Rosie the Riveter—an image of a woman doing what was traditionally a man’s job—is also a reminder of the gargantuan objectives that can be achieved by innovating and then cooperating. [Credit: Library of Congress]

As an early teen I was captivated by images of Rosie the Riveter. She impacted me on multiple levels. For starters, I wanted to marry her, and alongside Linda Carter, of Wonder Woman fame, elicited my earliest feelings of...well, you know. Something about those coveralls, the rivet gun, and her ability to do what was traditionally a man’s job. But she also hit me in another way. She gave me a larger sense of wonder about human beings and our ability to adapt and work together (even though we were at war with another group of humans—my reasoning was still squarely in its nascent stages). This idea that we could achieve gargantuan objectives by first innovating and then cooperating, struck a chord. A slight libertarian streak formed in me. Innovation begins with one person. It always does.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

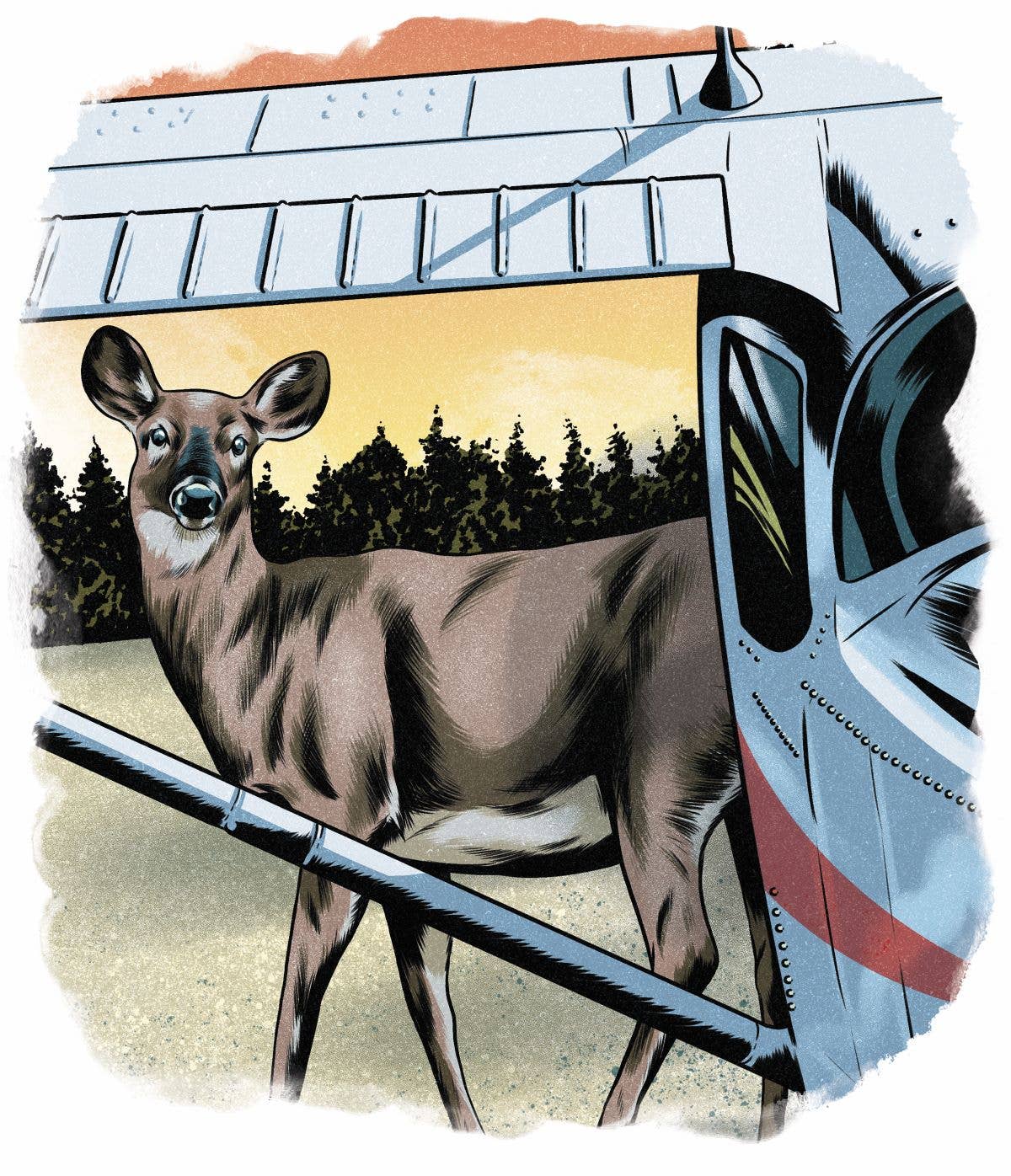

Subscribe NowMy beloved V-tail Beechcraft Bonanza has, for years, had a looming issue that is now finally coming to a head. Not just mine. Every V-tail ever made. It concerns its exotic magnesium ruddervators. The gauge and stock of the alloy used by Beech all those years ago is no longer produced. Anywhere. Spares have become impossible to come by, and we have arrived at a place where a minor hangar-rash incident can be determined a total loss by the insurance company.

In comes Tom Turner of the American Bonanza Society, offering an incentive to whatever brilliant minds are sleeping out there to come up with a solution. He created the ABS/ASF Maciel Ruddervator Prize with a $500,000 cash award to the first person who “designs and obtains FAA certification of an alternative to original ruddervator skins or a replacement for the entire ruddervator assembly...”

Half a million dollars got more than a few individuals’ attention. People began thinking, then talking, and then doing. There are currently a few different solutions coming down the pipeline (as of this writing, even Beech has jumped back into the game, fabricating the skins once more. The contest seems to have sufficiently shaken Textron Aviation enough to make them see their customers’ needs).

Along with Rosie, another woman I became infatuated with as a youth was Ayn Rand. I got swept up in her ideas of individualism. I’ve since come to understand the flaws in both her philosophy and personal views, but let’s separate the artist from the art for a moment. The idea she planted in my head was that an individual (read: American) could do whatever they (read: he) dreamed of.

I responded strongly to this idea, and though I started my career as a public servant, I knew I wanted to one day create something original and be the master of my own destiny. I wanted to marshall others to help me in my endeavors. As a filmmaker, I start with a kernel of an idea. I play with it and shape it, and ultimately turn the idea into a screenplay. After that, I need help. Lots of it. Making a film requires hundreds of people to help me execute my vision. I don’t see it as any different than starting a business or coming up with an invention that then needs to scale up to production. It starts with me but becomes something much bigger.

George Braly of General Aviation Modifications, Inc. (GAMI), has been telling me for years that he has an unleaded fuel replacement for 100LL. If I’m honest, I doubted him. I’d been to his shop in Ada, Oklahoma, and seen his expertise firsthand. His work on detonation and the entire combustion process is unparalleled. I swear by his GAMI injectors. But I assumed only a major petroleum company could pull off something as big as a 100LL replacement, and even they seemed unable to do so. My rationale was that if it could be done, someone would have already done it. How could George pull this off in an airplane hangar in Oklahoma? I didn’t see any glass beakers lying around when I was there. Not even a single lab coat.

While I never expressed any of my doubts to him, I imagine they would not have made one bit of difference. George was undeterred. He knew what he wanted to do, and he did it, detractors be damned. His formulation is the first to pass FAA muster and is on track to be the primary fuel replacement for all of us in the spark-fired piston world of GA. His solution will benefit all of us and, I imagine, himself—handsomely—as well. As with the ruddervator prize, money continues to be a strong incentive for creative minds everywhere. And that’s okay, as the ends really do justify the means here.

It all begins in one primate’s brain. That moment when you’ve closed your eyes and are about to fall asleep or are in the middle of a shower, hair full of shampoo. You’re not even working on the problem when it happens. Not consciously. You may have even given up on it entirely. And then the lightbulb goes on. The solution appears magically, the brain having done all that beautiful work in the deep background. The moment is so out of our control that we feel we had no part in it—as if it happened to us. Once the idea enters consciousness, the creator will not stop until it comes to fruition. It doesn’t matter how many people say it can’t be done. This is what innovation looks like.

It is then that the Rosies of the world come in and help finish the job. This might sound reductive and romanticized, but it seems to me that when there is a common problem and value alignment over it, even the most disparate groups of people can come together to find a solution. As a species, we are very good at problem-solving, so long as we don’t get in our own way.

In the final scene of my last film, Bleed for This, boxer Vinny Pazienza explains to a reporter that the biggest lie he has ever been told is, “It’s not that simple.” In his case, he is referring to people’s doubt about his attempt at a long-shot comeback after a broken neck he suffered in a car accident. He tells the reporter: “If you just do the thing they tell you you can’t, then it’s done. And you realize that it is that simple. And that it always was.”

This article was originally published in the February 2023 Issue 934 of FLYING.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox