “Q-Fan,” a ducted fan design that was touted to transition from full forward thrust to full reverse thrust in less than one second.

No official record exists outlining the 327’s ultimate fate. The apparent lack of any information beyond the 1975 wind tunnel testing suggests the airplane was scrapped after that. This was perhaps part of a contractual agreement with Cessna, as the company was known to have discarded other prototypes during that era.

We’re left with a smattering of photos and a few piles of technical reports. Coincidentally, with the introduction of electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles and a renewed interest in noise-reduction technologies in the GA sector, the studies might prove valuable even today. And for that matter, a compact, efficient piston twin with the safety of centerline thrust might as well.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox