How the Folks Who Build Airplanes Take Care of the Environment

There are many ways that they do it, and we share ways you can do it, too.

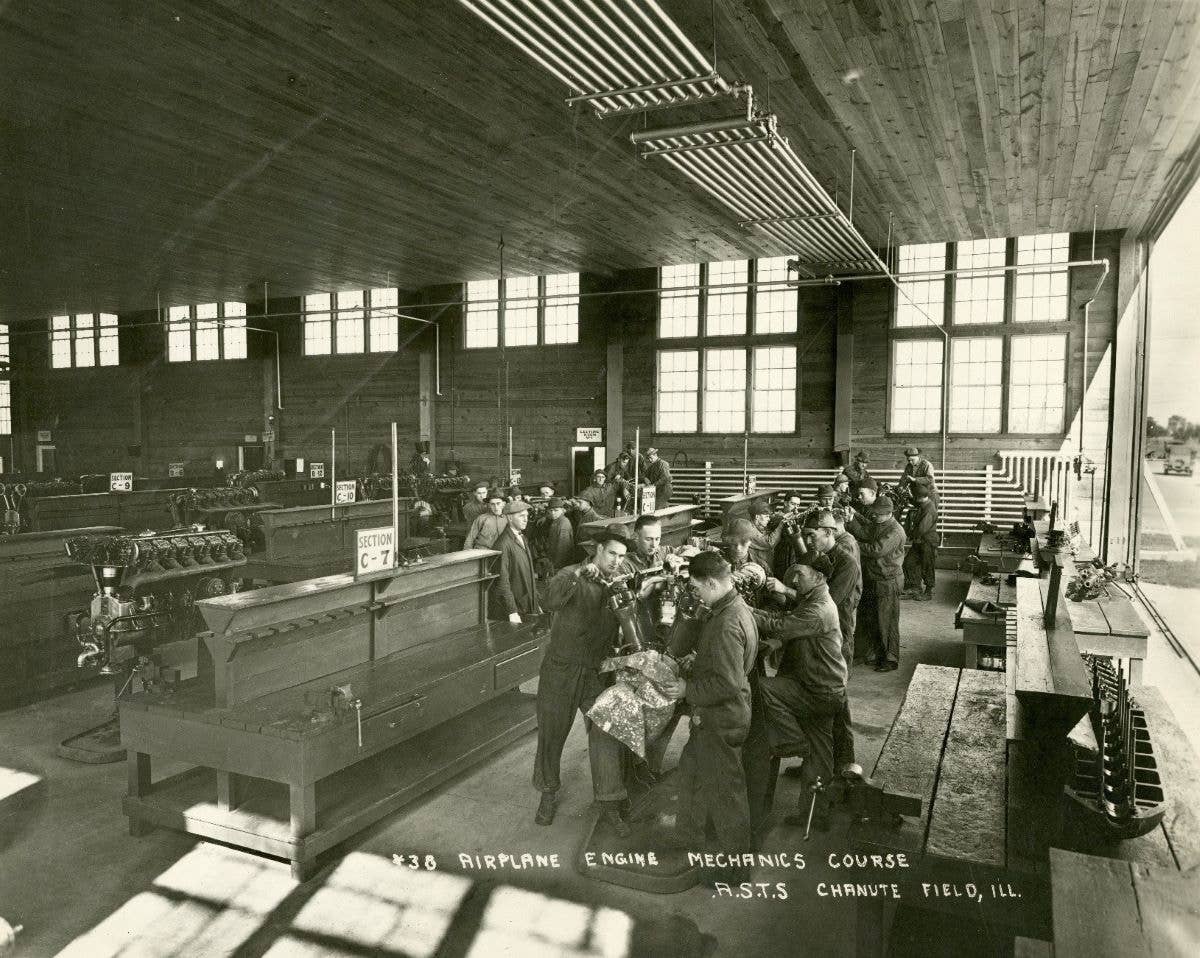

For all the talk of aviation being harmful to the environment, there’s a lot that the industry does to help it. [File photo: Adobe Stock]

“Airplanes are bad for the environment.” Have you heard that? Some headlines scream it from the virtual mountain tops on the internet, intending to make us question our desire to fly, thereby contributing to total environmental destruction.

Can you guess what else is bad for the environment? Just about everything else.

Popular culture uses media to influence; that is no secret. We are all in the advertising business.

From the earliest cave art depicting Thorg’s champion takedown of the mighty mastodon to your second cousin Lunar showing off her new thrift haul, people have engaged in social storytelling to influence the thoughts of their audience.

It began with cave art, then traveling minstrels, and finally the tsunami that is social media. Every group with an internet connection will voice their opinion and subsequently find an audience to hit the like and follow button, present company included.

But the question remains: Why would we fly if it is terrible for the planet?

Considering other modes of transportation, is air travel that awful for the planet? See below for some data points to consider when researching this answer.

Friday is Earth Day, and across the globe, people will gather to come up with new and innovative ways to celebrate Mother Earth. In honor of this annual event, I propose we put aviation on the environmental stage, not to criticize, but to highlight all the good that flying airplanes does for the Earth, and the steps we collectively make to continue the evolution to a more sustainable industry.

Innovations

Former U.S. Secretary of Transportation Andrew Card once famously remarked, “Don’t believe everything you read in the newspapers.” I suppose we can update this to include the internet as well. The truth is that the aerospace community is making great strides to become more environmentally sustainable. As simple as that may sound, we cannot just issue a mandate and then sweep it into change with a broad brushstroke.

When Ford Motor Company decided to make its iconic F-150 pickup truck lighter to comply with federal fuel consumption standards, it used aluminum in the construction. FoMoCo shaved 700 pounds and did it from the more lightweight material and paired that with a smaller engine dubbed the Ecoboost.

As you may recall from my FLYING article on the sunsetting of 100LL, it took GAMI 11 years of development to finally win approval by the FAA, and perhaps more time will pass before unleaded avgas is fully adopted—though that timeline will likely be accelerated.

By comparison, when Boeing decided to update the construction materials for the 787 Dreamliner, it took a full nine years from design to its first commercial flight with passengers in 2011. That is an eternity in the automotive world.

The movement toward unleaded aviation fuel is undeniably a positive step in the evolution of air travel. Fuel is not the only innovation currently in work in the aerospace sector. FLYING’s editor-in-chief Julie Boatman recently published a piece on the experience of her first flight in an electric-powered airplane.

Initiatives

The commercial industry consistently rises to the challenge when demand surges for a new supply offering. This new demand drives innovation. Companies like GAMI and Pipistrel are changing the way we fuel and power aircraft. Although full deployment is still several years away, actions are now in place to move closer to an environmentally sustainable industry.

The FAA is also involved in the movement. Its efforts to build a net-zero sustainable aviation system by 2050 range in everything from aviation fuel to technology, flight operations, airports, etc. The Climate Action Plan initiative is one way the FAA hopes to operate more sustainably.

Embracing the environment headlines the July/August 2021 FAA Safety Briefing. One point to consider is something the FAA refers to as the “darker side of going green.” Electric power is in vogue currently, and yes, electric energy is cleaner than burning fossil fuels. However, it is not entirely blameless either.

Batteries make up a bulk of the mobility power, batteries containing specific minerals that are sometimes mined using destructive collection tactics like strip mining and mountaintop removal. Additionally, the regions containing these precious resources can frequently be in conflict zones or behind oppressive regimes.

Practices

During my tenure at the engine shop, we were always mindful of our maintenance practices, waste, and shop products. While everyone wants to be as environmentally sustainable as possible, it is impossible to achieve perfection. Every company leaves a footprint. The goal is to minimize said impact. I will say that the reciprocating engine overhaul business ran on razor-thin margins, and I did everything to reduce, reuse, and recycle.

We stripped engines during teardown, and everything went into a container with the engine information placarded on the outside. We retained these engine remnants outside the repair station footprint in a storage container. We did our best to use this material whenever the work would allow it. I will get into all of that when we discuss engine maintenance.

The number one rule in engine maintenance is cleanliness, and to list all of the reasons why would take up the balance of this article. The bottom line is that you cannot inspect what you cannot see. When steel parts enter the inspection arena, they need to be free of contaminants. Cleanliness is critical when performing magnetic particle inspection (MPI), the tiniest bit of grease will contaminate the entire bath solution.

Mineral spirits, the degreaser of choice for years, worked well and cleaned engine parts down to the tiniest grease spot. When I bought the shop, it was the only method of degreasing. My Zep rep Ed said he had a better way.

Enter the Zep Big Orange Liquid Citrus Solvent Degreaser. According to the website, this product is an organic, non-petroleum-based cleaner, degreaser, and deodorizer. Zep advertises that this product offers comparable degreasing power to petroleum distillates and chlorinated solvents.

We used Zep Big Orange in parallel with mineral spirits and found both to work well. Why did we retain the old ways? That is an age-old tale that deserves its article after the statute of limitations expires.

Another way aircraft mechanics can do their part is to enact a shop towel recycling program.

I recently sat down with Steve Simpson of Closed Loop Recycling to discuss the benefits of reusable shop towels, absorption pads, and personal protection equipment (PPE).

Q: Explain the closed loop process for the aviation industry.

A: Our recycling process takes your used absorbents, PPE, and dirty storage drums back to our facility to clean them for recycling and reuse.

Q: How can partnering with Closed Loop Recycling benefit the environment?

A: We have a mantra at CLP: “Whatever it takes.” The bottom line is that partnering with us will turn three waste streams into three reusable products:

- used oil

- absorbents and PPE

- collection drums

Q: What can aircraft maintenance professionals do in their daily work to minimize their environmental impact?

- Reduce consumption first and foremost. Try to use one instead of two—it’s that simple.

- Reuse materials such as absorption pads, gloves, aprons, caps, and PPE instead of throwing away disposable products.

- Recycle any leftovers that remain.

Back to the question from the top of the page. Is air travel terrible for the environment? A most excellent question indeed, and hotly debated in the media, on Capitol Hill, and around the water cooler at the office. Before you answer, please consider these quick data points.

When heeding the advice of Steve from Closed Loop, he offered the absolute best way to operate sustainably is to reduce. The best way to minimize the need for new material is to maintain existing material.

That said, you may be surprised to learn that the average age of automobiles in the United States was 12.1 years in 2021. The average age of general aviation aircraft is 30 years, and a sizable portion is over 40 years old. Maintain what you have, and you do not have to expend resources to produce new. The last graphic I will leave you with is the number of scheduled passengers boarded by the global airline industry from 2004 to 2021.

Not all of those passengers represented above would have traveled by automobile had they not flown. But safe to say that a significant number would have. Does that look green to you?

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox