Buyer Beware

An instructor is left with unsettling doubts about a student’s motives.

[Credit: Joel Kimmel]

In the early ’90s, a friend and I bought a Kitfox. It had a Rotax engine specifically made for airplanes. The worst mechanical event during our ownership was when the exhaust came loose in flight, filling the cockpit with noise and smoke.

Our kids grew up with this little airplane, and we flew all the time with the doors off, with them sticking their heads out into the slipstream for a better view. When a friend put his Cub on floats up for sale, we decided to purchase it. We sold the Kitfox to a friend who owned a powersports business, and that was the end of the Kitfox for me until late Summer 2002. The new owner of the Kitfox then wanted to sell the airplane. The buyer, a student pilot, needed tailwheel instruction, and I agreed to spend some time training him. I did not find out until our first lesson that the student had 55 hours of instruction and had yet to solo. This can be a red flag and may indicate someone is better off trying something besides flying. Because he was the new proud owner of the Kitfox, I agreed to give it a go.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowAfter two lessons in non-ideal weather conditions, the student had yet to make a landing where I did not have to intervene. On wheels, this lightweight airplane could be a handful for someone of my experience, let alone a newbie. I told our friend it was a lost cause. He asked me to take the student up on a calm evening; if he could not manage landings, then I could call it quits. OK, deal! October 2 featured perfect low-wind conditions, so we met around 5 p.m. to practice landings. There was a light wind out of the northeast so we used Coldwater Airport’s smaller 3,500-foot Runway 3 (now 4). The landings were not going well, but the takeoffs started to get smoother. Around his fourth try, he landed without bouncing horribly and with zero input from me, and then made two more landings without help. As we climbed after the sixth landing, out of the blue he asked, “If the engine quit right now, what would you do?”

I explained that at low altitude, all you can do is pick the best spot straight ahead and push the nose down to keep the speed up for a glide and hope for the best. He nodded, indicating he got the concept. He lined up with the runway and executed his best landing yet. I said, “Wow, nice job,” as we rolled to a stop and took off again.

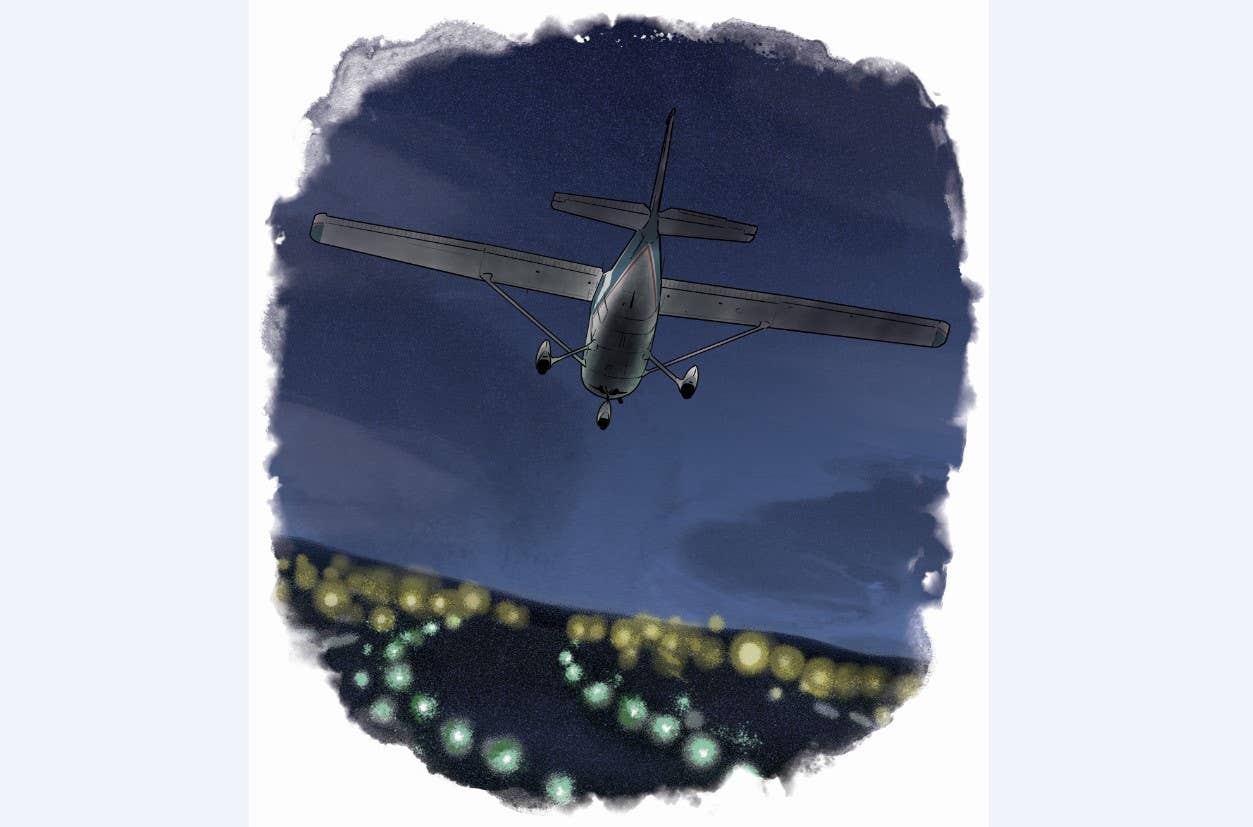

I was finally feeling as though I no longer had to watch his every move. I was enjoying a view of the lake off to our right when, at around 200 feet, the engine went silent. It did not sputter like an engine starved for fuel or kick like it had a spark problem. One second it was running at full power and the next, it was completely dead.

Training kicked in, and I immediately took the controls with no resistance on my student’s part. I shoved the nose down hard because in a climb at a low airspeed, most of the airplane’s momentum is coming from the engine. Without it, I had to use our altitude for airspeed. Once in the glide, the windshield filled with power lines, a busy two-lane highway, and a bowling alley.

What I saw did not look survivable, so I did what we are trained not to do: I turned the airplane, but not by lowering a wing and banking. I somehow got the idea to push the left rudder and skid the airplane 90 degrees to the west of the runway.

The windshield filled with an unobstructed grassfield, but as comforting as that was, the maneuver had used up most of our precious momentum. The airplane was now in a nose-low, wings-level, minimum-speed descent. As the ground rushed up, I pulled back to raise the nose, but not much happened. The airplane hit with an awful crunching sound, and within a few feet, flipped inverted. As the g-forces of the sudden deceleration hit us, we were thrown against our shoulder harnesses, but they kept our faces off the instrument panel.

I asked my student if he was injured. “I don’t think so.” I told him to evacuate the airplane because of fire risk. We had been flying with the doors locked up and open, so there was no mangled metal in the way of our exit. We released our belts and fell to the ceiling, then rolled out onto the wing. From there, we stood up and ran. We could hear sirens in the distance because traffic on the road saw what happened, and many motorists were stopped and running in our direction. Someone had already called 911. After a few minutes with no fire, my student noticed the strobe lights were still flashing. He asked if he should turn the master power switch off. Smelling no gas, I told him to go ahead.

The next morning at the airport, two FAA inspectors reviewed my credentials and one asked if I knew the survivability statistics of engine failure accidents on takeoff. I said, “Not very good.” He said so many were fatal, with pilot error being a big factor. He added since I was there talking to him, he wasn’t going to question whether my actions were correct. Since I was still alive, that was proof enough what I did worked. He said, “Let’s go find out what caused the engine to quit.”

There was fuel in the carburetor and ignition on all the cylinders, and the compressions were good, so we tried the starter. Within one blade rotation, the engine came to life. The conclusion? Engine failure from an undetermined reason.

Did you catch two unusual things that happened? The first was the student asking about engine failure procedures right before an actual engine failure. The second was that the engine went from full power to nothing at the worst possible altitude. The Kitfox’s engine has two ignition systems for safety and two spark plugs per cylinder. If one dies, you still have a redundant system to keep the engine running. Two toggle switches by the student’s left knee controlled the two ignition systems.

Several months after the accident, we discovered the student’s life was a bit of a mess. He had lots of debt, troubled relationships, and a huge life insurance policy which specified he was covered under pilot training. Had I not been onboard, his chances of survival would have been close to zero. The question remains in my mind whether he’d planned it that way.

This column was originally published in the February 2023 Issue 934 of FLYING.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox