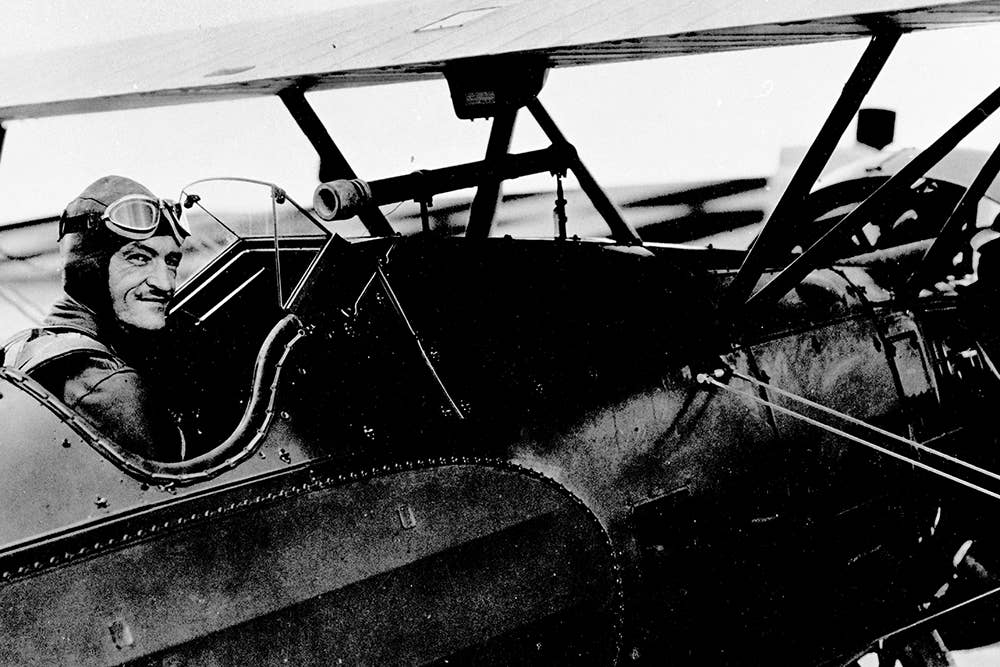

Captain Claire Chennault at the Air Corps Tactical School, Maxwell Field, Montgomery, AL, in 1932. [Courtesy: National Museum of the U.S. Air Force]

On December 20, 1941, an all-volunteer group of American mercenary pilots took on Japanese bombers in their first air combat mission to protect China.

By day’s end, the American Volunteer Group (AVG)—better known as the “Flying Tigers”—would go on to down nine out of 10 Japanese bombers in the first of many air battles in a seven-month campaign that helped block Japanese expansion into China.

The Flying Tigers’ legend is one that continues to represent military cunning and a special brand of American grit. It is a story of how an irascible commander trained a group of U.S. volunteer military pilots to beat an adversary that was better trained and outfitted through exploiting weakness, all while wearing the patch of another country.

Here are five things you should know about the Flying Tigers:

1. One man was behind the genius of the AVG’s winning air strategy: Claire Chennault.

U.S. Army Air Corps aviator Claire Chennault is remembered for many things, among them being opinionated and more than a little daring.

“Captain Chennault was known to fly his P-12 upside down under the Highway 31 bridge on his way home for lunch,” Fred Schramm, Air University History Office historian, once said. “He would also take his P-12 to Louisiana for the weekend on hunting expeditions,” he added. “He would load his dogs in the cargo section of the plane and fly home with his game strapped to the wing of his plane.”

Chennault was also not known to have an agreeable relationship with his superiors in the Army Air Corps. As he exited military service on a medical discharge in 1937, the Chinese government recruited him as an adviser for its air force.

“The day after he left the Air Corps as a captain, he was on his way to the West Coast to head to China and to become their air adviser,” said Tripp Alyn, chair of the Historical & Museums Committee AVG Flying Tigers Association. “They gave him the title of the rank in China of colonel, so an American captain suddenly becomes a colonel in the Chinese Air Force.”

When he arrived in China, Chennault was given a Curtiss P-36 Hawk, which he flew during reconnaissance missions observing Japanese air operations.

“In this aircraft, he went up and he observed the Japanese, and made copious notes,” Alyn said. “He observed their formations and their attack doctrine,” including their altitude, airspeed, direction, and how they attacked. “The Japanese were true to their doctrine, and they were very consistent and very predictable.”

The experience led to Chennault’s theories of defensive pursuit.

2. The AVG was created to defend China.

In the late 1930s, Japan’s expansion campaign in China raged on. Japanese bombers attacked Chinese cities, killing civilians indiscriminantly.

“Japan always thought they were invincible,” Alyn said. “They flew against the old aircraft of China with impunity.”

Chennault and a delegation of Chinese officials turned to the U.S. to ask for help.

“They reached out to us for help, but we couldn’t send them our units or we’d be at war,” said Bob van der Linden, a curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. “The United States was desperately trying to stay neutral, and stay out of wars, but also … trying to keep the Nazis at bay and trying to keep the aggression of Imperial Japan at bay,” he said. “[President] Roosevelt understood that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were a threat. But he also knew we could not declare war.”

Roosevelt could, however, support the Chinese government in its defense against Japan in another way that would also help keep China in the war. The U.S. would support the creation of the American Volunteer Group, an all volunteer unit of 100 reserve military pilots who would be allowed to resign their commissions to travel to China to serve.

“At the time, the American public was quite pacifist and non-interventionist through the late ’30s,” said Gene Pfeifer, curator and historian at the National Museum of World War II Aviation. “It was very difficult for [Roosevelt] to see a way where he could meaningfully help the Chinese before we got into the war with the Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor. And this was one way that he felt he could make a meaningful contribution to checking Japanese expansionism in the Pacific.”

By the summer of 1941, the AVG began to mobilize in Burma as Japan launched a massive bombing campaign against Chinese cities. One such bombing occurred on December 19, 1941.

The next day, on December 20, the AVG received an alert that 10 Japanese bombers were en route. Information relayed by spotters confirmed their course toward Kunming. Recognizing the play, Chennault sent two squadrons up—one orbiting over the city of Kunming at an altitude that could be seen by the Japanese pilots, and the second ready to pounce.

“What he did was ingenious,” Alyn said. “They knew that an attack was eminent on them,” and they jettisoned their bombs as they turned to return to their home base.

“Because of the note locations, Chennault knew where they would be jettisoning their bombs,” as well as the course they would take and the altitude.

A squadron was ready for them, attacking from out of the sun so that the Japanese bombers would never know what hit them.

“Chennault taught the AVG to use a diving attack, to dive, shoot, then dive away,” Alyn said. The strategy maximized the rugged speed of the P-40s while limiting the time an adversary could fire back.

At the end of the day, only one of the 10 Japanese bombers made it back to their base.

“When the Americans returned to Kunming, the Chinese people were so thrilled. For the first time the Japanese had been shot down,” Alyn said. “The newspapers reported, ‘They’re fighting like tigers—Flying Tigers.’”

3. The AVG operated for only about seven months.

By July 1942, the AVG reportedly shot down or destroyed 297 enemy aircraft for a ratio of 20-to-1 and produced 20 ace pilots who shot down five or more. The Flying Tigers, which was composed of 311 pilots, ground crew and trainers, suffered 23 losses, including 22 pilots.

“It’s only seven months, but that was perhaps the most precarious seven months of the war in the Pacific,” van der Linden said. The U.S. had suffered an attack at Pearl Harbor and lost the Philippines. The U.S. Navy had been “knocked back on its heels,” and the Japanese Navy was operating unopposed in much of the Pacific.

The Flying Tigers turned the tide.

“Yes, they were fighting for nationalist China, but national China was our ally. And that was just fine. And they were striking blows against the Japanese,” van der Linden said. “America was still fighting back, and that was an extraordinary morale booster at home.”

4. The P-40 and AVG helped prove Chennault's theories of defensive pursuit.

On paper, the deck was stacked against the AVG. They were going up against Japanese Navy fighter pilots flying Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeros, a fast and nimble single-seater monoplane.

The AVG, by contrast, had Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, a ground-attack aircraft that was plentiful, but flirting with obsolescence.

“The United States was desperately trying to stay neutral, and stay out of wars, but also … trying to keep the Nazis at bay and trying to keep the aggression of Imperial Japan at bay.”

Bob van der Linden, curator, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

“It performed very well throughout the war, but most of the aircraft it went up against were better either in terms of visibility or firepower,” and were slower than other fighter aircraft, van der Linden said. The P-40 couldn't turn with the Zero. What it did have, however, was a good range, coordinated controls and flew well.

The P-40 was “very much a pilot’s airplane,” he said.

“What the tactics of the Flying Tigers under Claire Chennault showed was that yes, the Zero is a better fighter than the P-40, but if you use the P-40s advantage in terms of speed, diving ability, and firepower and don’t turn with them, you can defeat them,” van der Linden said.

The AVG turned into a living laboratory for Chennault’s theories on defensive pursuit, which ran counter to the more prevalent offensive strategies centered on heavy bombers. Despite the success of the strategies, defensive pursuit wasn't readily embraced by military leaders back in the U.S.

“The rise of really fast and well-armed bombers in a world that had emerged from the First World War with a certain set of experiences and beliefs and so on, meant that the Second World War started with those beliefs being carried over,” said Doug Lantry, chief historian of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

“[There was] a real faith among many powerful leaders that these new fast bombers would always get through to the target and that they were invulnerable. And they just couldn’t be stopped,” Lantry said. “And so pursuit aviation was, in a lot of cases, just put on the back shelf and ignored.”

5. Let’s talk about that iconic aircraft nose art.

The Flying Tigers began with 100 P-40 aircraft supplied by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation's plant in Buffalo, New York.

“They had to be taken from the plant down to Brooklyn and put aboard ships,” Alyn said. “Three different ships sailed for Rangoon, Burma with 100 aircraft destined for the AVG.” Their arrival in the capital of what is now Myanmar took an ominous turn when a crane unloading a ship dropped one of the aircraft in the harbor, instantly reducing the fleet to 99 aircraft before operations began, he said.

The iconic shark’s mouth paint scheme came later. According to Alyn, the idea for the fierce face came after AVG pilots were visiting with friends and spotted a photo of an airplane painted in the scheme on the cover of Illustrated Weekly of India sitting on the coffee table. They took the idea back to Chennault, who gave them permission to do it.

“He liked it so much that he said he wanted all their aircraft painted that way,” Alyn said.

For today’s military, the legend of the bravery and effectiveness of the AVG underdogs endures.

“What they did show was that you need to be open-minded and ready to adapt to the circumstances. And Chennault was very smart in this, like, you take what you have–in this case a P-40–and you emphasize its strengths and minimize its weaknesses,” van der Linden said.

Then there was the role they played in lifting the spirits of the U.S. in the dark months following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“They were honestly no more than a pinprick in the side of the Japanese but let them know that they weren’t going to get away with it without some payback,” van der Linden said. “The real importance was for the folks back home.”

“They came together in a very cohesive and very effective flying force that served as the model for what we continued to do in China after their service was over,” Pfeifer said.

Mostly, the AVG was an opportunity for an aviator from rural Louisiana who dared to challenge established military thinking to be proven right, historians say.

“The bottom line is that over time [Chennault] was proved correct,” Lantry said. “He was proved correct that bombers needed long range escort. And he was proved correct that a wide and continuous early warning network was vital for pursuit aviation. And he was proved correct that operating as tactical teams instead of individuals yielded better results,” he said.

“Here’s a few people as volunteers who have shed rigid military authority in favor of this kind of informal adherence to a charismatic, but demanding teacher and leader. And the legend is that they really did more with less,” Lantry said. “They really achieved a lot in a short period of time, against really huge odds. They could not have been favored in that fight, and yet they came out of it winners.”

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox