Don’t Tempt Fate With Your Airplane’s Red Flags

It’s ok to be “a little stitious” and take a hint from the challenges fate throws at you while not tempting them any further.

Wisconsin winters offer many unique flying experiences for new owners – the trick is knowing your limits and pursuing those experiences with discipline. [Credit: Jason McDowell]

In one of my favorite episodes of The Office, several of the employees fall victim to a series of unfortunate events. Exasperated, boss Michael Scott laments the curse that had apparently befallen the workplace. Speaking to the camera, he concedes that while he is not superstitious, he is “a little stitious.”

While I do not take pleasure in identifying with any personality trait of Michael Scott, I must concede that in matters that concern the safety and well-being of my beloved Cessna 170, I too am just a little stitious.

The most recent example of this occurred just a few weeks ago. The ever-present overcast layer of clouds that have been befouling the skies here in Wisconsin for the past month or two had lifted just enough for some VFR flying, the lakes were frozen yet not covered with snow, and I had the afternoon free. I texted my friend Jim, and we made plans to go land on a nearby lake that was hosting ice boat races. It was shaping up to be a magnificent day of flying, and I was excited.

Any pilot relatively new to taildraggers monitors crosswinds like a hawk, and I’m no exception. Whatever servers connecting me to nearby METARs and TAFs must physically glow orange from the strain of having to provide me with constant wind updates on days I go flying. On this particular day, I’d be facing a direct crosswind at my home airport, and it was forecast to be blowing at my maximum personal crosswind limit.

Having endured so many winter weather cancellations, however, my frustration with the weather exceeded my hesitance to push the limits. I made the decision to fly, crosswinds be damned…but I made a mental note that the wind was a potential risk factor; a red flag to bear in mind.

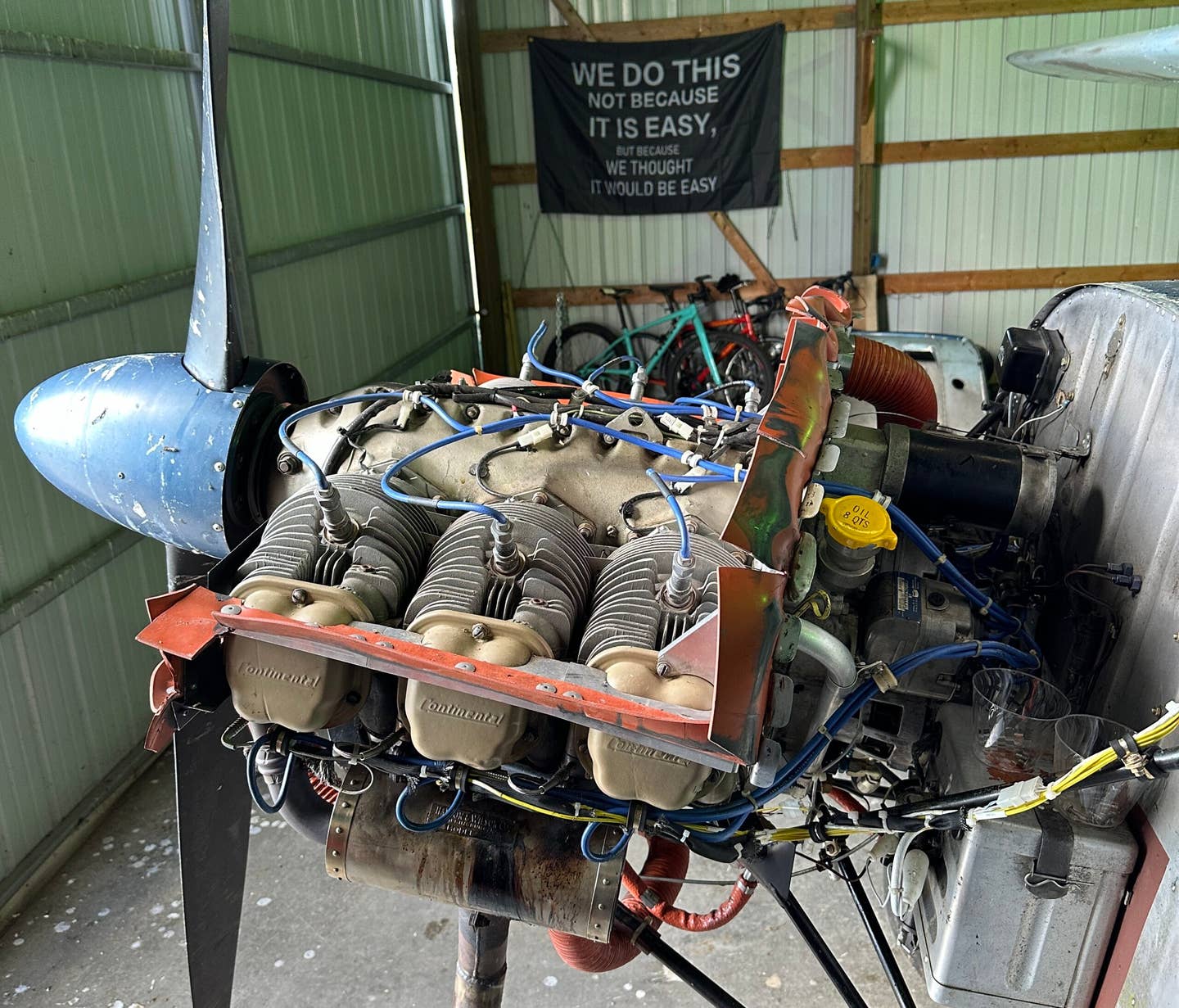

As this was a relatively last-minute flight, I neglected to plug in my engine heater the night before as I would have done with more advance notice. The engine, therefore, was ice cold upon my arrival to the hangar. After about 20 minutes of unsuccessfully begging and coaxing it to start, I heard Jim flying over and radioed him the news - he’d most likely be on his own for the epic frozen lake flight.

With the exception of his healthy physique and his sensible alcohol consumption, Jim is a definitive Wisconsin resident. He’s friendly and never hesitates to lend a helping hand when one is needed. Rather than proceed to the frozen lake, he opted to land and see if he could provide some assistance.

At the same time, a fellow hangar resident walked over to do the same. Upon hearing about the stubborn engine and now dying battery, he brought me his battery charger. We could leave the battery on charge for a little while, he said, and have my engine up and running so I could go fly.

I considered the offer. Yes, I could theoretically get the engine started. But my goal was to land in the middle of the frozen lake, shut down, and watch some ice boat racing. If ever there was a time and place where one wants to be 100 percent positive their engine will start right up, that was it. Red flag number two.

I glanced over at a nearby treeline to see what the winds were doing and observed the waning afternoon light. We had already been planning to fly into the later part of the afternoon. With sunset occurring at around 4:35 p.m., the day was short. And now, with a battery-charging delay, we’d be creeping ever closer to dusk, setting the stage for a return to my insufficiently-lit grass strip. Red flag number three.

Feeling a bit like the universe was perhaps trying to send me a message, I decided to scrap the flight. The helpful hangar neighbor pressured me to use the charger and get into the air, but I declined. It wasn’t even that the red flags were all significant ones—it was almost more a matter of taking a hint from the challenges fate was throwing at me and not tempting it any further. I am, after all, just a little stitious.

Ever the great guy, Jim invited me to join him in his 170. As we were climbing out and heading toward the lake, I started to feel a little embarrassed about my overly-cautious outlook on things and voiced this to him. He wholeheartedly supported my decision, describing how squirrely and tricky the winds had been for him on his way into my strip just a bit earlier. With as much experience as he has in his 170, I’m convinced he could negotiate 40-knot direct crosswinds while playing an accordion and smoking a cigar, but his support made me feel a lot better about things.

We flew to the nearby lake that was hosting the ice boat racing, landed, and shut down. Although I was actively anticipating the slick ice surface, I still nearly suffered a fall while getting out of the airplane. Fortunately, a nearby spectator lent me a spare set of Yaktrax, rubber nets that stretch over the outside of your shoes with tiny carbide spikes on the bottom. These solved the traction problem, and we were able to spend some time walking around and observing the iceboat racing without the inconvenience of a visit to the ER.

Takeoff and landing were uneventful, but taxiing on the ice was interesting. With such a clean, slick surface, Jim was unable to effectively steer on the ground. The tires simply slid over the ice, and blasts of power were unable to steer the tail. The solution was to taxi forward until one of the tires was on top of a thin coating of snow and then use that traction to pivot in that direction. After getting situated and taking off, Jim dropped me off back at my hangar and headed home.

Looking back, sure, I may have been overly cautious that day. And sure, we have to step outside of our comfort zones if we want to grow and develop our skills and experience. But things change when you become an airplane owner. Gone are the days of flying generic rental planes devoid of any personality or personal connection. In their place is your pride and joy that you want to cherish and protect like nothing else you’ve ever owned.

The way I figured it, I had waited about 35 years to own my own airplane. If taking care of it means regularly erring in favor of safety and incurring delays of days or weeks between flights, well, that’s nothing compared to the time it took to become an owner at all. I may be a stitious owner from time to time, but I’m a stitious owner who is ok with taking a bit more time to push the limits.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox