The First Lesson in the New Airplane? Overly Eventful

A ‘colossal screwup’ leaves our rookie reeling, and wondering if there’s more to come.

A quiet grass strip is a welcome destination…particularly when an urgent precautionary landing is in order. [Photo: Jason McDowell]

Editor's note: This is part one of a three-part series.

As a rule of thumb, you really don’t want your first lesson in your first airplane to be an eventful experience. Memorable, sure. But otherwise, you want a predictable, run-of-the-mill flight to welcome you into the ranks of airplane owners. That’s what I was hoping for back in August of last year, but as it would turn out, it’s not what I’d receive.

After taking delivery of my 1953 Cessna 170 in July and obtaining help from a fellow 170 owner to fly into and out of Oshkosh for Airventure 2021, I networked with friends to locate a local flight instructor so I could become checked out and proficient in my new machine. The search took some time, as not every instructor possessed the requisite 170 experience my insurer deemed necessary. Eventually, though, I was introduced to a fellow named Pete.

““Is that a normal cylinder head temperature for this engine?” Pete asked.”

A banker by trade, he pursued his ratings on the side and now instructs for fun in all sorts of aircraft types. He did have the necessary 170 time, and my confidence was bolstered when I learned he also routinely flew an old Stampe SV-4C biplane. I’ve never flown a Stampe, but I reasoned that if a pilot can successfully wrangle a 1930s-era military trainer with a thoroughly bizarre braking system, they can also most likely operate a Cessna taildragger in a relatively safe manner.

We arranged to meet on a weekday afternoon at the small, privately owned grass strip where I had been keeping my airplane. The winds were calm, and although the ceiling was too low to fly, the forecast indicated it would soon improve. I pulled my airplane out anyway, conducted a very thorough preflight inspection, and welcomed Pete when he arrived a short time later.

We exchanged pleasantries, talked about the airplane, and discussed my training goals. The ceiling wasn’t lifting as forecast, though, so we opted to run into town for a quick bite to eat while we waited for that to happen. I pushed the airplane back into the hangar, and as it was an open hangar without a door, I carefully placed the cowl plug back into place to prevent birds from nesting in the engine compartment.

A couple of burgers and Cokes later, the ceiling finally lifted enough to allow our flight to proceed. After an abbreviated preflight inspection, we trundled out to the runway and headed out to practice some stalls and slow flight. It was remarkably smooth, and there was no other traffic to be seen.

Pete noticed it first. We were about 8 miles away from the airport. I was performing some steep turns and focusing on maintaining altitude perfectly in the hopes of finding the satisfying bump of our own wake.

“Is that a normal cylinder head temperature for this engine?” Pete asked.

I glanced over at the gauge and felt my stomach drop. I wasn’t intimately familiar with my Continental C-145, but I knew 550 degrees was most certainly not good.

Instinctively, I reduced the power and returned to straight and level flight. The CHT was obscenely high, but for the time being, the engine wasn’t exhibiting any obvious problems. The mixture was already full rich, and the airplane lacked cowl flaps, so the only obvious solution was to nurse it to the nearest suitable airport at a reduced power setting. So that’s what we did.

Fortunately, a wonderful 3,100-foot grass airfield was only about two miles away. It was a private airport, but Pete apparently knew everyone in the area and assured me we would be welcome to drop in, especially under the circumstances. The CHT crept downward from its terrifying peak, but it remained uncomfortably high. I felt good about our prompt decision to divert.

My landing at the airfield wasn’t my best work, but considering the very realistic distraction with which I had to contend, I gave myself a pass. I let the airplane gradually come to a stop, and when I added power to taxi clear of the runway, that’s when it popped up into view. The cowl plug. Still in place, right where I placed it before we left for lunch.

Unlike modern cowl plugs that include a cord to be wrapped around the propeller or small flags to keep them visible from the cockpit, the cowl plug I was using lacked any sort of safety device to prevent a pilot from flying the airplane with it installed. It was a simple piece of flat plastic, made from scratch by the previous owner…and as I had just demonstrated, it would happily remain in place if a fool such as myself was to leave it in place before flight.

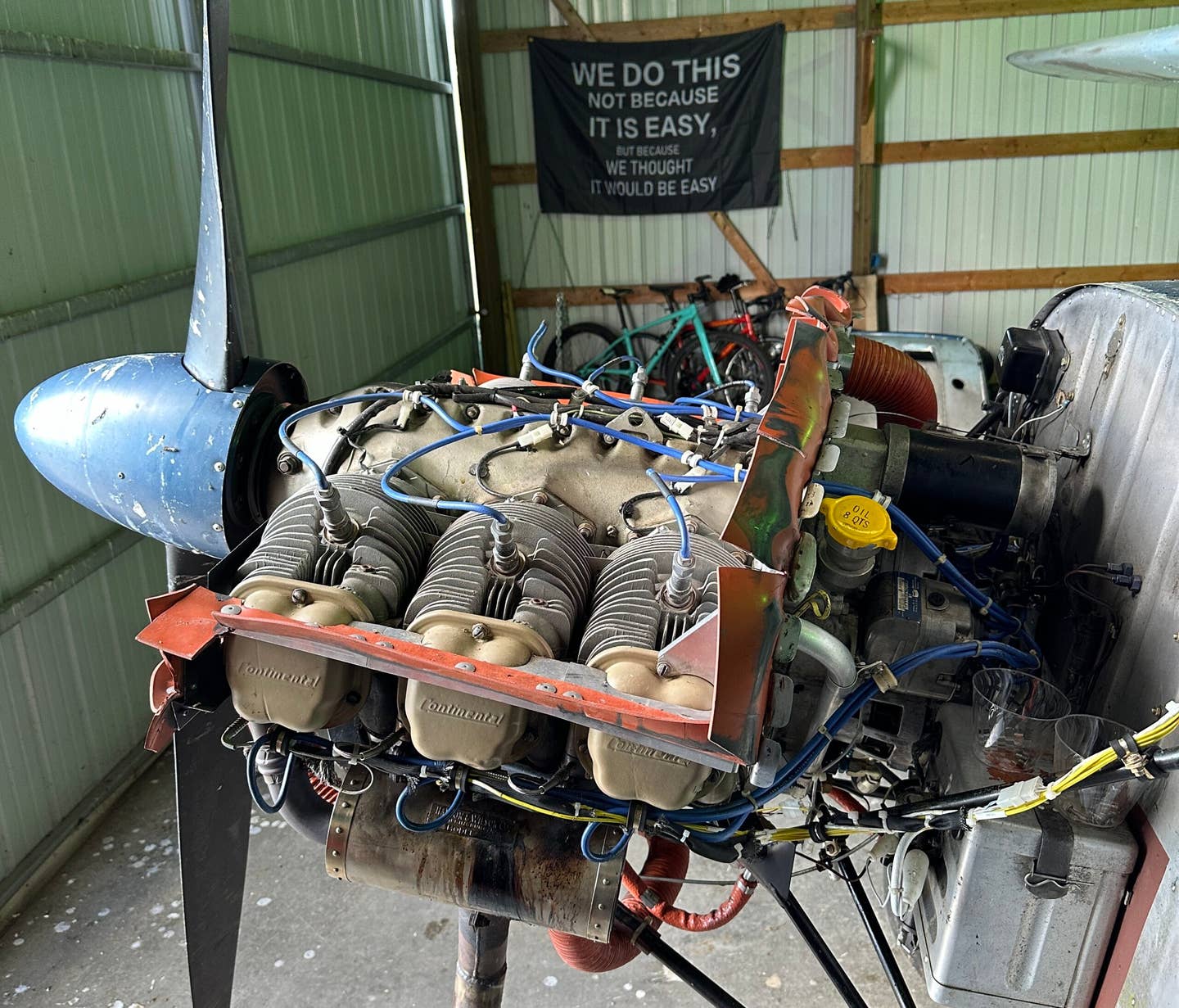

I pulled off to the side of the runway and shut the engine down. Pete and I hopped out and opened up the cowl to help the engine cool. We watched wisps of smoke rise from the engine and dissipate into the breeze as old, spilled oil burned off of the engine block. Neither of us spoke. Only the ticking of cooling metal punctuated the otherwise silent airfield.

Though I remained standing next to my beloved machine, I shrank into myself, sinking into a pit of shame and humiliation as I contemplated what I had done. Did my stupid oversight just ruin a perfectly good engine? Were my years of working overtime, saving and scrimping, just flushed down the toilet for no good reason? Did I really just kill my airplane on my very first lesson?

Recognizing my self loathing, Pete did his best to put things into perspective. He pointed out that the engine had probably only been truly hot for a few minutes. He said it was a simple oversight, and suggested that after it cools down, we’d see how it runs.

As I continued to reflect upon my idiocy, a pickup truck pulled up. Pete instantly recognized the driver as a friend and introduced me. His name was Dan, a Cessna 182 owner based there at the field. While working in his hangar, he saw us shut down on the side of the runway and came out to check on us.

I didn’t know it at the time, but a few months later, Dan would become my savior, rescuing me from the pit of mechanical troubles into which I had descended.

After the engine had cooled sufficiently, we bade Dan farewell and hopped back into the airplane. The engine started normally, and though the oil pressure was predictably low given its temperature, it was well within limits. The runup also was uneventful, and after some careful monitoring, we decided to head back to my home airport.

The takeoff went fine, and the airplane performed beautifully. I briefly considered continuing with some maneuvers, but recognized I was not in a good mental state and informed Pete we’d be calling it a day. Pete concurred, and we made it home without incident.

Buoyed by our successful flight home, Pete scheduled a follow-up lesson for the following day. Still reeling from my colossal screw up, I agreed…but I had a feeling I wasn’t out of the woods just yet.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox