How to Care for Your Lycoming Camshaft

Often called the Achilles heel of the Lycoming engine, here’s how to keep that camshaft doing what it should.

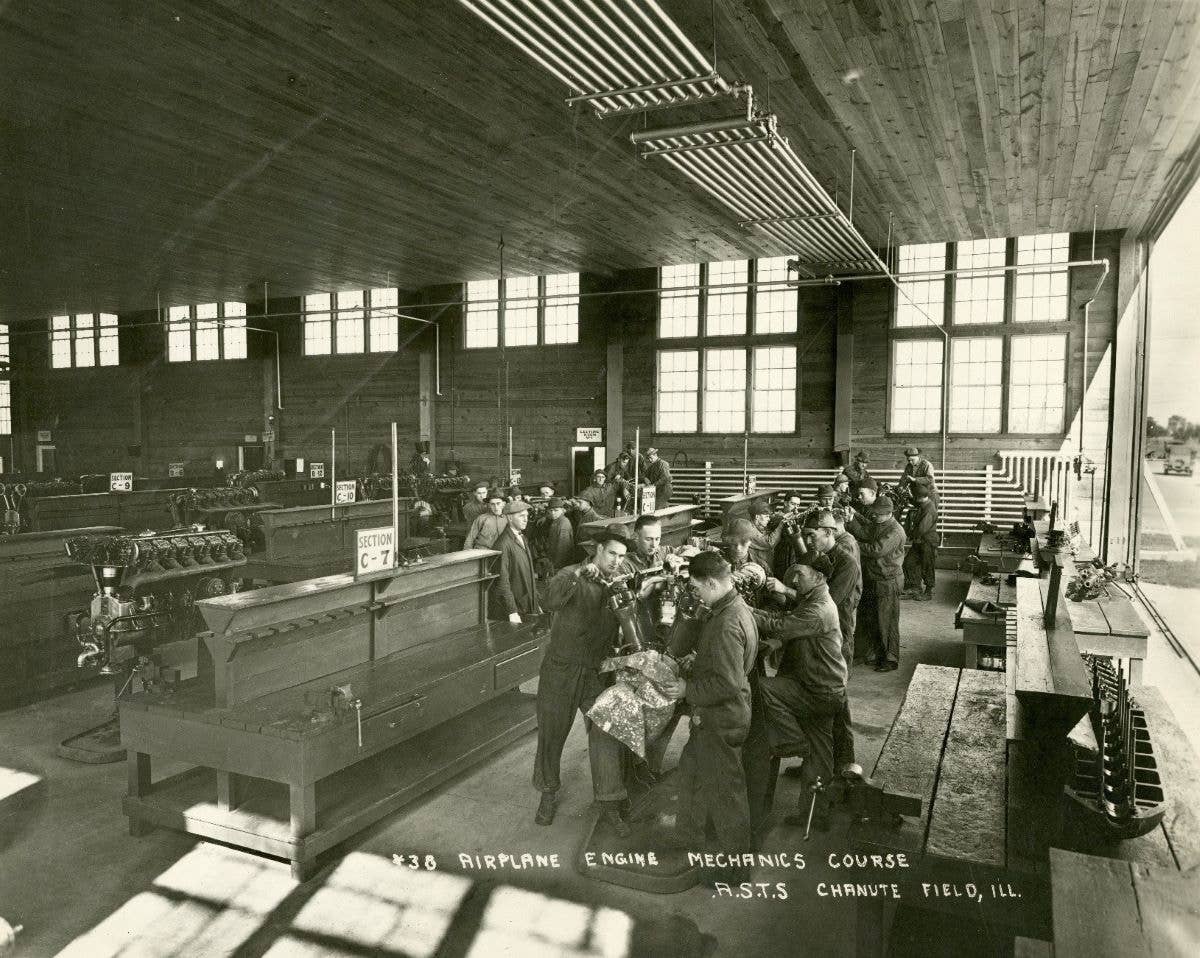

It is easy to look at the camshaft and tappet body using a flashlight and inspection mirror. [Photo: Richard Scarbrough]

You are making metal. I am sorry about that. Everyone needs to take a deep breath and back away from the screen for a minute. Better? OK, let’s try this again. If you know, you know.

If you don’t know what that means, consider yourself among the lucky few owner-operators who have not heard that term. Allow me to break it down for you. The phrase “making metal” occurs when someone finds tiny metal flakes in the oil, typically in the oil screen or oil filter. Do people even still use oil screens instead of a filter these days? Yes, and they are excellent at stopping rocks from flowing through your engine.

“If the buckle of Orion’s belt stays in place on the cloth, that means you are about to spend some money. If the metal leaps to the face of the magnet, you are about to spend a lot of money.”

The flakes you see are bad. Supposing the metal consists of aluminum, that is. If your engine makes ferrous metal, that is not bad—it’s terrible. Ferrous metal means rotating parts, and rotating parts equate to big dollars to replace.

How can you tell the difference? Get yourself a clean white lint-free cloth and lay it out on the workbench. Arrange the metal fragments in the shape of your favorite constellation and run a magnet over it. If the buckle of Orion’s belt stays in place on the cloth, that means you are about to spend some money. If the metal leaps to the face of the magnet, you are about to spend a lot of money.

Where to Look

Are the oil screen and filter the only place one can find this nefarious material? Great question, and the answer is a resounding no. The screen and filter are where the technical publications (TechPubs) will tell you to look for metal; however, there is another place.

I learned many valuable lessons during my stint owning an aircraft engine shop, one of which is how to tell if a camshaft or tappet body is going bad by inspecting a piston from the cylinder—specifically the piston skirt. Many of these tactics are not found in any TechPub.

Each time a customer would drop off a cylinder, one of the technicians would eagerly slide the piston out of the cylinder and hold it up for inspection. Should the piston skirt reveal embedded bits of shiny metal flakes, a request to look at the camshaft followed. It is easy to look at the camshaft and tappet body using a flashlight and inspection mirror. I shot the lead photograph for this article during an inspection. What greets the owner is either a sigh of relief or a sinking feeling in the gut. Your motor is coming down, and we need to split the crankcase.

The Camshaft Foundation

Textron Lycoming Engines designs and manufactures aircraft powerplants, parts, and accessories and has been doing so for as long as anyone can remember. From its headquarters in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, Lycoming manages a network of independent distributors that sell everything from a simple gasket to the massive IO-720 aircraft powerplant.

Long known for reliable and high-performing engines, there has long been an industry perception that the camshaft was the Achilles heel of the Lycoming engine. That analogy, warranted or not, dogged the engine maker through the past few decades. While Continental Motors share their number of camshaft issues, we’re sticking to the Lycoming motors in this article.

One key point is that a good number of people point to the camshaft’s position to explain the troubles Lycoming faces. In Lycoming engines, the camshaft is above the crankshaft just under the backbone. Here, it does not receive the benefit of gravity-fed oil distribution. Some shops have a procedure called “cut oil groove” (COG), in which a hacksaw blade makes a small slit near the camshaft to allow greater oil flow. I may or may not know anything about that.

Aircraft OEMs are constantly receiving their TechPubs, sometimes for airworthiness issues, others for economic ones. One such shift in policy is Lycoming Special Service Publication No. SSP-567, which recommends using only new camshafts and tappet bodies as opposed to recertifying continued time material through grinding. Does Lycoming wish to address cam and tappet body concerns, or do they want to sell new material? One wonders. This author’s opinion: most likely a little of both.

It is an infrequent occurrence when OEMs update their component maintenance manuals (CMMs) or illustrated parts catalogs (IPCs). They chose to issue stand-alone documents instead. Service Instruction (SI) No. 1011N includes replacement part numbers, part supersedes, inspection and replacement guidelines for tappets, hydraulic lifter assemblies, and hydraulic plungers on Lycoming Engines.

Frequently, an OEM will use an instruction to introduce or update a new part style. SI No. 1514D, for example, is a roller tappet part information update.

Another instruction, SI No. 1543, is a notification that tappet part number (P/N) 15B26262 is now an approved replacement for tappet P/N 15B26064.

Not all service instructions are strictly informational, and others are structural. Service Instruction No. 1424A provides the installation procedure for P/N 15B26066, hydraulic tappet/plunger assemblies.

Cause for Concern

As stated many times in this column, if you have questions about maintaining your aircraft, remove speculation and consult with a maintenance provider you can trust and build a relationship if you haven’t already. Someone like JD Kuti of Pinnacle Engines in Alabama, who has been in the engine business for over 15 years. He has experienced his share of camshaft and tappet body failures.

JD and I recently sat down to discuss the finer points of aircraft engine maintenance, precisely the Lycoming camshaft issue.

FLYING: Are Lycoming camshaft and tappet bodies failing at a higher rate now?

JD: We have seen quite a few camshaft failures recently; however, I believe that is due to increased COVID-19-generated aviation activity. More people than ever [are buying] small aircraft, and some of these planes have not flown in years. When an aircraft sits, it deteriorates rapidly.

Some symptoms of a potential issue are:

- Metal found in the filter

- Oil analysis showing high metal content that came on suddenly

- Decreased in performance, impacted most on the climb out on a hot day

FLYING: Does Pinnacle run new or overhauled camshafts and tappet bodies?

JD: At Pinnacle, all of our estimates include a new camshaft and tappet bodies. Some clients wish to overhaul their current components, primarily if they are first run and have shown good performance. Others go the recertified route to save a few bucks.

FLYING: What are the root causes of the tappet body spawling and camshaft lobe wear?

JD: The number one cause of these failures is inactivity. Aircraft are supposed to fly, not sit. This behavior introduces corrosion, which can worsen depending on the operating environment and climate. I also want to re-address number one; don’t just leave the aircraft dormant and then crank it over once a month and let it run for 15 minutes. You are doing more harm than good.

FLYING: How can owners prevent this?

JD: Fly your airplane. I cannot stress it enough. If you cannot fly for one hour or more, leave it parked and preserve it for long-term storage. Also, change your oil every 25 hours and your oil filter every 50 hours. Always cut your filters and inspect the elements for metal and debris. The reason for skipping [a cycle] is to allow the metal to accumulate enough to spot it.

FLYING: Does Pinnacle recommend any additives or aftermarket cam products?

JD: That is a very personal decision. We don’t have the data to support it. I know the products you are referring to, so we recommend that customers reach out to each company individually and make their own decision.

We will advise customers to use one product here, Mororstor. At one time, it was recommended by Continental for long-term storage. You spray through the spark plug orifice and fogs the cylinder wall. After applying to each cylinder, empty the remaining contents of the can into the crankcase.

Lycoming acknowledges that camshafts and tappet bodies are prone to fail. The fact that they will spend research and development dollars on improving the situation is hopeful.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox