Could a Bunch of Junk Derail U.S. Activities in Space?

NASA, the Defense Department and U.S. Space Force all have big plans—and a potentially bigger obstacle.

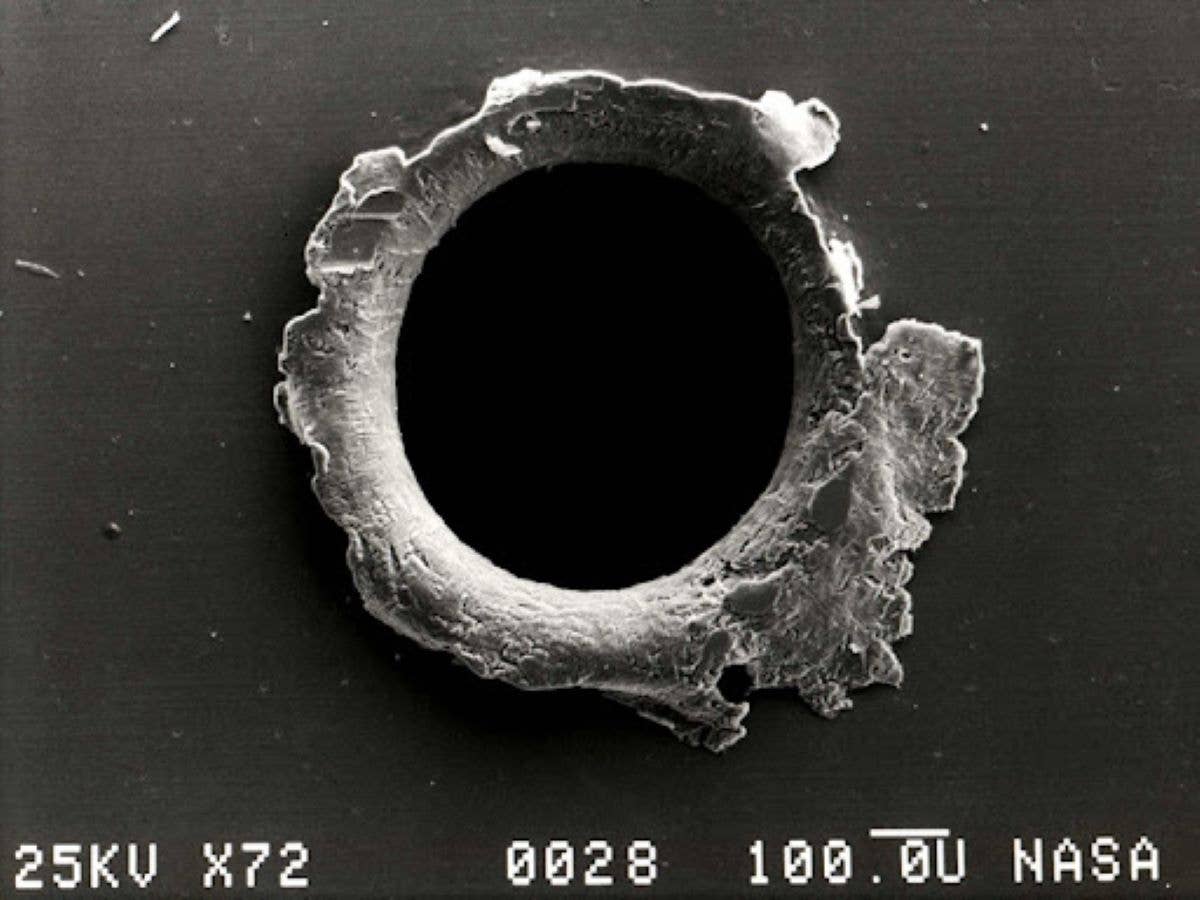

What looks like a bullet hole in the panel of NASA’s Solar Max satellite was actually created by an impact with space junk. [Credit: NASA]

Space junk, or orbital debris left by humans in space, including satellite fragments, is a problem.

Currently, Earth’s orbit contains hundreds of millions, and by some estimates, trillions of pieces of debris—see for yourself. The vast majority of these are tiny and pose no threat. But a speck of debris just 10 centimeters in diameter can cause significant damage to spacecraft, and there are at least 36,000 objects that fit that description.

When you add the threat of asteroids and comets (also referred to as near-Earth objects, or NEOs) to the conversation, things get even more dicey for agencies like the Department of Defense and the U.S. Space Force.

On Wednesday, the DOD launched a new “effort” to foster collaboration between the off-Earth commercial and defense sectors, building on the Commercial Integration Office it established earlier this month and the Commercial Integration Strategy it introduced in January. The Space Force, meanwhile, has hinted at adding offensive capabilities in space by 2026.

Both plans promise a future where the U.S. establishes itself as the top dog in outer space. But without a plan to address the growing debris field orbiting the planet, those efforts are likely to face major hitches.

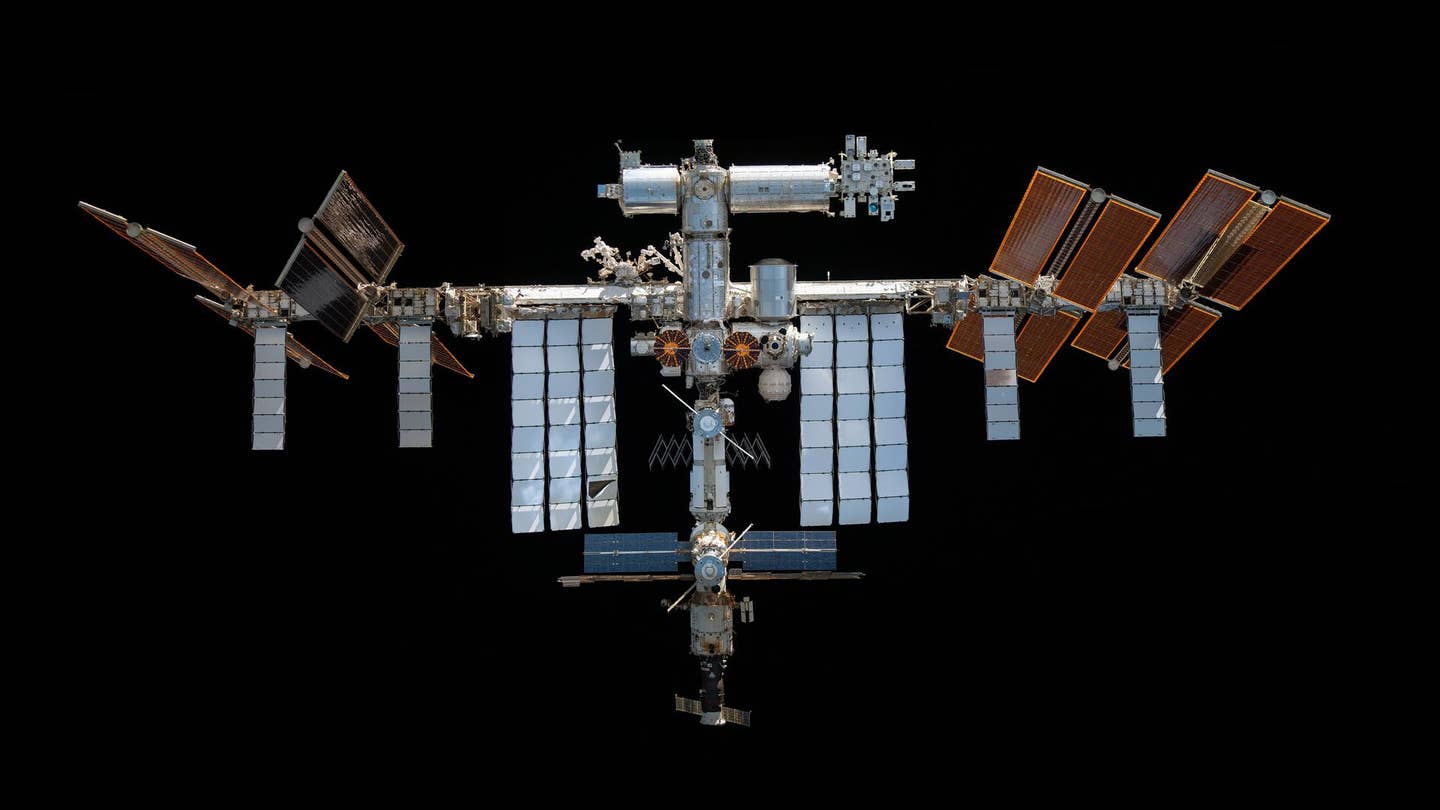

Take, for example, a near-miss that occurred in 2021. When a Russian anti-satellite test destroyed the country's Cosmos 1408 satellite and sent 1,500 pieces of trackable debris on a collision course with the International Space Station (ISS), crew members were forced to seek shelter— and the spacecraft narrowly dodged the debris field. Other spacecraft haven’t fared as well.

Had evasive maneuvers not been taken by the ISS, the incident could have ended in calamity. And it didn’t even take place where the majority of collisions and near-collisions do—en route to orbit, where tens of thousands of satellites circle the globe at lower altitudes.

According to experts, space is only going to get more crowded. Per consultancy McKinsey and Company, there could be close to 70,000 satellites added to Earth’s orbit if plans from companies like SpaceX come to fruition. Already, the firm has more than 1,600 Starlink satellites in space, with plans to launch tens of thousands more.

If that happens, the problem could escalate exponentially. Each year, there are dozens of near-collisions between active satellites and space junk, and the more spacecraft that enter orbit, the likelier it is that a crash will occur—which creates even more debris.

The U.S. has taken some steps to address the issue. In September, the Federal Communications Commission limited new satellites to a five-year lifetime, a measure that would reduce crowding in orbit. The agency earlier this month created a Space Bureau that will propose new “satellite and orbital debris rules.”

Meanwhile, a collection of other agencies and startups in the U.S. and abroad are attempting to remove debris and deorbit satellites with robotic spacecraft. But it could all be for naught – a study by NASA’s Office of Technology, Policy and Strategy found that rather than removing debris, it would be exponentially cheaper to build technology that allows spacecraft to avoid it.

However, the agency is hoping to wrangle the NEO problem before it gets out of hand. On Wednesday, NASA presented its strategy for planetary defense, a response to the White House’s updated National Preparedness Strategy and Action Plan for Near-Earth Object Hazards and Planetary Defense released earlier in the month.

While the strategy is designed to protect the Earth itself from impact, it calls for measures like enhanced tracking of NEOs, which could mitigate the chance of an orbital collision. It also describes tactics to predict the paths of asteroids and comets and communicate potential hazards quickly.

But even if NASA and other agencies are able to prevent NEO collisions, the problem of space junk remains. And by some estimations, we’re nearing the point of no return.

Kessler Syndrome was first introduced by researcher Donald Kessler in 1978. Kessler proposed a hypothetical scenario wherein one large collision—like the near-miss between the ISS and Russian satellite debris—results in a cascade of smaller impacts, rendering Earth’s orbit inescapable due to debris. The inactive but still-orbiting Envisat satellite may represent another potential trigger.

Kessler also hypothesized that such an event would become inevitable if we reach a critical mass of objects in low-Earth orbit. In other words, if humans continue to launch satellites while leaving defunct spacecraft in orbit, cascading crashes could sideline future space activities.

With all of that being said, we haven’t quite reached that point, and we may never. Initiatives like the FCC’s could remove a sufficient number of satellites, with an array of agencies and startups pitching in to remove other junk.

But if stakeholders tend to agree with NASA’s assessment—that avoiding space junk is cheaper than removing it—countries like the U.S. will need to put incentives in place to clean up Earth’s orbit and avoid a Kessler disaster.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox