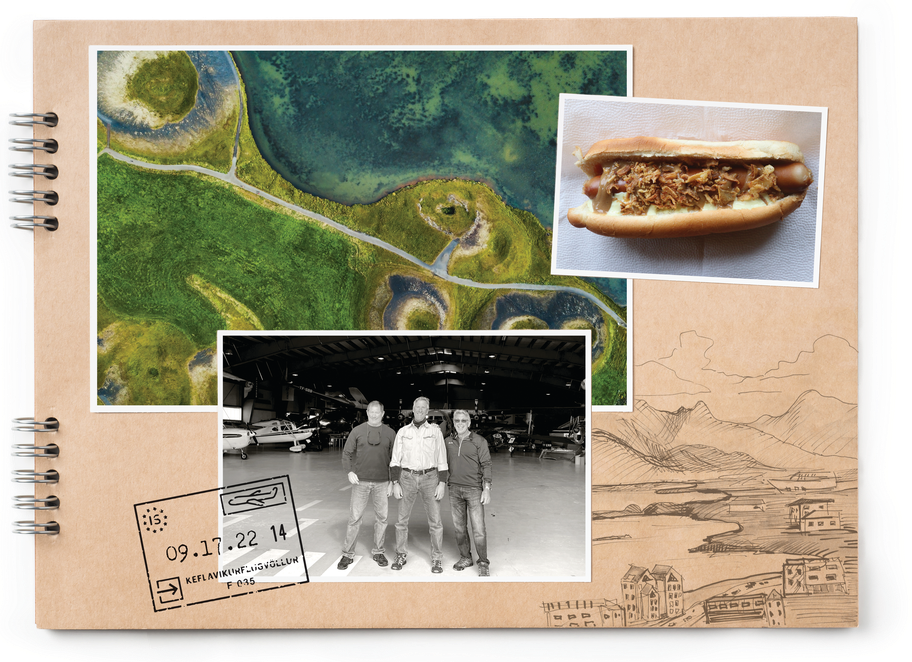

[Photo illustration: Amy Jo Sledge, Images: iStock, Les Abend]

More than a decade ago, a medical emergency while en route from London to New York’s JFK International broke my winning streak of never having to divert across the North Atlantic. A woman was suffering from an unknown cardiac issue. We brought her and more than 200 other passengers on board our Boeing 777 to Keflavik, Iceland. Although we had already communicated with our dispatch team to start the diversion ball rolling, a Boeing 757 crew on an Icelandair flight to the U.S. offered to call their operations desk ahead of our arrival.

The diversion procedures necessary to transit on a route 90 degrees offset from the track system over the North Atlantic can be tedious, but we accomplished the task without creating a traffic conflict, despite the fact my copilot was new to the airplane.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowAfter becoming immediately enamored with the spectacular scenery, despite a mere 55 minutes in the country, I vowed to return as a tourist. Ten years later, my wife and I chose our 25th anniversary for the return visit, accompanied by a group of five friends.

Although I’ve traveled in the back seats of airplanes over the course of my career, somehow this particular trip made me feel more like a passenger. Perhaps the feeling was a result of four years of distance between me and an airline cockpit, or perhaps I was just feeling irrelevant. Or perhaps it was some of the circumstances of the trip. (More on that later.)

So, how does a retired airline pilot function in a passenger role having been the one in control for decades? Well, I’ve got to admit that it’s difficult to avoid glancing to the left as I step through the entry door. Maybe I’ll recognize someone sitting in the pointy end, a former copilot perhaps? Maybe the glance is more of an attempt at somehow feeling reassured that by studying a face, or observing a gesture, or hearing the response to a checklist item, my confidence in the crew is reinforced. Or just maybe I suffer from self-reproach, having the need to see just how much younger the crew is than me.

I usually annoy my wife with opening the window shade so as to “assist” from the inside with any operational concerns, a request she patronizes unless glaring sunlight pierces through. We both make it a habit to review the emergency card to determine our nearest exit, and then visualize how to operate that exit. I will admit to being a PA critic. If the captain can’t string a few sentences together that instills confidence, makes sense, or is audible, I’ll quietly mutter my opinion.

I attempt to determine our takeoff runway based on my limited view of our taxi route. Why? If an emergency evacuation is necessary, I’ll have some situational awareness to assist anxious passengers...and...well...maybe knowing where we are is still part of my airline pilot psyche.

In the same manner that flight attendants are trained, my eyes remain open during the takeoff roll. After rotation, I note the time and listen for an engine to cough. Satisfied that the airplane is flying normally, I take advantage of the climb deck angle to catch a snooze. The sound of a single chime indicates climbing through 10,000 feet msl and the end of the sterile period, which signals the end of my accuracy on altitude.

Throughout the flight, I can’t help but people watch. Despite media reports of raving lunatics having meltdowns, I’ve experienced mostly friendly and considerate folks. Now that I spend more time in the back of the bus, I am even more grateful for the veteran flight attendants who handled my testy passenger situations without ever requiring a cockpit consultation.

With most people biologically connected to their electronic devices, an open window shade seems to be a rare occurrence. An open window shade is tantamount to having a loud conversation in a library. In that regard, my geographic orientation to the outside world during the descent, approach, and landing is limited. On the occasions that I recognize a familiar landmark, I’ll assist the crew by non-verbally advising when to deploy flaps and the landing gear. No one listens.

Unless the touchdown drops masks or rattles my fillings, I don’t critique. You can’t judge without being aware of the challenges that the flying pilot encountered. If the touchdown was a deftly accomplished grease job in adverse weather conditions, an “attaboy” is warranted while deplaning.

Back to Iceland. Our group spent 10 days together on a self-driving tour, traveling counterclockwise around almost the entire island. Two retired airline pilots and one active airline pilot shared the driving and navigating with a surprisingly high degree of success. The scenery was spectacular. The food was delectable—even the Icelandic hot dog had merit. The people were affable and accommodating. The service was superb. The language was...well, let’s just say the locals were apologetic. Thankfully, English was widely spoken.

Unfortunately, the departure day back to the States didn’t end well for my wife and me. My mounting symptoms of congestion, coughing, and a sore throat culminated in a positive COVID-19 test for both of us. We were grounded. The hotel allowed us to check back in, but room availability for the next week was limited. Between coughing fits the following day, I secured lodging at another location in downtown Reykjavik. My wife was 36 hours behind me with her symptoms. Except for one lucky member of our anniversary tour group, everyone else tested positive shortly after their arrival home to the U.S.

Icelandair proved problematic in that the last-ever nonstop to our origination airport of KMCO (Orlando International) was the flight we had missed. With the airline having a code-share agreement with JetBlue, a connection seemed an easy solution. But no. Icelandair’s policy was only to return us to a destination that was on their route system, which was Baltimore, JFK, or Boston.

Despite my COVID-influenced phone conversation attempting to reason with the agent that none of the aforementioned destinations were an acceptable distance from our origination airport, we were on our own. So, this is what it’s really like to be a passenger?

After almost five days of isolation, when my wife and I felt relatively human, we happened upon Icelandair’s headquarters near the Reykjavik Airport (BIRK) during a walk. An agonizing 90 minutes later, we trotted away with a negotiated settlement of 50 percent off JetBlue’s connection fare to Orlando from Boston. Perhaps it was my story of the diversion 10 years prior that tugged at the agent’s heart. Probably not—otherwise we would have paid nothing.

The good news: Despite the circumstances, my wife and I managed to salvage the extended stay and had an enjoyable experience once the virus was in the rearview mirror. The checkbook balance is still in pandemic recovery stage, but we’ll survive.

We departed Keflavik Airport (BIKF) almost three weeks after we had arrived on a Boeing 737 Max 8, which seemed ironically appropriate. (It’s time to stop stretching the airplane, but that’s fodder for another story.) Like a surgeon donning a hospital gown for his own surgery, being a passenger is probably not my forte.

This column was originally published in the December 2022/January 2023 Issue 933 of FLYING.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox