World’s Largest Airplane Flies a Fifth Time, Moving Closer to Hypersonic Tests

The world’s largest airplane, Stratolaunch’s Roc, took off from California’s Mojave Air and Space Port (KMHV) Wednesday, flying for the first time with a new pylon crucial to the carrier aircraft’s success.

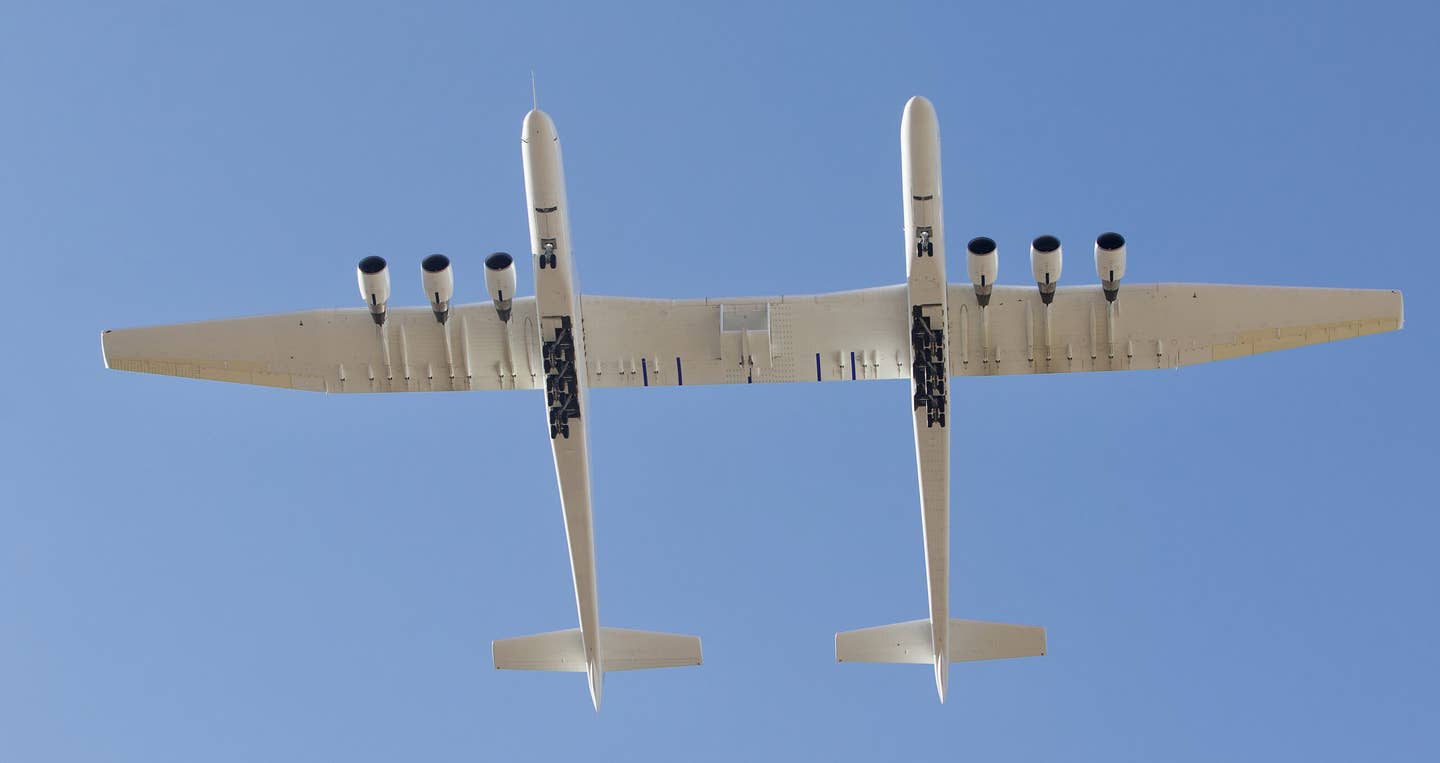

A view of Stratolaunch’s one-of-a-kind airplane as it flew overhead Wednesday at California’s Mojave Air and Space Port. [Courtesy: Stratolaunch]

The world’s largest airplane, Stratolaunch’s Roc, completed its fifth flight from California’s Mojave Air and Space Port (KMHV) Wednesday—the first test of a pylon crucial to the carrier aircraft’s success.

Under clear skies and calm winds, Roc’s six Pratt & Whitney PW4056 turbofans and 385-foot wings lifted the 500,000-pound, twin-fuselage jet above Runway 30 at about 7:40 a.m. PT. In its longest test flight so far--nearly five hours--the airplane touched down back at KMHV, at 12:37 p.m. PT.

Pilots Evan Thomas, Steve Rainey, and flight engineer Jake Riley flew Roc with a 15-foot-by-15-foot pylon hanging from the jet’s 95-foot center wing, testing the device for the first time, as well as several other onboard systems. Testing took place at multiple altitudes, including FL150 and FL225, while achieving speeds around 180 kias.

With a Cessna 550 Citation Bravo chase airplane flying nearby, the crew retracted and extended Roc’s eight landing gear as they did during its previous mission in February. But it was the 8,000-pound pylon that was getting much of the attention.

“It’s exciting to have the pylon on now,” Stratolaunch chief engineer Scott Schultz told FLYING. It represents Roc’s transformation from an airplane to a mission systems airplane. “I’m excited, not only about the pylon, but the fact that we’re turning it into a flying launch pad.”

The pylon’s importance is difficult to overstate. It’s the linchpin of Stratolaunch’s eventual business model to launch small, autonomous, rocket-powered, hypersonic testbeds from altitudes around 35,000 feet. Without a pylon—the critical point where a testbed attaches to the airplane—Roc’s business model falls apart.

Talon-A is a reusable Mach 6 testbed. Plans call for a Talon-A separation test article—measuring about 28 feet long—to be mounted on Roc’s pylon for a separation test later this year. The pylon also includes new data acquisition systems for Talon-A, as well as sensors.

Test Flight Five

Engineers will use data from Wednesday’s flight to look holistically at how Roc performed with the pylon, including any adverse flying qualities.

“So one of the things we’re looking at is how this pylon affects the airplane as a whole,” Schultz explained. “How much rudder per beta? How much elevator per alpha? Are we on predictions from an alpha versus CL [lift coefficient] curve, which is how much lift the airplane makes with the angle of attack.”

Engineers documented the visual flow field surrounding the aircraft, using tufts to measure aerodynamics on the pylon surfaces.

Practice makes perfect! Building on the landing gear testing that occurred during the fourth flight test, the team is continuing tests gear operations through mid-air cycling of the system. pic.twitter.com/Kb5jZigx8w

— Stratolaunch (@Stratolaunch) May 4, 2022

“We’ve also got a significant amount of accelerometers on this pylon and throughout the airplane to measure buffeting coming off of the pylon that would shake the rest of the airplane,” Schultz said.

In addition to cycling landing gear and monitoring the pylon, the crew also tested the airplane’s autopilot and yaw augmentation system.

Essentially, the yaw augmentation system is similar to what many GA or bizjets have. It’s basically an aileron-rudder interconnect and a yaw damper combination.

Pilot Evan Thomas told FLYING last December that Roc’s yawing characteristics are the result of adverse aileron drag, and come from “the deflection of the ailerons and the differential of the lift. You also get some raw yaw due to the roll rate of the airplane—a function of the wings rotating about the longitudinal axis of the airplane.”

When Scaled Composites designed Roc—or Model 351 as it was officially designated—the airplane was intended as a universal air-launch carrier for multiple payloads up to 550,000 pounds. “It’s a really universal system that’s hooked up on four major points on the airplane,” Schultz said. The points are really close to spars, but they’re not right on a spar. … With the spar shape and construction size, sometimes that’s impractical.” Instead, the points join with ribs that are adjacent to spars, but as close to spars as possible.

About the Pylon

The pylon is made of metal and some carbon skin, Schultz said, and will not be the final iteration. “It’s designed for a fairly light launch vehicle like Talon, however, we’ve baked in significantly more weight capability and margin than Talon—but yet still it’s not a half-million pound rocket structure quite yet.”

Central to its design is a canoe-shaped element called an adaptor—the mechanism that connects Talon-A testbeds to Roc’s massive wing. On the ground, when crews mate Talon-A with the pylon, the adaptor detaches from the pylon’s “wing” and is lowered down with winches. The Talon-A is then attached to the adaptor and then winches back up to join with the pylon.

“We’ll likely end up using a different pylon for most of our big launch vehicle campaigns, which goes back to the airplane’s universal design to basically take whatever pylon you want to put on it. You swap pylons much like an adaptor for an F-15. On this, you’d end up swapping pylons for the different missions.”

Increased Operations Tempo

Stratolaunch is expected to increase its operations tempo for Roc test flights. Beginning this year, Roc has flown in January, February, and now in May. Expect this pattern to increase further moving forward.

As the Pentagon seeks to develop hypersonic weapons, Stratolaunch CTO Daniel Millman is calling on the U.S. military to consider flight testing technologies on low-cost testbeds that are “regular, routine and reusable.”

Although Roc isn’t expected to be operational until mid- to late 2023, Stratolaunch already has a hypersonic research contract with the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory.

The company also has agreed to provide “threat replication” for the Pentagon’s Missile Defense Agency to help scientists understand how to engage and intercept hypersonic threats. Last month, Stratolaunch opened a permanent Washington, D.C.-area office to support the acquisition of future contracts.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox