Sizing Up Your New Aircraft

Ergonomics is one aspect few people consider in selecting an airplane to buy.

The tiny Quickie—an innovative way to convert 18 hp into 100 knots and 100 miles per gallon but only accessible to smaller pilots. [Credit: Jason McDowell]

When evaluating the many concerns involved with selecting an aircraft type to purchase, most people cover all the bases. Engine time and health, hangar availability, insurance cost, training requirements, and similar issues generally play a part in the decision—and for good reason. They’re all important elements that can significantly affect the ownership experience.

One aspect that few people take into consideration—early in the process, anyway—is ergonomics. This is primarily only a concern with particularly large and small pilots, but it’s an important one nonetheless. Certain aircraft types are simply incompatible with people of certain sizes, and these are pilot/machine combinations to avoid.

As a larger person who tends to require more shoulder room than most, I learned early on that I’m not suited to certain types. Paired with an instructor of similar size during my primary training in a Cessna 152, I assumed it was customary for both occupants to have to inhale deeply to enable both doors to close. And I assumed it was normal to then have very little (comfortable) range of motion after being squished inside.

While these uncomfortable realities are perhaps not terribly uncommon, they’re not entirely necessary, especially when buying your own airplane. So, when I fell in love with the flying characteristics of the Cessna 140, I ultimately decided to save my money for another couple of years so I could afford the larger and decidedly less cramped Cessna 170. It was money well spent. Although I would never describe the 170 as a roomy airplane, it improves greatly upon the discomfort of the 140.

But a more interesting question is what types are especially well suited to particularly large or small pilots. Some dedicated investigation can reveal some compelling types that your size, large or small, can unlock. These might be types that you’d never have otherwise considered.

The North American/Ryan Navion was a pleasant surprise when I reviewed it for an upcoming installment of FLYING’s “Air Compare” feature in the print edition. With a cabin that’s spacious enough to enable passengers to move between the front and back seats and a number of controls that require a good reach to access, larger pilots will feel as though the airplane was made just for them.

Similarly, the Cessna 180, 182, and 185 all have quite tall instrument panels and heavy controls, particularly the elevator in the flare with full flaps. They have ample cabin space and enough useful load that baggage and a second sizable occupant is rarely a factor. Like the Navion, these airplanes are entirely flyable by people of all sizes, but larger pilots will likely find them a comfortable, natural fit.

Most large pilots don’t even consider smaller machines like the Luscombe for good reason. The tiny side-by-side cabin is only 39 inches wide. But there’s a sneaky way into Luscombe ownership for larger folks, and it comes in the form of the rare T8F “Observer.” Equipped with tandem (one seat in front of the other) seating, this placement provides twice the shoulder room as a standard Luscombe. A relatively limited useful load remains a restriction, however, and larger pilots generally have it worse than smaller ones because of this.

Speaking from experience, larger pilots look at our bantamweight colleagues with a healthy dose of envy. How nice it would be to instantly have an extra hundred pounds of useful load, or alternatively, less weight with correspondingly better performance. Our abilities to manage heavy control forces and move airplanes around on the ramp with ease are quickly forgotten as we observe departure-end obstacles looming ever closer during one of our luxuriously ponderous climbs.

In addition to enjoying better performance and load-carrying ability, smaller pilots enjoy a backstage pass into a number of correspondingly small aircraft types. The achingly cool Culver Cadet, for example, with its beautiful elliptical wing and retractable gear, offers only about 35 inches of cabin width to its two occupants seated side by side. Even average-sized pilots find this to be cramped, so to be able to fly one around comfortably is a privilege indeed.

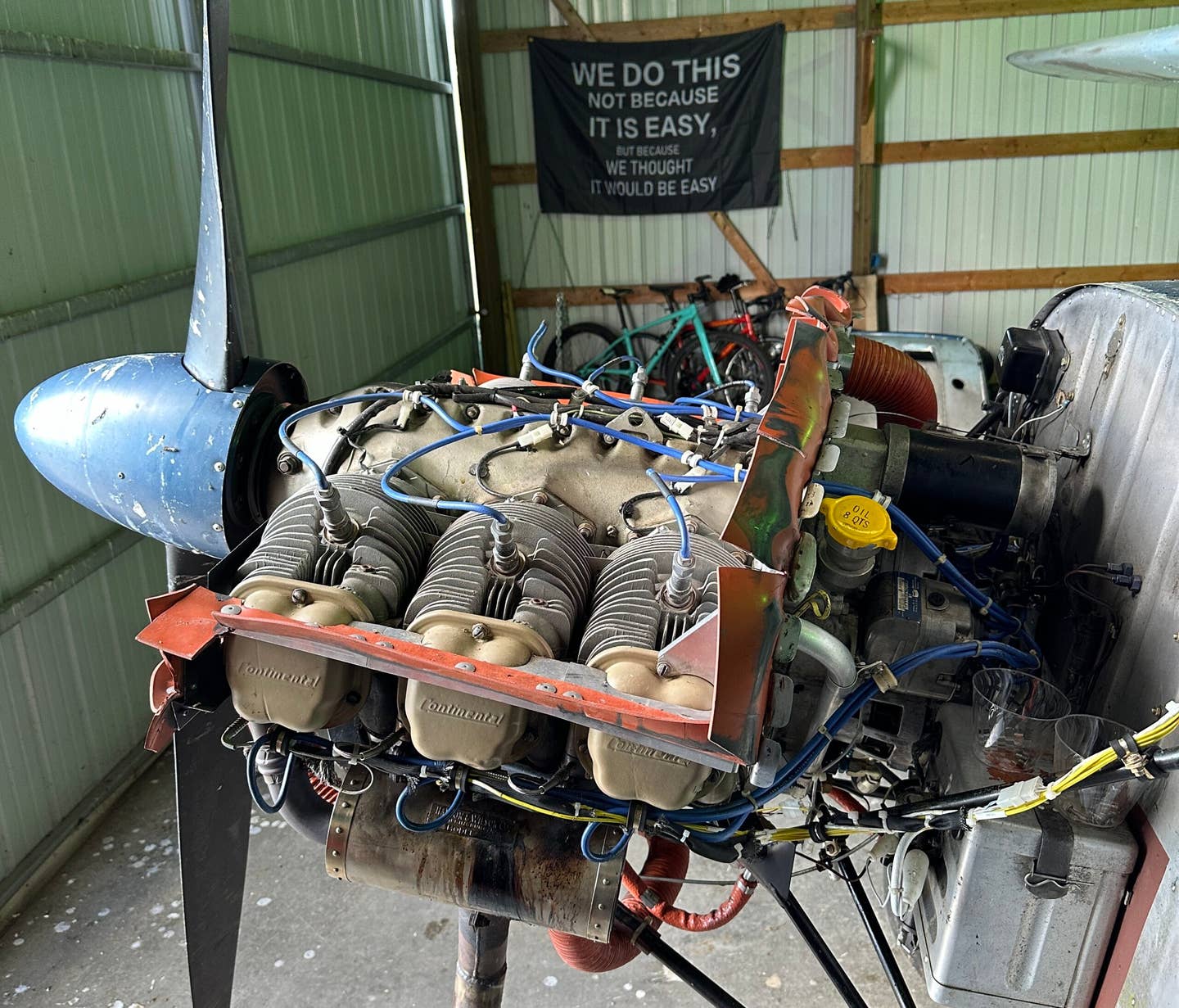

The single-seat Mooney M-18 Mite is a type that similarly only accommodates smaller people. An extreme example is the Quickie, an even tinier single-seat—and experimental—aircraft that, with an 18 hp engine, boasts a max cruise speed of 115 mph (100 knots) and can achieve 100 miles per gallon. While either of these can carry a slightly heavier pilot, the cramped cabin limits access to smaller ones.

Not all is fun and games for our smaller friends, however. Fighting an old, stiff fuel hose while climbing up onto a high-wing aircraft isn’t fun for anyone and may be nearly impossible. Getting into and out of a taildragger with big Alaskan Bushwheels can feel like it requires crampons and a rope. And simply moving an airplane around on the ramp or into and out of a hangar, particularly in slippery winter conditions, can become futile.

The biggest opportunity for the prospective airplane buyer is to take these sorts of concerns into account early in the shopping process. Talk to others of similar size in online forums. Better yet, attend as many fly-ins as possible. There, you can try airplanes on for size and chat with owners of similar size to make a decision you’ll be happy with for the long term.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox